36

|

SPRING 2016

LOCAL DIVING

WASHINGTON

Lingcod are everywhere. Some valiantly guard clutches of eggs that

look like balls of Styrofoam. At 40 feet deep, I see nestled in a forest of

ghostly white plumose anemones a 4-foot-long monster big enough

to make one’s blood run cold. Rare on many Northwest reefs thanks

to overfishing, lingcod numbers (and epic sizes) here are proof that

protection works. All marine life in this underwater park is protected, so

the rockfish, starfish and cabezon — along with the big brutish lingcod

with his bullying stare — should be here in the future, fat and happy.

With fingers intact we continue deeper, acting on a friend’s tip that

a wolf-eel was recently seen hanging out at 55 feet. I’ve seen both

juveniles and adults at Keystone and never tire of their Muppet faces.

But a pile of crab carapaces and scallop shells catches my eye, and I

forget all about

Anarrhichthys ocellatus

. The messy midden of a well-fed

giant Pacific octopus (GPO in local diver-speak) is a lure I cannot resist.

Flattening myself on the sand like a halibut, I shine my light into the

shadow under the large rock beside the garbage heap. Sure enough, I spy

a tangle of tentacles with suckers the size of silver dollars. It appears to

be a good-sized specimen at 7 or 8 feet across, perhaps.

For the next 10 minutes we wait, wiggle our fingers, mutter curses

and say prayers; we even offer up tasty-looking bits of already devoured

shellfish, all in hopes of coaxing the wily devilfish from its den. But

there’s no luck today. This octo is more patient than we are, and

probably smarter, too. The current, barely noticeable for the first half of

our dive, is now steadily building, bending the plumose anemones and

trying to tug us toward the jetty end and out into Admiralty Inlet. It’s

time to go. We retrace our fin kicks and return to shore.

Current is the lifeblood of the Pacific Northwest marine ecosystem,

critical for moving the nutrient-rich waters that nourish life large

and small. And things can really get moving at the deeper end of the

breakwater during large tidal exchanges. To safely and enjoyably dive

Keystone, schedule your dives for slack water, the period of minimal

water movement that occurs between changes in current direction. On

days with small exchanges, slack may last 90 minutes or more. On days

with large exchanges, you may have only a few minutes of true slack, but

there is usually enough time for a dive.

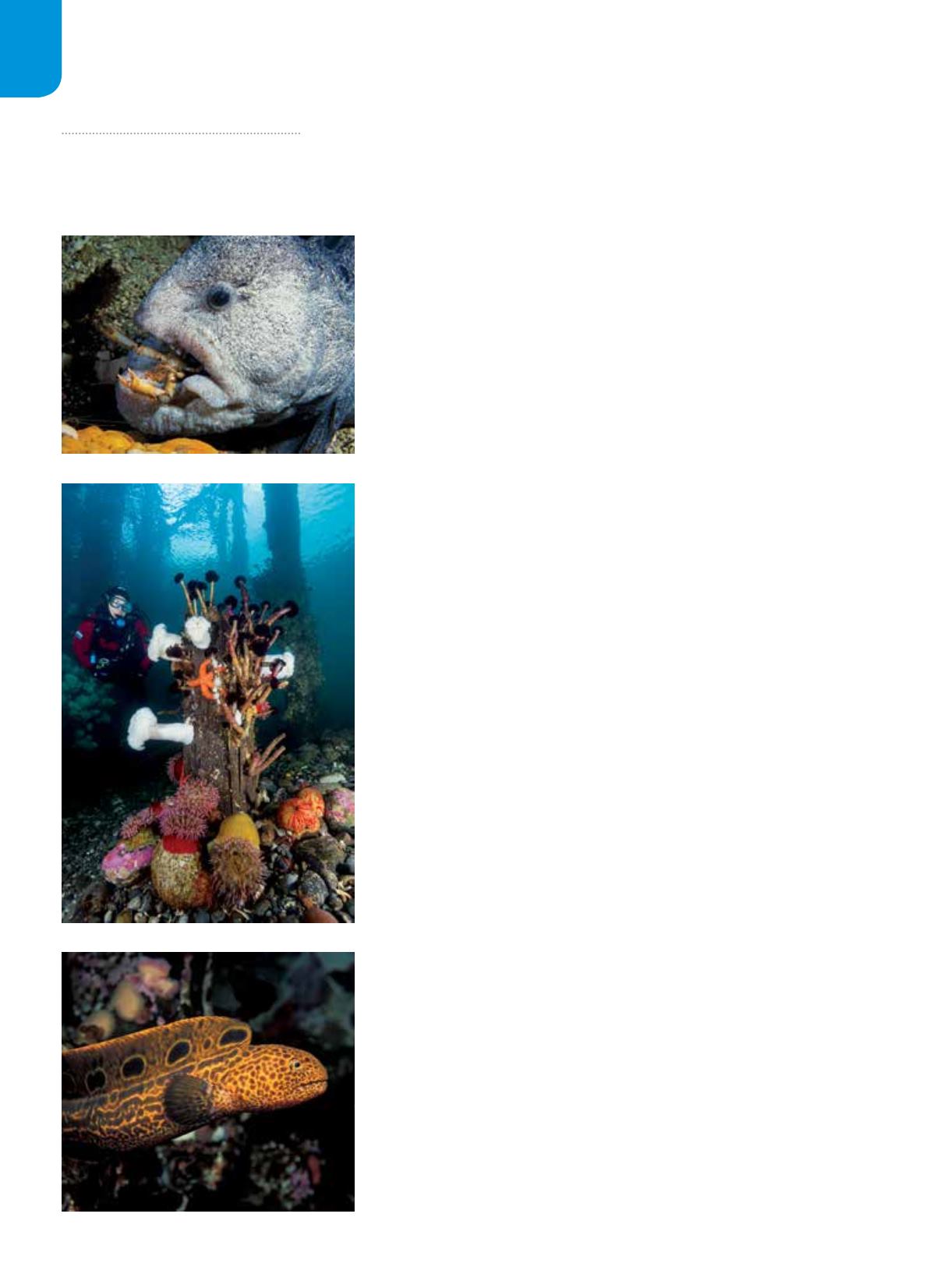

Keystone’s second dive site should also be timed for slack tide. The

subsea scenery here provides a nice contrast to the jetty’s jumbled

rocks. While weaving between the wharf ’s wooden pilings between

10 and 35 feet, we move slowly to allow close examination of the

encrusting invertebrates. Bouquets of giant feather-duster worms

extend deep purple feeding plumes into the water to snag passing

plankton. Brightly striped painted anemones bloom in green, red,

yellow and mauve — it’s easy to see why they’re nicknamed dahlia

anemones. Sponges and the ubiquitous

Metridium

anemones carpet

the vertical supports, while leather stars and blood stars use tube feet

to march across the cobbled bottom.

Up pilings, around, down and back up again, we search the matrix

with masks pressed close to the many layers of life. A male buffalo

sculpin is parked on lime-green eggs, while jellyfish drift by. Snails lay

whirls of eggs as the usual crustacean contingent of shrimps and crabs

go about their scuttling business. These pilings are high-rise condos

forming a city in the sea.

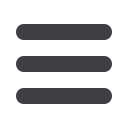

From top:

An old male wolf-eel chomps

a crab; a drysuited diver explores the

maze of pilings underneath the wharf; an

18-inch-long juvenile wolf-eel sports much

brighter colors than its parents.