I

was recently in Cuba (see “Jardines de la

Reina: Cuba’s pristine paradise” on Page 68)

leading a photo tour on a liveaboard. Since it

was summer and school was not in session,

my daughter, Alexa, was able to join me. It

was a great opportunity for us to spend some

quality time together doing what we love: scuba diving

and being around interesting marine animals.

One of the things I looked forward to was an

encounter with crocodiles in the mangroves that I’d

seen photographed by others. Dive operators have

been conducting such encounters for two decades, and

they have learned that divers can interact safely and

reliably with some of the subadult American crocodiles

(

Crocodylus acutus

).

The whole process was pretty interesting. We would

travel to a spot commonly visited by crocs, and the

guide would call out, “Niño, Niño!” The crocodile he

had in mind was obviously habituated to encounters

with snorkelers and rewarded with raw chicken for

good behavior. This is not to say the interaction is

guaranteed though — one day we got skunked. But

the second morning was quite productive. Niño came

swimming out to us, and we got in the water with

snorkels. I had a large housed camera and strobe that I

could put between the croc and me. My daughter had

her GoPro on a selfie stick that she could use to fend

off any approaches that were too close for comfort.

Throughout the 40-minute encounter we were

never alarmed; in fact, we were excited about our

good fortune to have been there at high tide (for

optimal water clarity) and about the crocodile’s

willingness to get close. The fact that this all

happened in a gorgeous mangrove and seagrass

environment made it all the more special — such

places are typically far more turbid. No one should

extrapolate from our good luck with this particular

crocodile that the more aggressive species in Australia

or Africa are approachable. While this particular

encounter was mellow and benign, snorkelers in Raja

Ampat, for instance, have been killed by crocodiles

inhabiting the blue water mangroves.

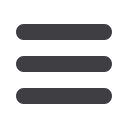

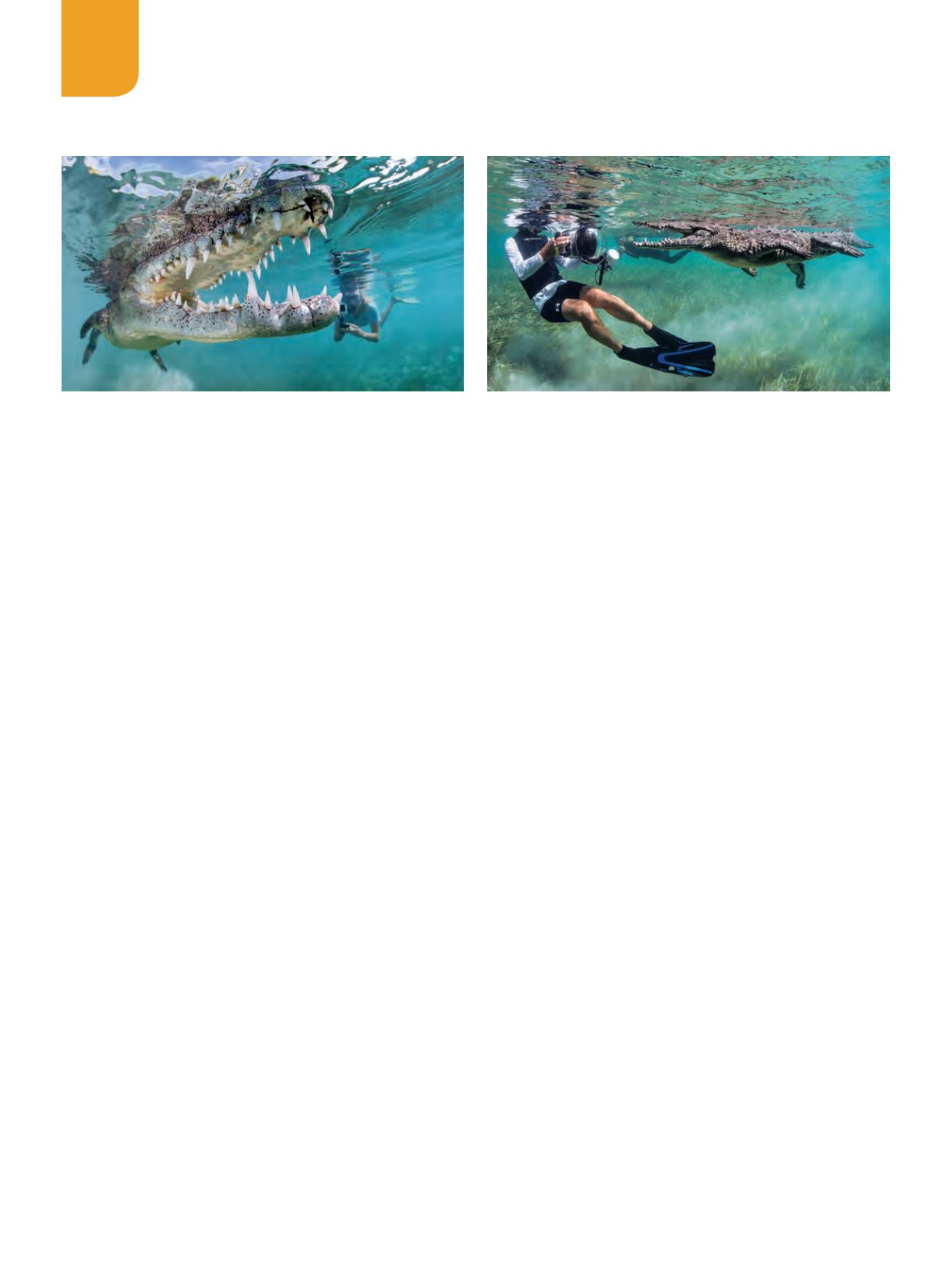

Photographer Dena Mintz captured the photo above

of me at work with my camera; because both the croc

and I were on roughly the same plane, the size reference

is pretty authentic. But as I maneuvered around the

front of the croc and got closer to its open mouth with

my extreme wide-angle lens, an optical phenomenon

called “perspective distortion” occurred. The object

in the foreground (the open mouth of the crocodile)

appeared unnaturally massive and intimidating relative

to Alexa swimming in the background. Shooters with

experience in wide-angle photography know about this

and can recognize it in photos, but the image provoked

strong reactions from some members of the public.

I distribute my images through a variety of stock

photography agents, and one works with mass media

in the UK and Australia. The crocodile shots went

viral. I’d like to think it’s because they turned out so

well, but in reading the comments I could see it was

mostly because so many people thought it was very

irresponsible for a father to expose his daughter to

such danger. Here are some examples

of the comments (from

grindtv.com/wildlife/daughter-swims-dangerously-close-crocodile-father-

takes-photos-video

):

14

|

FALL 2016

FROM THE SAFETY STOP

PUBLISHER’S NOTE

PERSPECTIVE DISTORTION

By Stephen Frink

These two photos were taken nearly simultaneously, both with full-frame

fisheye lenses. For the photo on the left, the camera’s dome port was within

4 inches of the crocodile’s teeth. For the photo on the right, the shooter was

4 feet away from the action, which significantly altered the perspective.

FEAR AND LOATHING IN SOCIAL MEDIA

DENA MINTZ

STEPHEN FRINK