10

|

FALL 2013

FROM THE SAFETY STOP

//

P U B L I S H E R ’ S N O T E

I

find it hard to even write the

word “respect” without hearing

the Aretha Franklin tune in

my head (“sock it to me, sock

it to me”). As divers, one significant

association we should have with that

word is our relationship with the sea

and the coral reef.

This occurred to me recently

as I read a long and active thread

on an email list hosted by the

National Oceanic and Atmospheric

Administration (NOAA). Most people

who add their voices to the discussions

held there are extraordinarily

knowledgeable scientists speaking

about their particular marine biological

passions. I learn a lot just by lurking,

hoping that by osmosis I can become a

better-informed citizen of this blue planet.

The director of Alacranes Reef National Park in Yucatan,

Mexico, initiated this particular thread. The park administration

is writing a new management plan, and the director sought

comments on an idea to obligate divers to stay five feet away

from the coral reef to prevent damage.

As an underwater photographer, I find this recommendation

troubling. Besides the obvious consideration that quality

underwater photography can’t be done at a distance of five

feet away, and macro photography can’t be done at all, a larger

issue evolved in the ensuing conversations. Is the degradation

we see in our coral reefs brought about by scuba divers?

The following are a few of the scores of fascinating

insights proffered by those who are in a position to

speculate with authority:

“I regard the proposed ‘keep your distance’ rule as not only

misguided but counterproductive, sure to derail important

observations and documentation of reef life. In the 21st century,

divers who value ‘looking, not taking’ are among the ocean’s

best friends and most effective ambassadors. They are direct

witnesses to the swift changes that have taken place in recent

years and often document behavior and make observations

and discoveries of great scientific value. They also provide

knowledgeable, caring voices for corals, fish and other forms of

ocean life that cannot vote or speak for themselves. Damages

in the form of an occasional snapped branch or nudged sponge

are small compared with the impact of an improperly placed

anchor or the removal of fish, lobsters, conchs or other living

elements that make coral reefs prosper.” — Sylvia Earle, marine

conservationist and National Geographic Explorer in Residence

“In most parts of the world, especially the Caribbean,

diver damage is an undetectable signal compared with other

human-induced impacts or natural disturbances (storms,

bleaching, ocean acidification, overfishing and others). Yes,

it’s easy to point a finger at a diver touching the bottom or a

wayward gauge, but look at what happens in one winter blow

— not even a hurricane — or from turtles grazing on sponges

and you’ll see more damage than divers cause in a year. I’m

not saying we shouldn’t encourage good behavior, proper

buoyancy control and a better understanding of the marine

ecosystem, but realistically, putting significant time and effort

into diver regulation is not going to solve any problems.”

— Lad Akins, Director of Special Projects, Reef Environmental

Education Foundation

“Some divers and dive operators find reducing diver impact

appealing, because it is something they can do to help. I’m all

for that. The problem is that diver impact, while significant

for some small areas of reef, is one of the most minor impacts

on the world’s coral reefs. … If we want to save reefs, we

must stop global warming and acidification. We must also

reduce local impacts — primarily overfishing, nutrification,

chemical pollution, coral disease and introduced species such

as lionfish. … Climate change is the 800-pound gorilla in

the room. If we don’t do anything about that, we could stop

R-E-S-P-E-C-T

b y S t e p h e n F r i n k

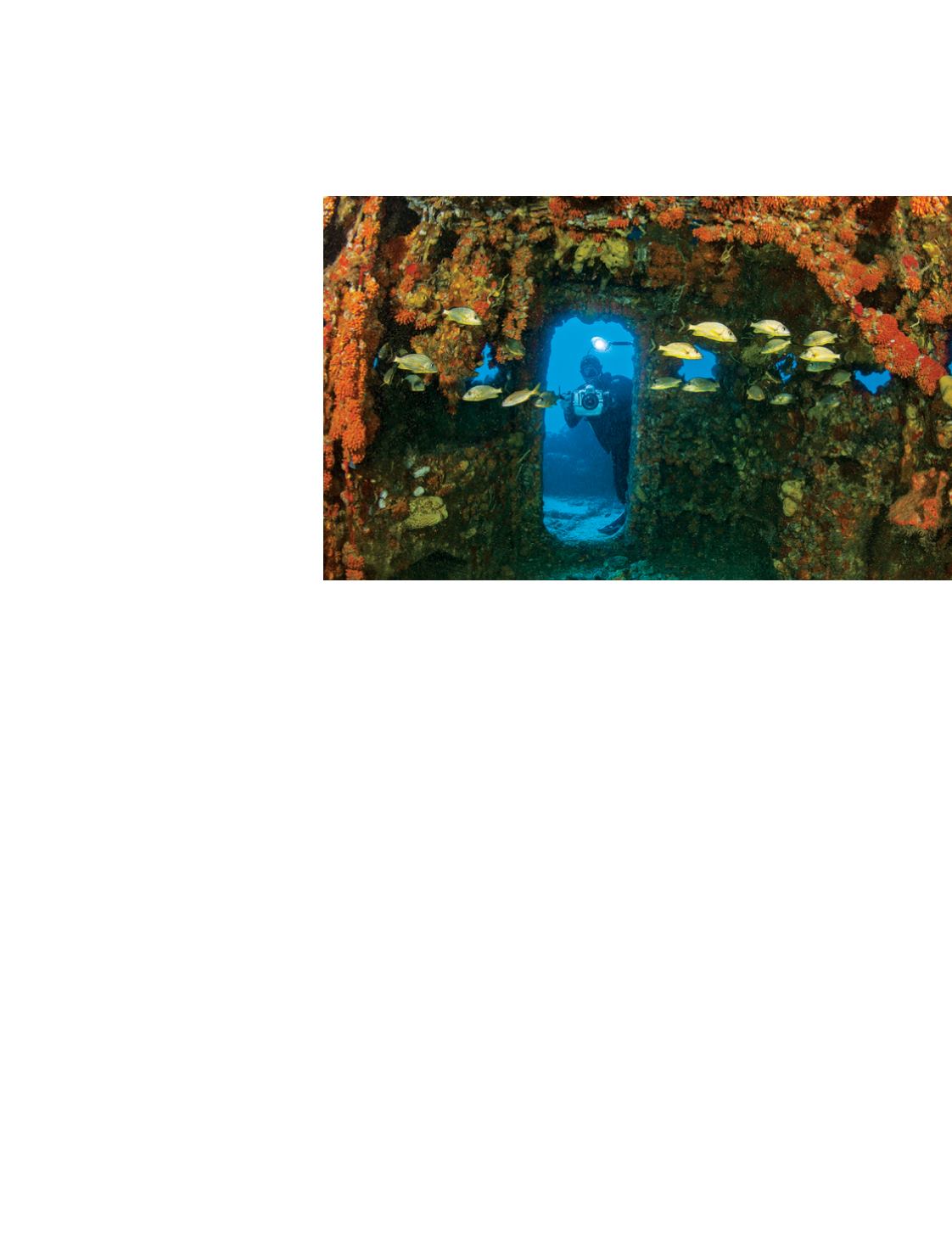

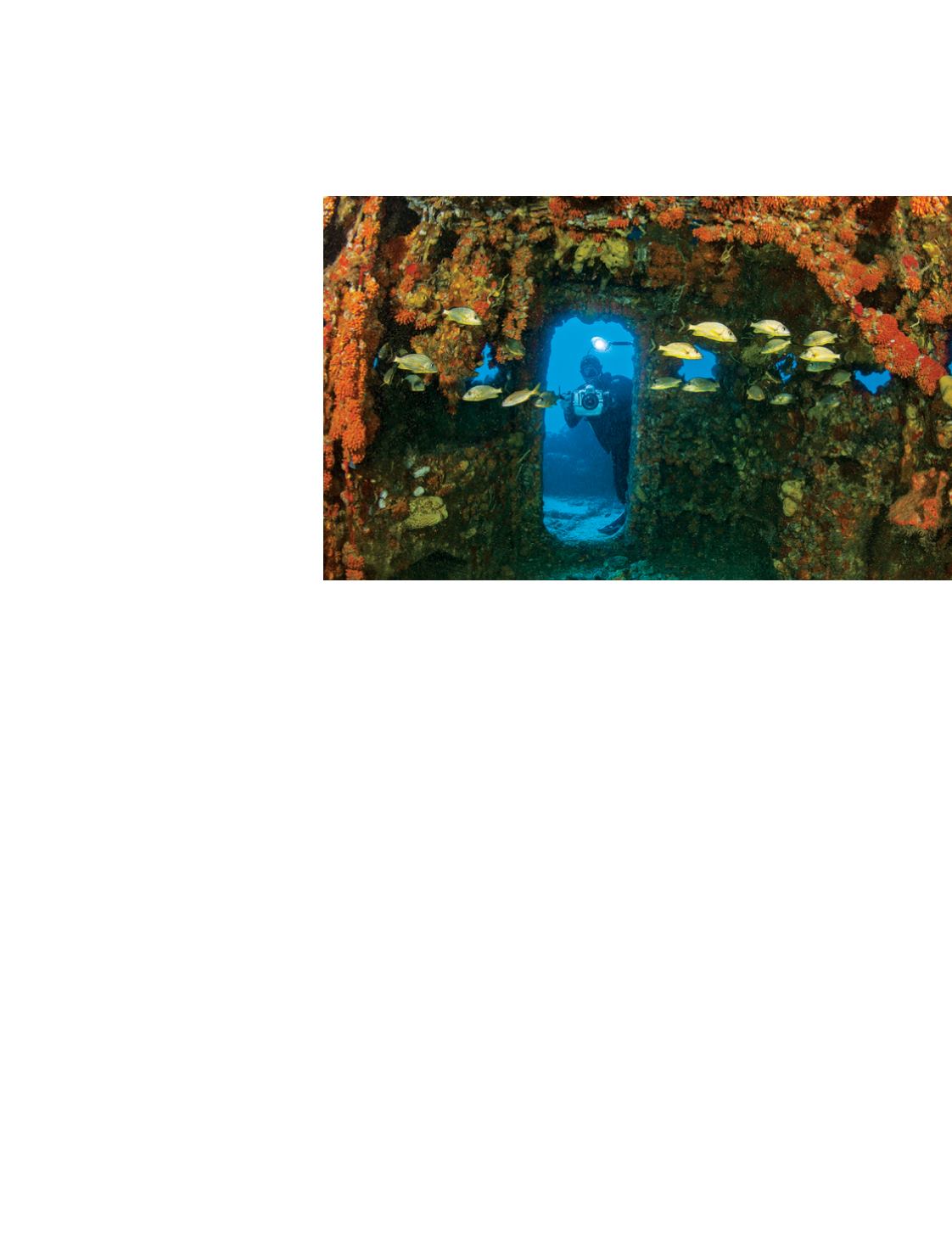

TYRA ADAMSON