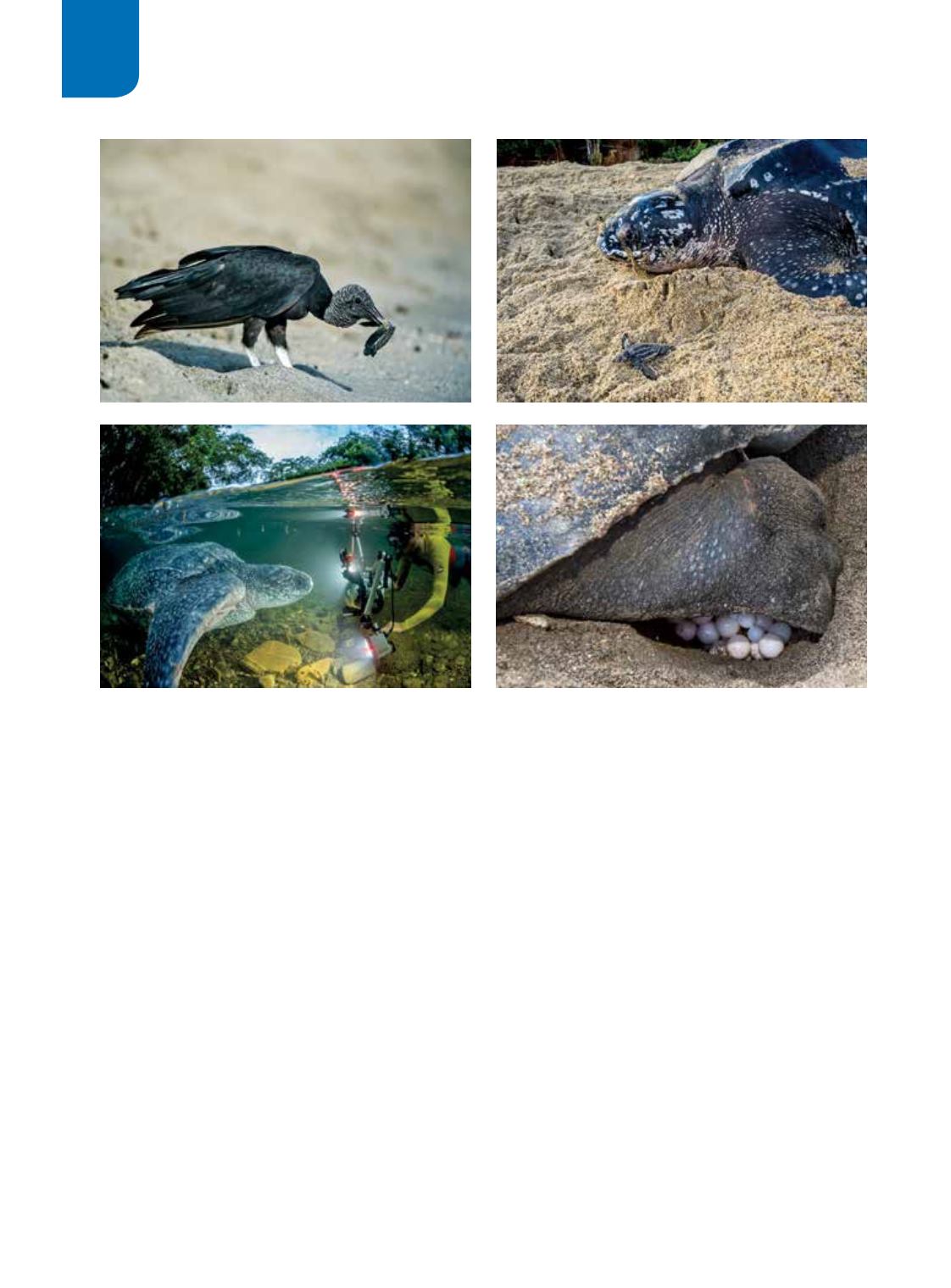

A 100-million-year-old species, the leatherback is not

your ordinary sea turtle — it’s almost an insult to call

it one. In a class entirely its own, it is one of the largest

reptiles, capable of reaching 7 feet and 1,500 pounds

or more. Shaped like a giant, hydrodynamic teardrop,

leatherbacks can dive to more than 3,000 feet — deeper

than most whales — to eat jellyfish, their main food

source. When feasting on these gelatinous invertebrates

in the subarctic, leatherbacks keep their bodies warmer

than the surrounding water, thanks to their huge body

mass and a sophisticated circulatory system. This

special adaptation, called gigantothermy, allows these

creatures to go where other reptiles would freeze and

extends the range of the species to the point that it’s

one of the widest-ranging animals. They are citizens of

the world: Indonesian leatherbacks travel to Monterey

Bay, Calif., to forage, while Trinidad’s leatherbacks visit

eastern Canadian waters in the summer. One tagged on

Panama’s Caribbean coast was later found alive in a net

in Italy and successfully released.

Our adventure with that lost leatherback on our first

morning in Trinidad capped off what would be the first

of several grueling all-nighters on our trip. While I have

photographed them underwater where I live in Florida,

I didn’t have any photos of nesting leatherbacks. When

one of my buddies with local connections in Trinidad

suggested we head down there, I agreed immediately.

During peak nesting season in May and June, some

of the busiest beaches in Trinidad receive nearly 400

nesting turtles every night.

For the next week we settled into a demanding

routine: After dinner we and our guides would head out

in pairs to local beaches to work. The red glow of our

headlamps revealed clusters of leatherbacks — completely

oblivious to our presence — entering and leaving the

pounding surf and sometimes even crawling over each

other and accidentally destroying nests. These excursions

were arduous. The uneven terrain, heat, sand, darkness,

smell (from broken eggs and dead embryos), rain and

biting insects made it extremely tough to remain focused.

We would return to our simple accommodations

in the morning for breakfast, showers and sleep.

Random turtles nesting under the blazing tropical

sun or unlucky hatchlings being devoured by vultures

and frigatebirds broke the midday quiet and made us

scramble for our cameras. In the late afternoons we

explored the coastline by boat with fishermen, who

took us to a staging area offshore where leatherbacks

24

|

WINTER 2016

DIVE SLATE

LEATHERBACKS