Basic HTML Version

98

|

WINTER 2012

IMAGING

//

S H O O T E R

A

s readers of Alert Diver

know, underwater

photography is an

equipment-intensive

business. It requires most of the

same gear land photographers use

plus much, much more. Cameras

must be placed in underwater

housings, and special strobes, strobe

arms, cords, housing ports and

extension rings are needed as well.

Add to that cases full of lenses and

all the diving gear — wetsuits of

varying thicknesses, drysuits, masks,

snorkels, fins, regulators, BCDs

and more. Because I often work in

remote locations where I cannot

buy specialized items I might need

or even get equipment repaired, I

must bring backups of everything

plus an assortment of tools. In total,

I often head off on assignment with

30 cases of equipment in tow.

On many assignments I bring an

array of supplemental lights, including

movie lights with hundreds of feet of

cable to be powered by generators

on boats above. I sometimes envy

my street-shooting colleagues (who

travel with only two or three camera

bodies and a handful of lenses) and

underwater-photo enthusiasts who

get to travel to beautifully exotic

destinations with minimal baggage.

But then again, they don’t get to spend

months with sharks or sea turtles.

I have often mused that being

a National Geographic magazine

photographer is not unlike being

a professional athlete in that you

are only as good as your last game

(or in my case, my last story). The

magazine expects results, and a

photographer cannot have failures

and continue to expect assignments.

There are so many things that must

go right for success, and some

things inevitably go wrong. Learning

to overcome problems is key, and

problems come in all shapes and

sizes — from luggage not arriving

to equipment malfunctions. Mother

Nature can always be relied on to

bring variables you simply can’t

control, including bad weather, poor

visibility and the animals you’re

there to shoot just not showing up.

Knowing there are so many things

I cannot control, I dedicate as much

time as possible working on the

things I can. Detailed research is

crucial, because I need to know as

much as possible about my subjects

and locations. I want to know where

and when they can be found, if the

water is clear enough for pictures

and what behaviors I might be

able to document. Once I have the

assignment, I adopt a mindset in

which failure is not an option. This

job has been called a zero-mistake

game: Fail to deliver the goods, and

you are done. With this always in

mind, I have learned to become good

at research and solving problems.

Perhaps the most valuable

resource I have, though, is time in

the field. With time I can usually

overcome whatever challenges or

problems occur. Time allows me to

learn firsthand about the place in

which I am working: what happens

at different times of day and how

animals behave. Often the best

images are made when something

unexpected happens, and taking time

allows more opportunities to present

themselves. But serendipity can

be seized only if I am prepared, so

while I might be wandering casually

through un derwater domains, I am

always vigilant and ready.

Brian Skerry:

On Being a ShOOter

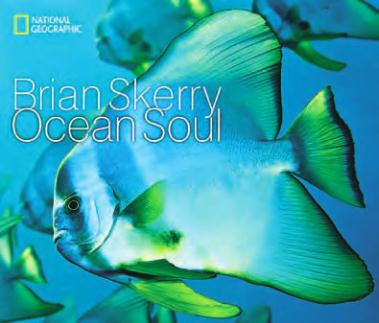

Above: Cover of Ocean Soul

Below, from top: A fisherman holds the shrimp he caught

in his bottom trawl net after towing it for an hour; the other

dead animals are bycatch, thrown back into the sea as

trash. Loligo opalescens squid spawning off California’s

Channel Islands. The male’s arms blush red when embracing

the female, a warning sign to competing males to back

off. Yellowfin tuna in a tuna ranching operation off Baja,

Mexico.

92-99_Shooter_Winter2012.indd 98

12/27/11