a fixture 20 years later, forever

vilifying the worm.

Although they’re known

worldwide, much about these

secretive worms remains a

mystery. For starters, even

though more than 350 species

have been scientifically described

in the genus Eunice, a great

deal of the early work needs

revision. Even for the few Eunice

experts around, it is virtually

impossible to identify one from

a photograph, and it can even be

challenging with the specimen in

hand. Genus members, all armed

with their notorious mouthparts,

range from small animals only

inches long to titans such as the

one we saw in Lembeh. A few

collected specimens measure

10 feet in length, and one

Australian colossus is reputed

to have reached 20 feet. Perhaps

unsurprisingly, the worms’ natural

history also remains a mystery.

After the other divers lose

interest and wander away, I

remain kneeling beside the

beast, transfixed. I’m particularly

intrigued by how the jaws collapse

back onto themselves to disappear

inside the worm’s fleshy head.

No less bewitching is the sheen

of rainbow iridescence rippling

along its back. In the midst of my

reverie, the worm offers a rare

gift — a reward for my chronic

curiosity — releasing a stream of

smoky spawn into the night.

I have an even more memorable

Bobbit worm encounter on a

subsequent trip to Dominica,

a lush volcanic island in the

eastern Caribbean. During a

safety stop at the top of an

offshore pinnacle, my dive guide,

Imran, points toward a hole in

the reef. Glancing down I see the

unmistakable form of a large reef-

dwelling Bobbit crawling through

the shadows.

In one of those “What was I

thinking?” moments, I slip my

steel wand beneath its body and

lift. The worm comes out without

the least bit of resistance. Imran

retreats, his eyes bulging. Amazed,

I keep lifting until the creature

dangles in a great U from my

stick. Astonishingly, the famous

jaws remain retracted. I slip my

upturned hands beneath the

belly and watch as it crawls over

my palms like a pet corn snake.

Measured against my height, the

body appears to be at least 6 feet

long. I drape the worm across the

bottom and snap a portrait before

inserting the head inside the hole,

where it calmly disappears.

Back aboard the boat, Imran is

dancing in disbelief: “That’s crazy,

man. You’re lucky to have a face.”

“Yeah,” I answer, still attempting

to sort through what just happened

myself. “I guess I am lucky.”

Word travels fast on Dominica,

and the next morning at least a

half dozen disbelievers meet me at

the dock. Although few locals on

the island dive, everyone has been

raised with horror stories about

the monster worms inhabiting

their waters. In a weird sort of

way, you could think of the Eunice

worms as island mascots. After

retelling my tale for a third time,

I retrieve my computer from my

room and display the portrait.

“No, mon. Look at dat. It’s

obvious de worm is some kind

of sick,” one skeptic claims. The

others gathered around the screen

nod in agreement.

“What else can I say?” I reply.

“You can believe it or not.”

AD

|

31

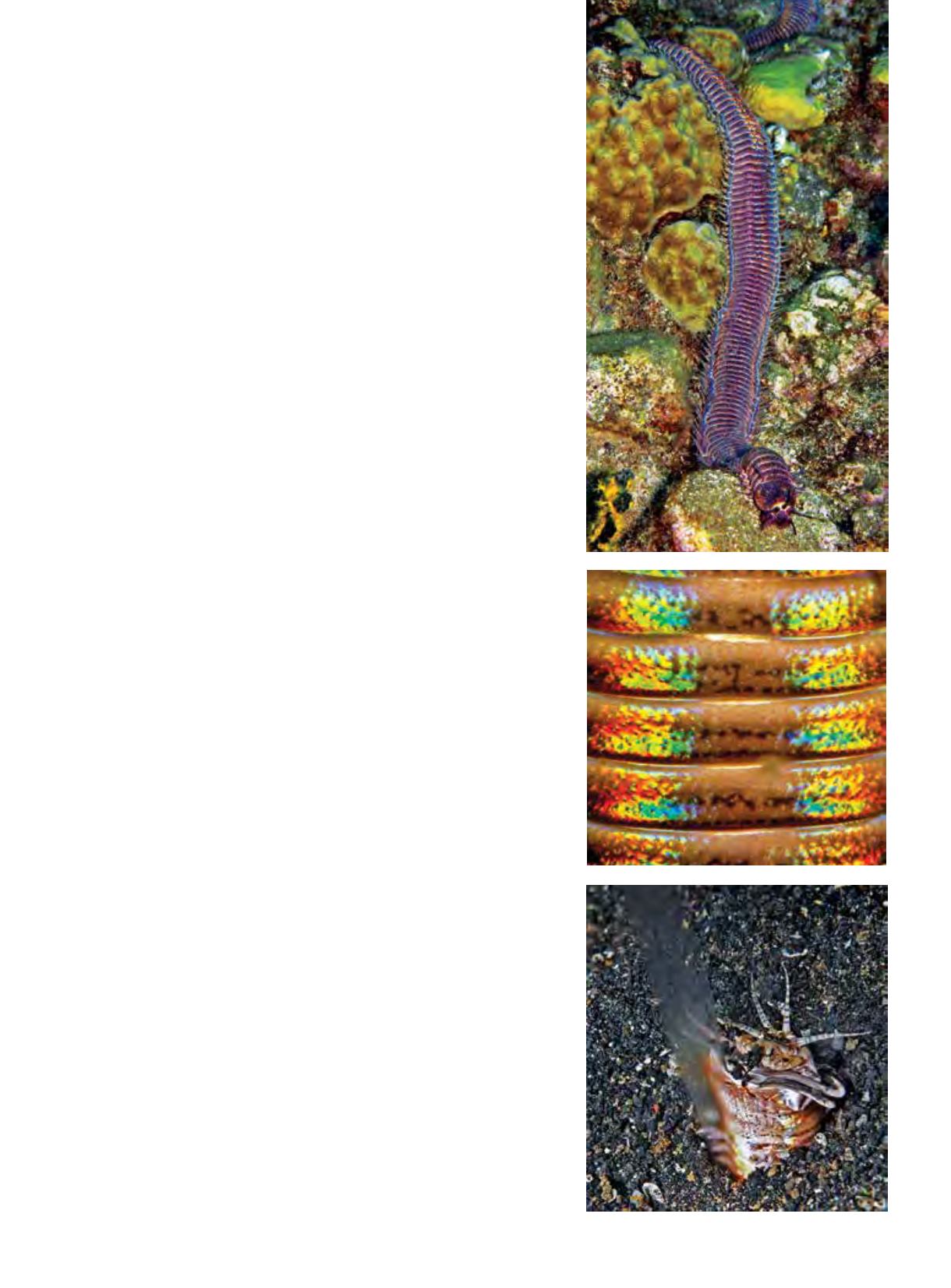

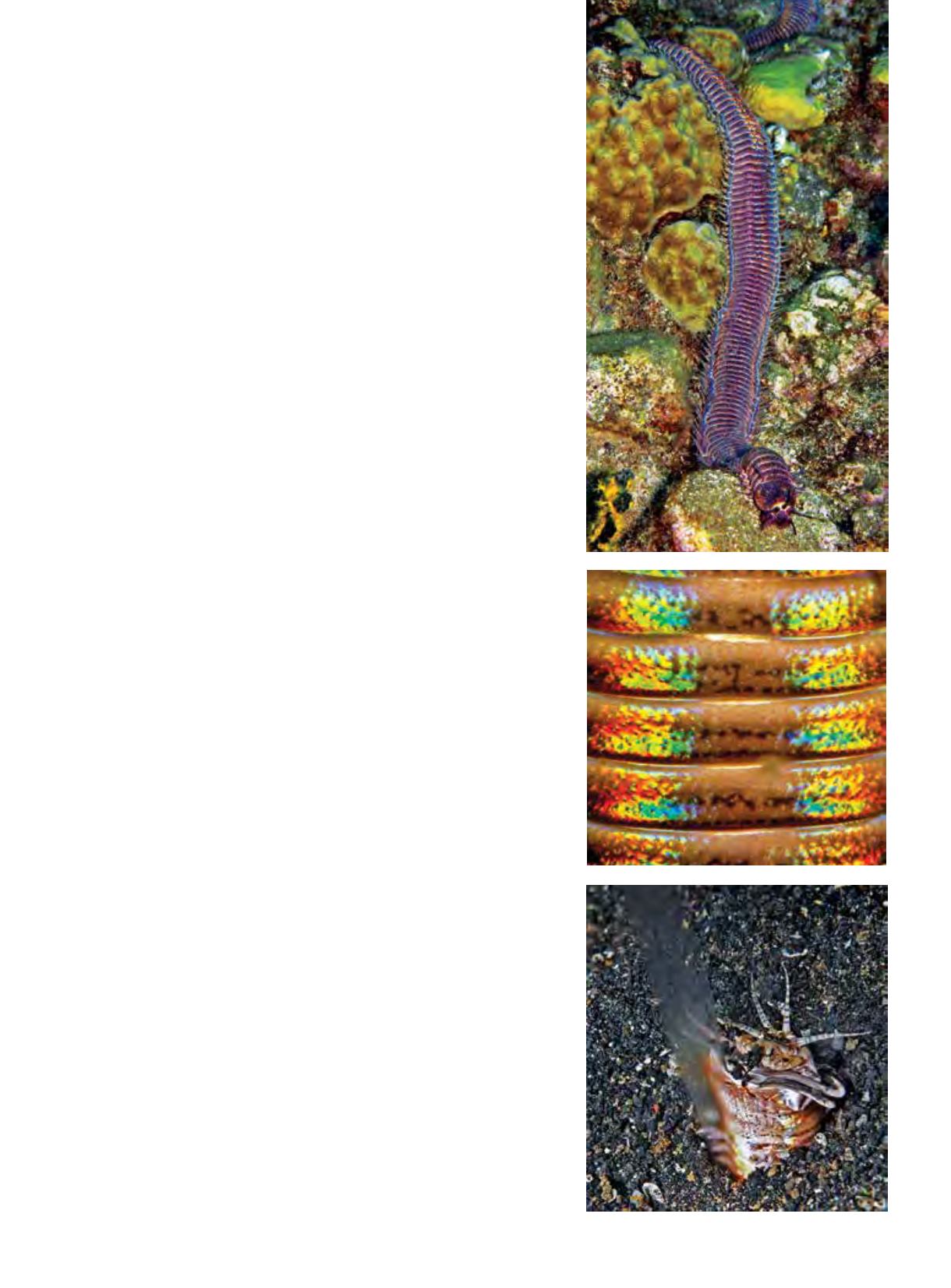

From top: This Bobbit worm in

Dominica spreads across the sea

floor for a portrait; the iridescent

skin of a Bobbit worm; a Bobbit

worm spawning.

Opposite: A Bobbit worm springs

from the sand in Lembeh.