The wavelength of light used in most fluo torches

is a narrow band of blue, somewhere between 440-

480 nanometers (depending on the manufacturer).

Fluo diving differs from ultraviolet (black-light) diving

because UV light is in the sub-400nm range. Some

companies produce UV torches for underwater use

because invisible UV excitation light has the advantage

of requiring no additional filters, but researchers have

also discovered that blue light is more efficient in

stimulating green fluorescent protein (GFP) and its

mutations, which emit colors other than green.

Blue light is so effective because (as we all know from

our beginner open-water course) it is the only light

available at depths beyond about 30 feet, which means

that this is the light in which organisms such as coral

have evolved over the eons. Most UV light from the sun

bounces off the surface of the water, and the light that

penetrates makes it only a few inches, rendering UV

light an inefficient light source for fluo diving.

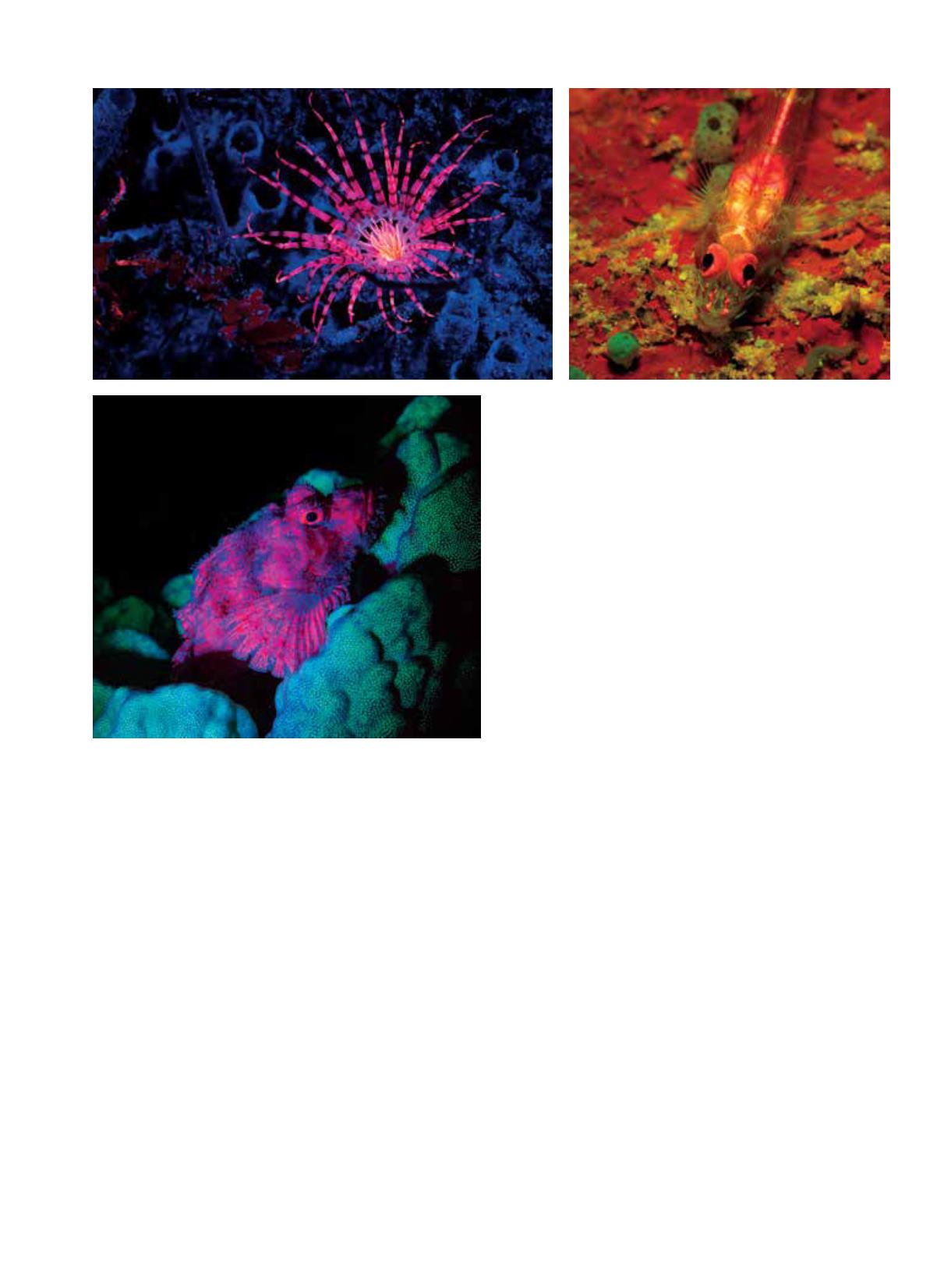

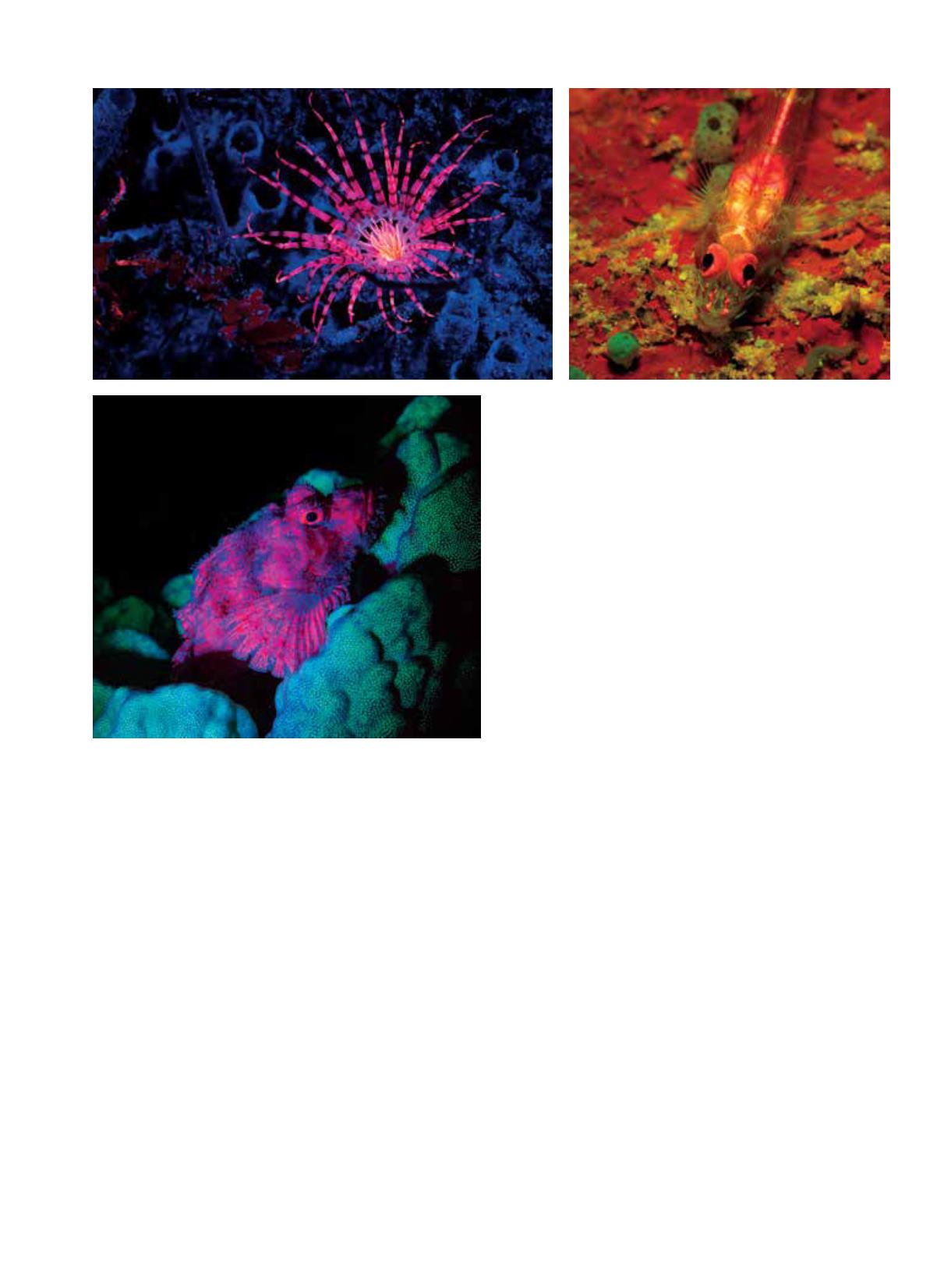

Not all marine organisms exhibit the fluo effect,

but for those that do the visual demonstration can

be dramatic. Some examples of fluorescing species

include anemones, a variety of shelled animals, some

types of fish, coral polyps and both soft and hard coral

structures. The terms “hard” and “soft” coral can be

a bit misleading. For example, brain coral is often

mistaken as hard coral, but it is considered to be in

the long polyp stony (LPS) family of soft coral. The

small polyp stony (SPS) family of coral is similarly

misrecognized as hard coral even though it is actually

soft. These misidentifications are due to the fact that,

in both cases, the living coral is made up of tiny soft

creatures that live and die building up large stony

structures over the course of decades. Interestingly,

these two species are the coral subjects that emit the

most fluo effects. Examples of soft coral that rarely

fluoresce are generally in the Alcyonacea order; it is

important to note, however, that in all groups there are

exceptions to the rule — just like with people.

The basic point is that there is great variance in

the types of coral that fluoresce, and we have not yet

determined all of the rules of this phenomenon. This

is one of the allures of fluo diving: You can make your

own discoveries as a citizen scientist.

Many people think that fluo diving is done only for

views of the spectacular colors or for the purposes

of underwater photography. It certainly meets those

expectations and can indeed be a life-changing

experience, but it is also much more than that. Fluo

diving has become an indispensable tool for coral-health

research efforts and coral-propagation census analysis.

If you come upon a polyp or drifting coral larvae with

white light, you will see little or nothing; with the

|

45

Clockwise from upper left: An anemone emits fluorescent light,

unlike the surrounding sponges and corals. Without fluo dive gear

it would be impossible to observe the colors of this blenny. It is

not well understood why scorpionfish and others have evolved

to fluoresce. To learn more or to purchase fluo dive gear, visit

FireDiveGear.com.

BRIAN MCHUGH

STEVE LOCK

LYNN MINER