longer as unique as it was when I took

it. It was the grand-prize winner in

the 2004 Veolia Environment Wildlife

Photographer of the Year (WPOTY)

competition, sponsored by the Natural

History Museum in London and BBC

Worldwide. It was also the first photo

from a digital camera to win any award

in that competition. I would be surprised

if any images shot on film even made it

to the finals this year. I sank more than

$20,000 (which would be a lot more

in today’s dollars) into that sardine

run self-assignment over a three-year

period with long odds of earning any of

it back. Thanks largely to the publicity

fromWPOTY, I actually did recoup my

investment on that project. Not all my

expeditions have fared so well.

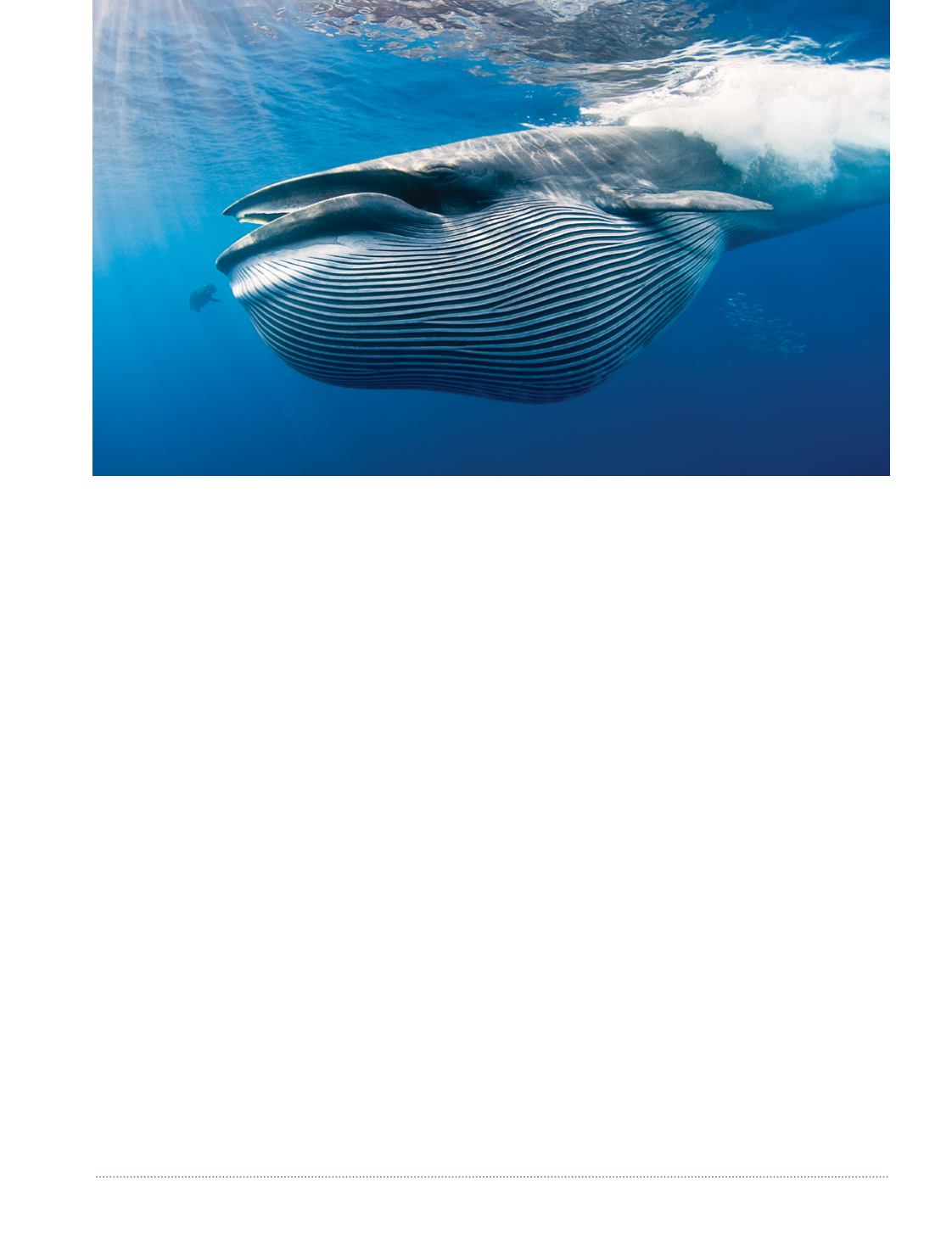

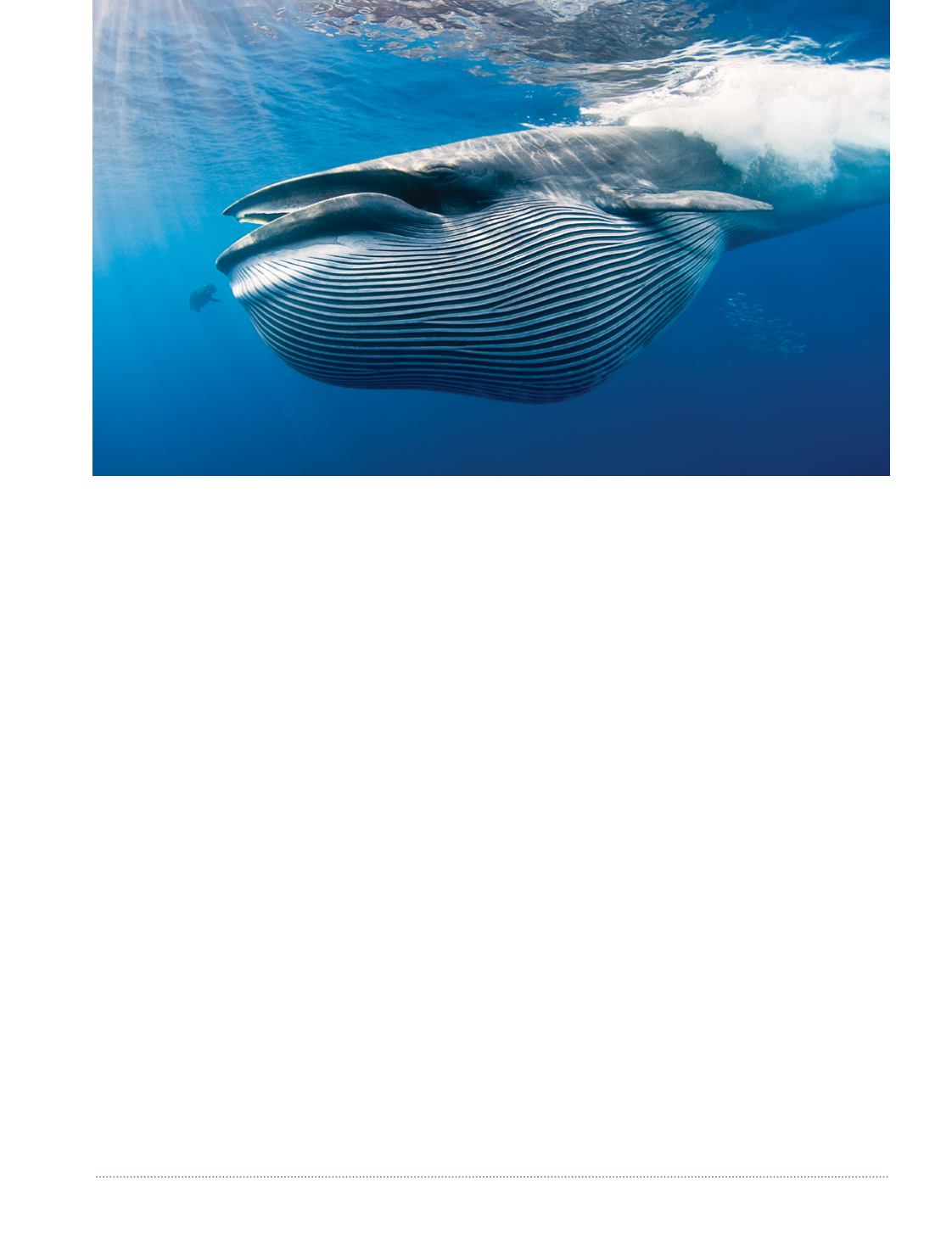

Another shot that earned back its cost,

which you may find hard to believe, is a

shot of a blue whale pooping. It expelled

a massive cloud of processed red krill,

and I took a shot just to document the

behavior. I never thought it would make

a nickel when I clicked the shutter, but,

oddly, it has done pretty well.

Other personal favorites include

a fisheye close-up of an eagle ray

with the sky and clouds visible above

and the “starry shore” image of

bioluminescent plankton washing up

on a beach at night.

SF

// Unlike many shooters today

who have known only digital, you’ve

been doing marine-life photography

long enough to have made a

conscious decision about when to

transition from film to digital.

What motivated your migration?

dp

//

I transitioned in 2003 with a

Canon EOS D60 6-megapixel camera. I

live on Kona, Hawaii, and my neighbor

at that time was James Watt, one

of underwater photography’s most

prolific and talented shooters and

a digital pioneer. He started with a

Canon EOS D30, but I couldn’t get

enthused about the 3-megapixel

quality, so I waited for the next

generation. I’m not one to be right

on the leading edge of technology, for

there are too many failure points, but I

try to be not too far behind either.

Today I shoot a Nikon D4 and a

D800 topside and a D800 in a Nauticam

housing underwater. I use either Ikelite

DS161 or Inon Z-220 strobes . The Inon

strobes get the nod when I’m traveling

where weight is restricted, but when I’m

shooting in my home waters of Hawaii I

typically use the more powerful Ikelites.

I’m also using an Olympus OM-D

E-M5 now, primarily because of airline

restrictions. It’s a small mirrorless

camera that, coupled with a Panasonic

8mm fisheye lens and a Nauticam

housing, creates a small wide-angle rig I

can use with a polecam or to swim after

rapidly moving pelagic animals.

The digital revolution is exciting but

challenging. Clients can’t lose the original

film you had to send them like they did

with a few of my favorite slides. Instead

of FedEx and next-day deadlines it is FTP

service and same-day deadlines. With a

laptop and Internet access I can transmit

images to clients from anywhere. Plus

I can photograph things I could only

dream of before — like my shot of

bioluminescence on the beach. That was

a 30-second exposure at ISO 2500. I saw

it in my mind’s eye back in the days of

film, but only the digital technology of

my Nikon D700 could make it a reality.

It used to be that I opened the box

of slides, threw away the bad ones and

put the good ones into archival sleeves.

I was done until it was time to send

them to a client. Now I get home from

a trip with thousands of digital pictures,

and before I can get through those

I’m off on the next trip to accumulate

thousands more. Sometimes I feel like

Hercules having agreed to clean the

Augean Stables. Not that I want my

images compared to horse poop, but

you know what I mean.

AD

|

99