T

he day started like any other June day. It

was warm, a little windy and perfect for

diving one of our favorite training sites:

Lake Mohave, Ariz. Our instructor

team was teaching three classes that

morning — Open Water Diver, Peak

Performance Buoyancy and Underwater Navigator —

and we had a productive morning of dive training. After

successfully completing the certification dives, a group

of nine of us decided to delay packing up our gear and

instead celebrate with a dive for fun. We headed to the

site of a sunken cabin cruiser two coves over.

After a short hike in full gear over a couple of small

rises in the desert, we arrived at the entry point. As soon

as we got there we heard yelling — a woman floating

in an inner tube a short distance offshore was clearly in

some kind of distress. A member of our group swam

over to assess the situation and learned that someone

had gone underwater and had not come back up.

Our training kicked in. One member of our group

returned to our base camp to phone for emergency

assistance, two swam to assist the woman and get

a better understanding of what had happened, and

the rest descended to conduct a search pattern. Five

minutes into our search I discovered an unresponsive

man on the bottom in approximately 40 feet of water.

As I approached him I formulated what I would do

when I surfaced with him, mentally running through

the countless scenarios that have unfolded in the

Rescue Diver courses I’ve taught.

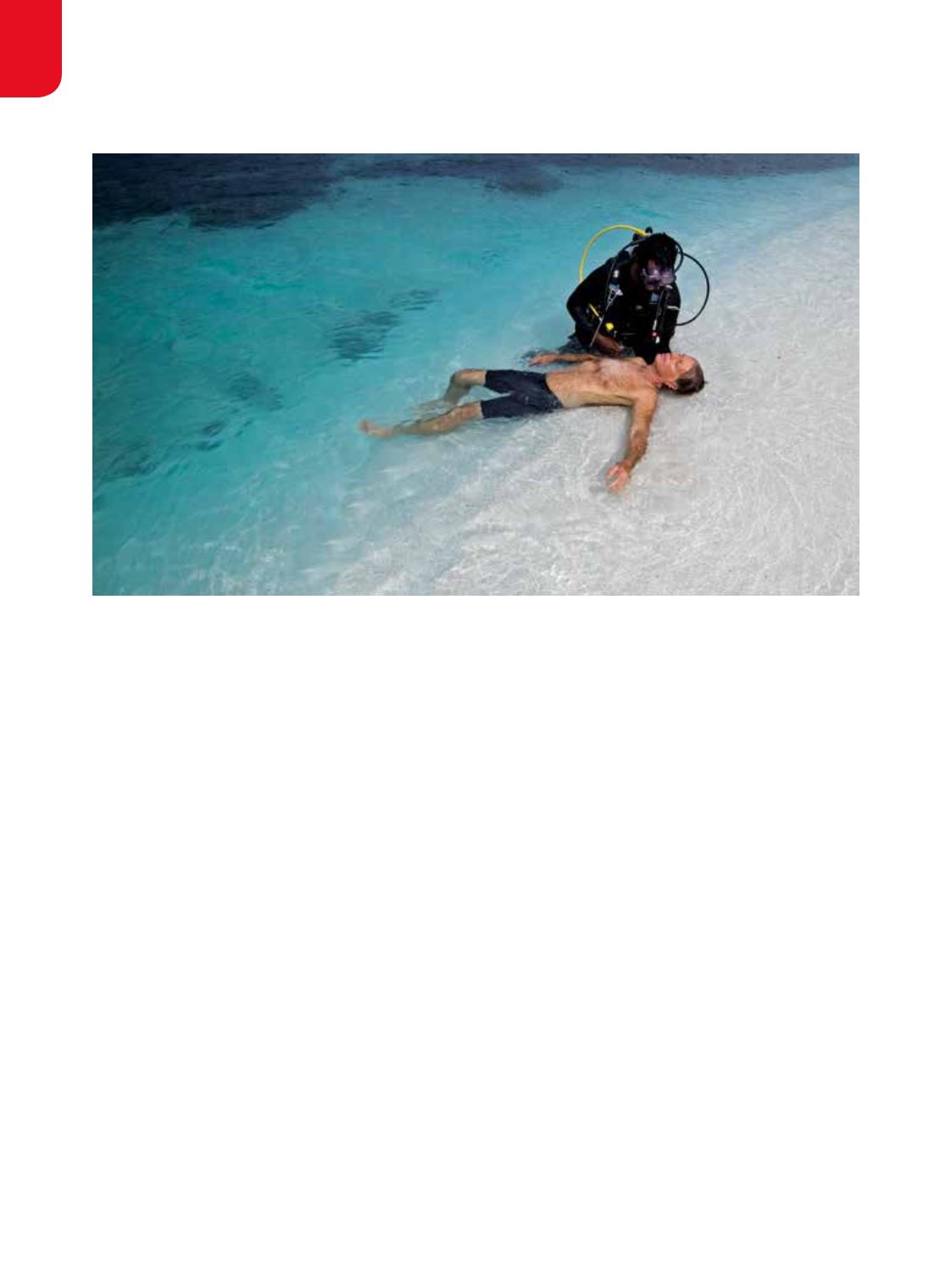

When I reached the man I grasped him, brought

him to the surface, held his head in a way that would

ensure his airway was open and began to administer

rescue breaths as I swam with him to the closest point

on shore. The rest of the team helped move him onto a

flat part of the rocky ground. One instructor deployed

a pocket mask that he always carries in his BCD, and

we immediately began CPR. Every couple of cycles we

shifted responsibility for compressions and ventilations

among the rescuers — it’s exhausting to keep up

effective CPR as the adrenaline begins to run low. We

continued performing CPR for 20 minutes while we

waited for the arrival of emergency medical services.

The National Park Service had dispatched a couple of

boats, and we placed the patient aboard one of them so

he could be moved back across the cove to where the fire

department paramedics could take over care. They placed

him into a helicopter for transport to the hospital.

By the time the ordeal was mostly over, one of our

divers started having some breathing issues due to

By Curtis Snaper

RESEARCH, EDUCATION & MEDICINE

SKILLS IN ACTION

Teamwork and Training

58

|

SPRING 2016

DENNIS LIBERSON