|

103

were overly monochromatic without strobe, I felt that

shooting available light was the best solution.

However, with the humpback whales in Tonga I

sometimes found the strobe to be an advantage. The

whales had brilliant white coloration on their sides,

and the strobe helped with contrast, particularly

with deep or backlit animals. The task was to find

a strobe small enough yet powerful enough to do

the job. Typically I would work at quarter power

so I had a rapid recycle that could keep up with my

motordrive for bursts of 10 frames per second, but

to be effective that required proximity to the whale.

The whale largely controlled that, and a friendly whale

might benefit from strobe lighting. This is another

risk/reward scenario: If the whale is too far away, the

strobe will offer no optical benefit and will contribute

water resistance. Bulky, buoyant strobe arms used

to minimize wrist fatigue while scuba diving are the

wrong solution for freedive photography because of

their negative impact on hydrodynamics.

SHALLOW WATER SEASCAPES

AND OVER/UNDERS

In much of the available-light work I do while

freediving I find that bracketing with strobe power

and shutter speed (like I might do on scuba) isn’t

particularly productive. In high ambient light at the

surface it is sometimes hard to see the LED numbers

that show camera settings and meter reading, and

things happen so quickly on a single breath of air that a

bit of camera automation is a relief. For this I find that

the automatic setting in shutter-speed priority serves

me well. I might dial in a bit of exposure compensation

if my subjects are coming out consistently over- or

underexposed. Even with strobe light I find this

generally works quite well as my strobe power is set so

low (to achieve rapid recycle) that it rarely overpowers

the aperture required for the chosen shutter speed. If I

bracket at all, it is likely with strobe power.

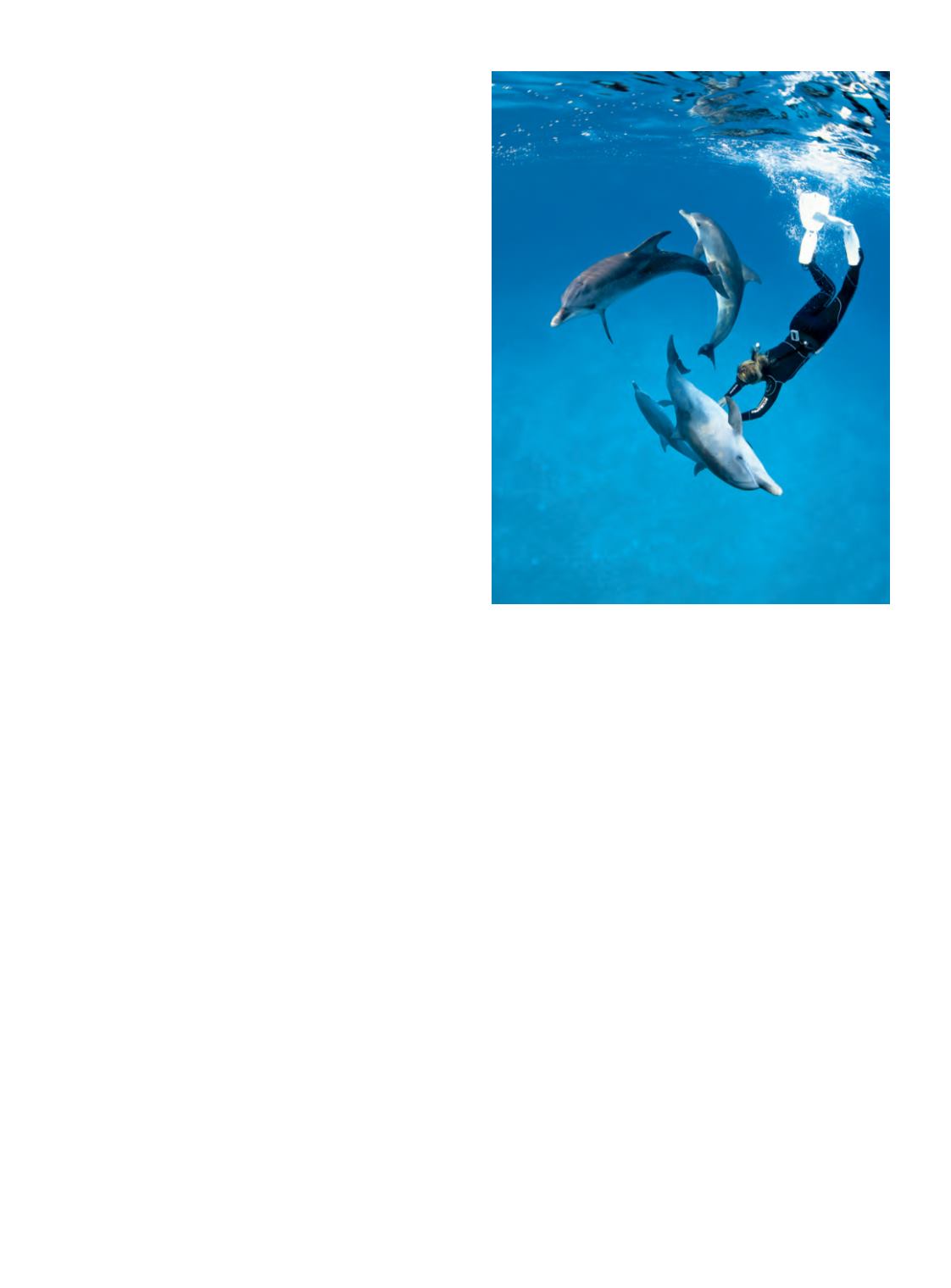

I had an issue with this protocol recently, however,

while shooting snorkelers with spotted dolphins in the

Bahamas. In the late afternoon, shooting with a shutter

speed of 1/160 second to stop the action gave me an

aperture of about f/8 for the ambient light. Working at

25 percent power on the strobe and ISO 320 gave me

consistently good exposures. But as it got closer to dusk,

the ambient light dropped and required f/4. Depth of

field suffered, and the strobe would often overpower the

foreground subject (typically the dolphin). My solution

was to kick up the ISO to 640 and cut the strobe power

to 12 percent, which brought the apertures back to f/5.6

or f/8 and provided exposures appropriate for marine

life two to three feet away.

With over/unders or shallow coral-reef photography,

shutter-speed priority with the sun to your back is

generally a reliable way to shoot. If I want more color

on a foreground subject or to light the inside of a

model’s mask, I will add a strobe to the toolkit.

A FINAL TIP

There is nothing worse than freediving into a once-in-

a-lifetime marine-life encounter and taking a few shots

only to have your data buffer load up. It won’t take

many instances of feeling like your lungs are bursting

while you wait for the buffer to clear so you can shoot

just a few more frames before you figure out that the

$20 secure digital card you bought at Office Depot is

not the right tool for the job. You’ll want the fastest and

most efficient media you can buy.

With freedive photography you need to put it all

together: mental and physical fitness, streamlined photo

equipment, hydrodynamic water wear, optimal photo

technique and a beautiful shallow reef or some other

propitious environment for encountering significant

marine life.

AD

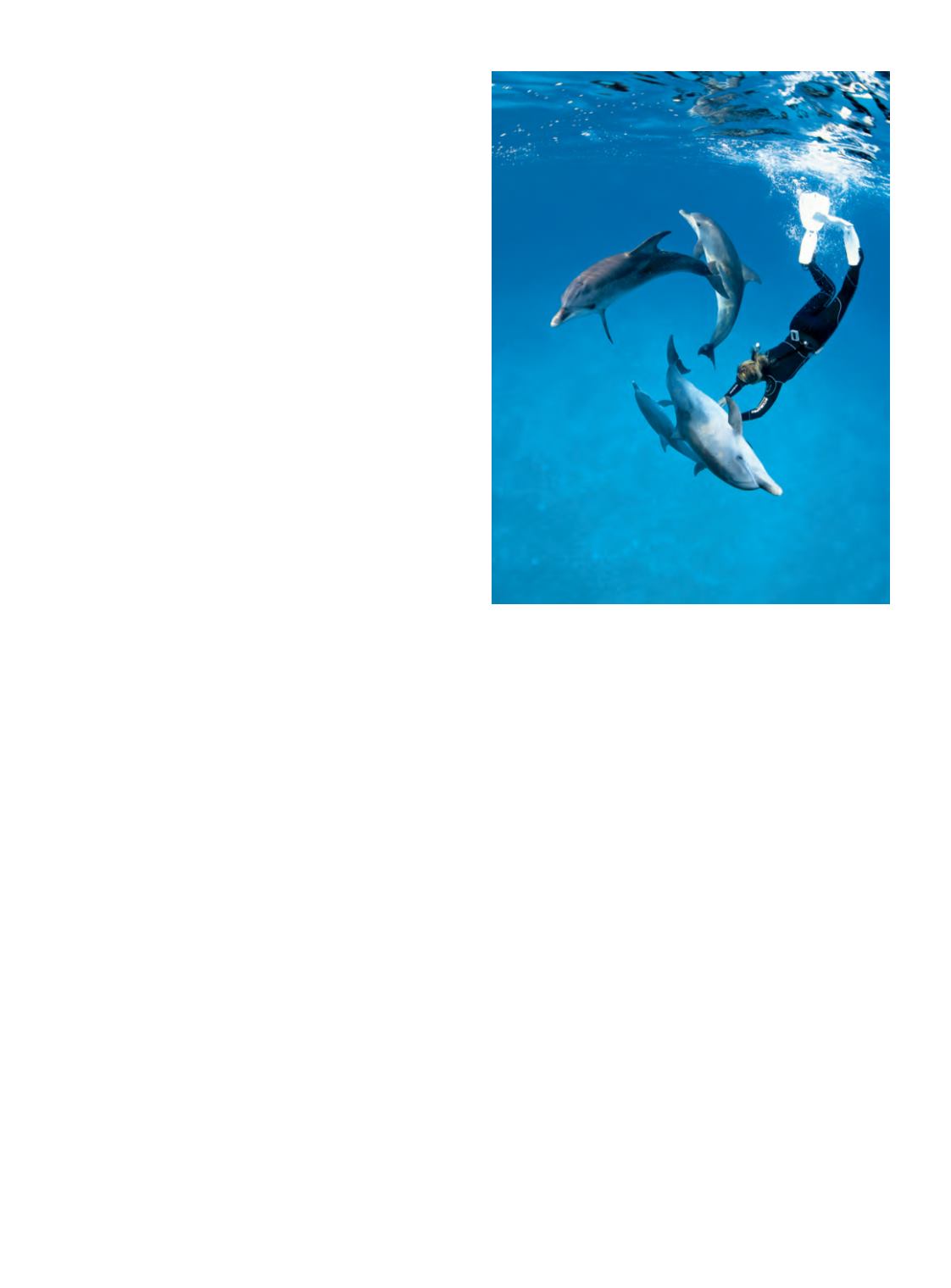

With marine life that moves very quickly, like these spotted

dolphins off Bimini, a strobe that recycles very rapidly is an

advantage.

STEPHEN FRINK