LIFE AQUATIC

//

40

|

FALL 2014

and waiting, might be momentarily confused with

so many identical fish packed into a living, moving

wall. Late in the afternoon the predators become

more active, and their anxious prey pack even closer

together. In contrast to the quickly moving prey fish,

motionless adolescent longfin spadefish frequently

hover above the wide-eyed scad, watching the parade

and perhaps wondering what all the hurry is about.

Each locale offers slightly different environmental

factors — varying depths, light intensities, currents,

plankton availability, nutrient levels, water chemistry,

etc. — that affect which marine life colonizes a

structure. When new pilings are put in place, they

act as open territory, fit for colonization by hundreds

of sessile organisms. In a matter of days, marine life

begins to claim territory upon the thick wood or metal

supports. Barnacles, hydroids, bryozoans, crinoids,

mussels and innumerable barely visible creatures settle

onto the pilings, where certain cues signal for them to

metamorphose into thriving, mature communities. The

quick succession of life shows how prolific larvae are in

the overall tropical marine environment. Evolutionarily,

it pays obvious dividends for a species’ planktonic larvae

to be able to settle and metamorphose immediately

upon sensing the right environmental factors.

In some areas where coral reefs are not profuse,

docks and piers can potentially increase fishery

resources, either by drawing in dispersed populations

of fish or by creating a more suitable habitat for the

escalation of fish populations. Many organisms that

typically live in cavern environments are also found in

the dark cavities of piers and docks.

Considerable variation may be expected in different

portions of one set of docking facilities and certainly

between docks placed in ecologically different situations.

No two docks are ever alike in terms of their aggregated

marine life. Most illuminated spaces will tend to be

monopolized by photosynthetic organisms, and partly

or completely shaded areas are apt to have assemblages

of more unusual animals. Many of the organisms living

under floats or on pilings are those normally found at

deeper parts of the intertidal or subtidal zones. On a

pier or dock, they can live close to the surface without

danger of exposure to intense sunlight.

Just about any structure under which divers (and their

gear) can slither will present strange, bottom-dwelling

critters and unique environmental scenery vastly different

from that of coral reefs. While the Pacific offers any

number of exhilarating dives over bottomless drop-offs,

along deep pinnacles and through swift channels where

large fishes roam, piers and docks are consistently rich in

bizarre, photogenic inhabitants. For photographers these

man-made marine habitats are almost always productive

for both macro and wide-angle photography. Pier pilings,

dock moorings and surrounding habitats are loaded

with the odd creatures for which divers have a special

affinity — from tiny harlequin shrimp to lumpy frogfish

to leaflike waspfish. While many divers focus on a pier’s

smaller critters, larger predators such as resident giant

moray eels or tassled wobbegongs, who appreciate the

culinary abundance at these locations, will also frequently

patrol the waters around these man-made structures.

Each marine ecosystem, each underwater habitat,

each niche with its associated wealth of generalist or

specialist inhabitants is part of the all-encompassing

biosphere. No trophic level or species exists in

isolation. Even piers and docks, which bear various

collections of odd and intriguing creatures and their

own distinctive food webs, are intricately tied to the

open ocean. These structures of wood, concrete, nails,

ropes and tires are merely part of a dynamic puzzle

whose pieces extend from DNA molecules to entire

ecosystems and whose effects radiate through the

world’s oceans.

AD

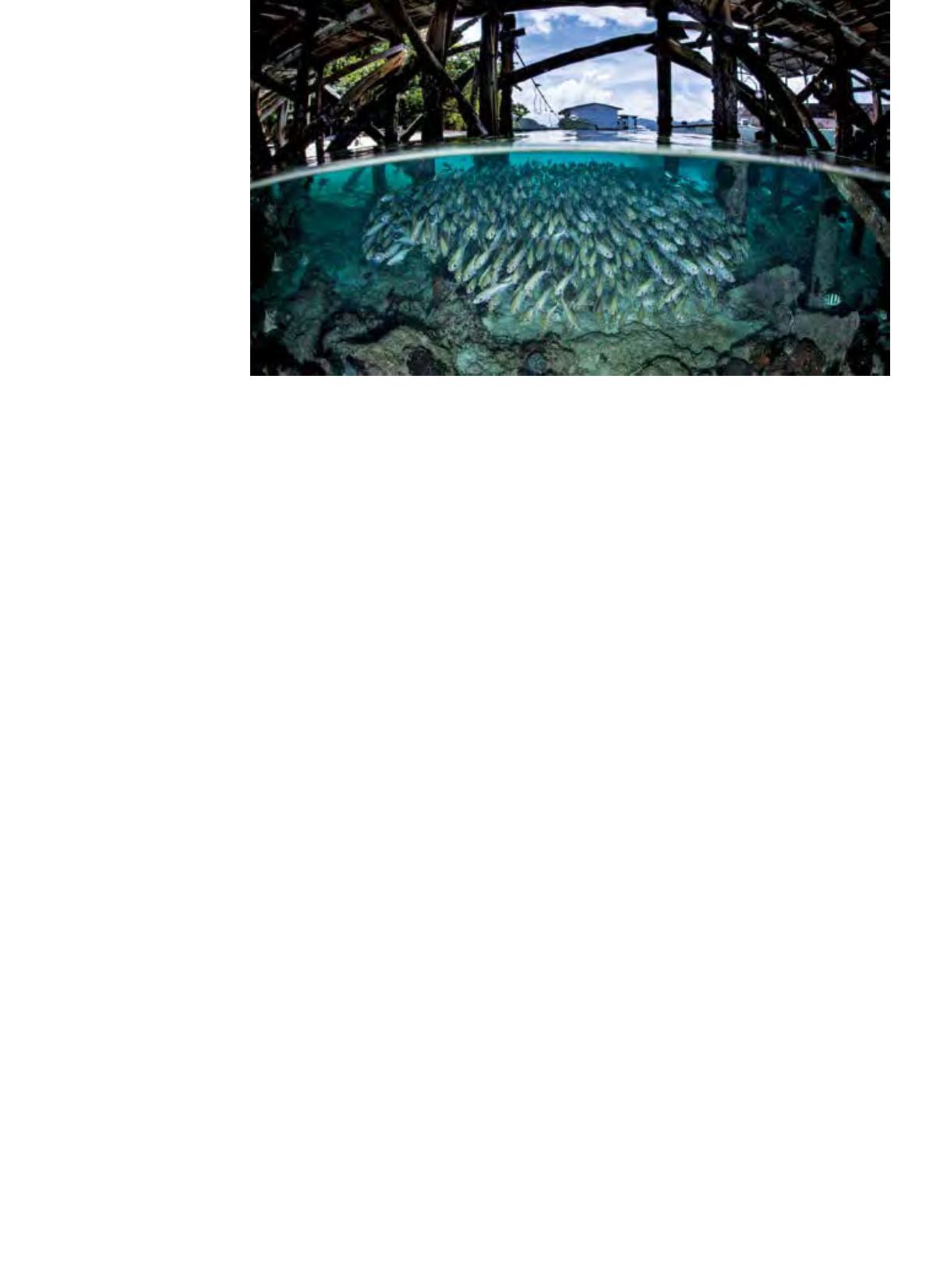

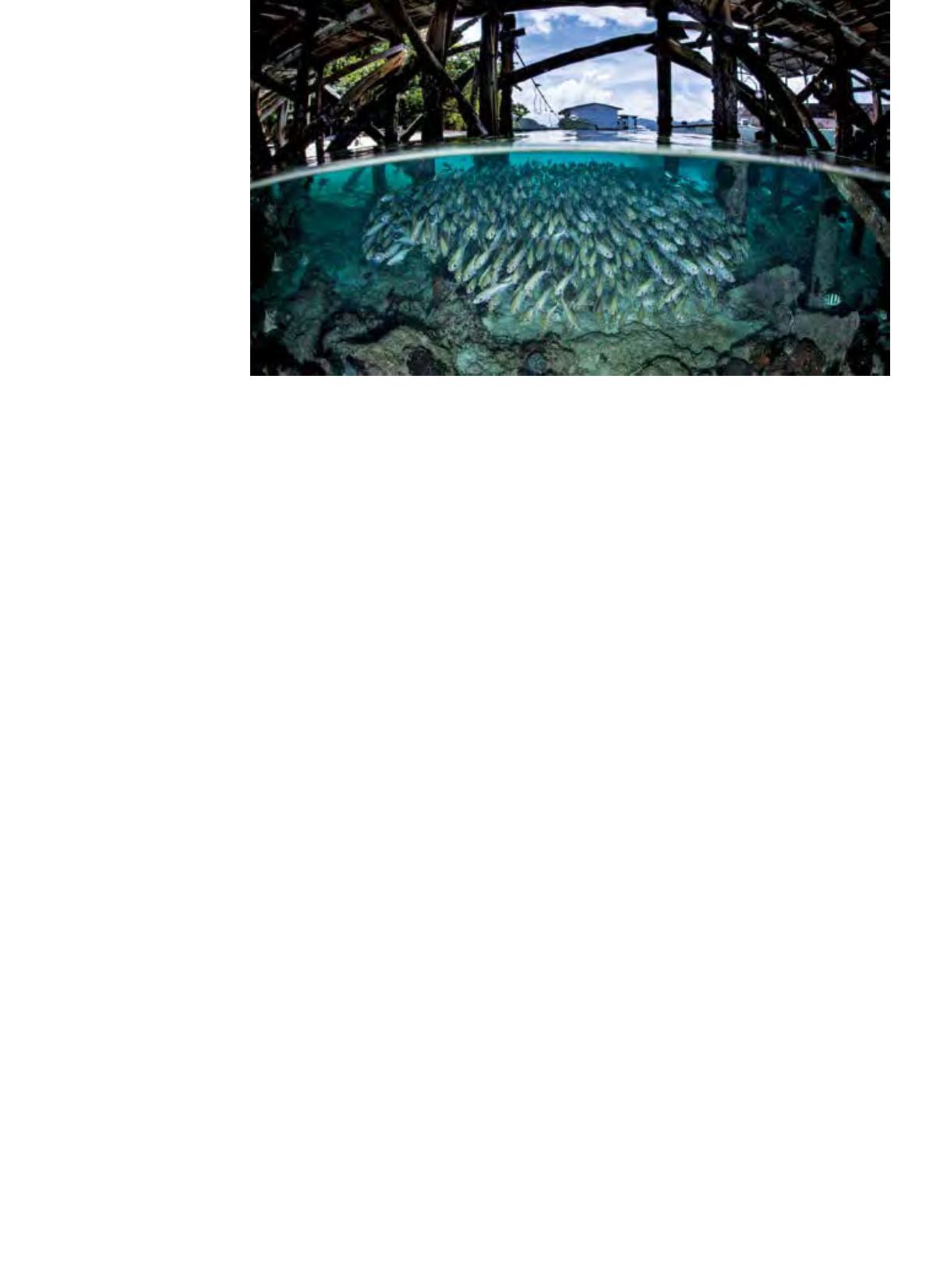

Caught in the open, schooling

scad are easy targets for

marauding trevally and small

sharks. These silvery prey-fish

often seek refuge under

docks or piers, which attracts

larger predators.