ALERTDIVER.COM

ALERTDIVER.COM

|

91

most significant evolution in decompression safety

for recreational diving in the past 30 years. The three-

minute stop is good, but it is even better if it follows

a progressive multilevel profile and is extended as gas

supply and conditions allow.

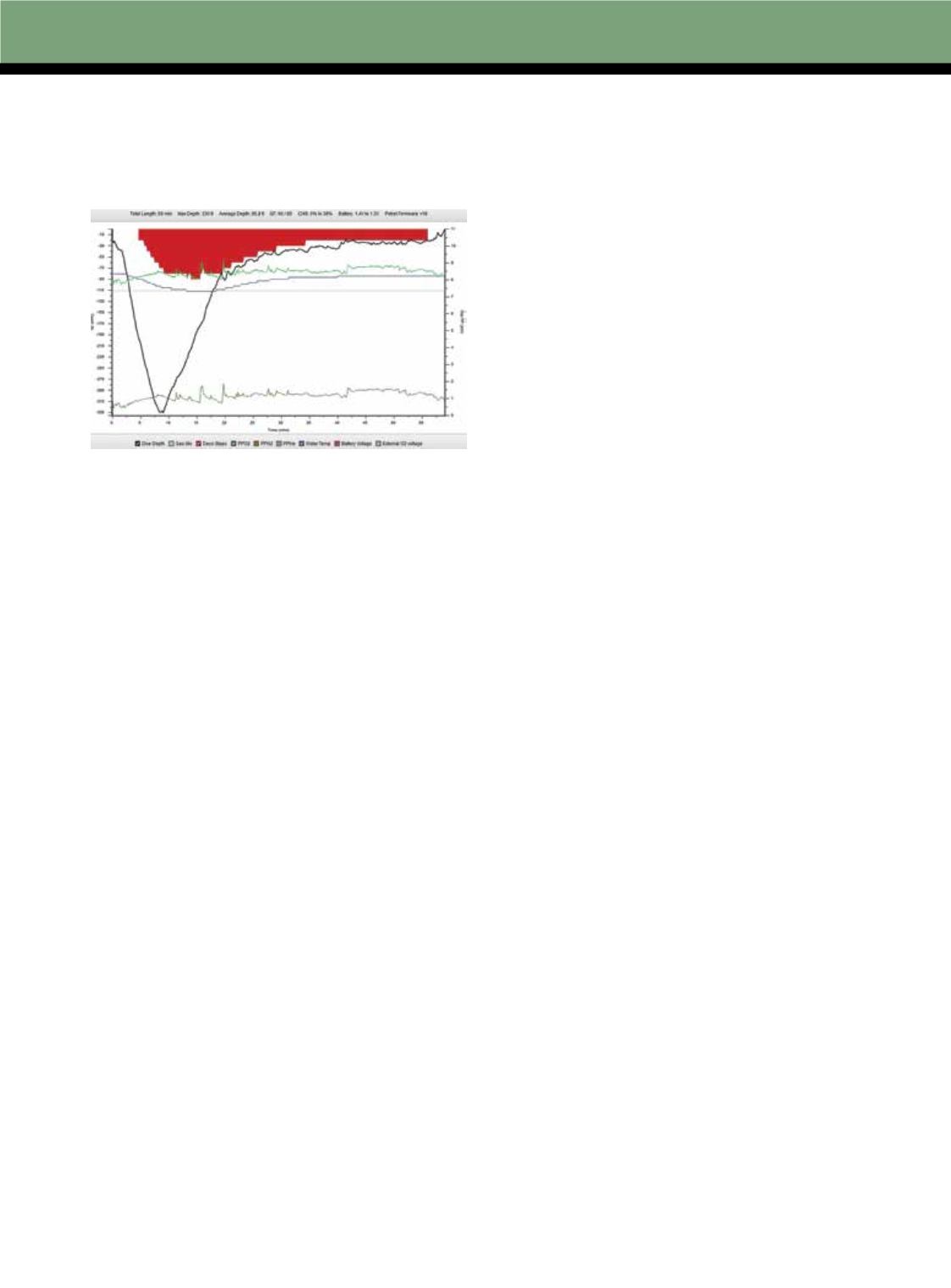

Figure 1 shows the dive profile of a decompression dive

in which the diver completed decompression 10 to 20

feet deeper than the dive computer algorithm required

and then extended the time spent in the relatively

shallow zone after the obligatory stop period before

surfacing. This may be a more conservative ascent

profile than was required, but the worry-free endpoint

is reflected in the absence of bubbles seen in the heart

during postdive monitoring.

There are times when over-applying well-intended

rules can get in the way of safety. For example, divers are

frequently taught to surface with a reserve of 500 psi in

their tanks. If the concern for surfacing with this reserve

becomes so compelling that safety stops are abbreviated,

the rule becomes counterproductive. Dives should be

planned to be finished with a reserve of air, but using some

of that supply to extend a safety stop is probably a high-

benefit compromise. Having said this, any deviations from

established rules should be discussed postdive and actions

should be taken to avoid unnecessary future violations.

Another area in which safety can be put at risk

is reverse dive profiles. If all other things are equal,

planning the deepest dive first makes sense in that it

is consistent with good practice for multilevel diving.

But all things are frequently not equal, and, as far as

we know, the body does not actually register whether

inert gas accumulates at pressure A or pressure B;

the important thing is the total accumulation and the

subsequent pressures achieved to eliminate it from the

body. Practically speaking, the order of the maximum

depth between two dives can be unimportant. Concerns

arise when the “deepest dive first” rule is applied with

such rigor that an unnecessarily deep dive is conducted

for no other reason than to allow a second deep dive

when it must be scheduled later (for example, to meet a

suitable tide state). Mindless fixation on rules can create

problems. Dive planning should be thoughtful.

Surface intervals also need to be considered. There is a

trend toward progressive shortening, probably as a function

of mission creep and perceived efficiency. Surface intervals

are important for inert gas elimination. The minimum

reasonable surface interval will vary with the exposure,

but focusing on the minimum is not conservative

practice. If short surface intervals are necessary, the

severity of the dive profiles should be moderated.

The ends of dive trips often require consideration

of the final surface interval before flying. Flying-after-

diving plans are often based on guidelines produced

at a DAN workshop.

2

The recommended minimum

preflight surface intervals were developed from the

available data: 12 hours after single dives within

no-decompression limits; 18 hours after multiple dives

per day or multiple diving days; and “substantially longer

than 18 hours” after decompression dives. An added

challenge is that these guidelines apply only to aircraft

cabin pressures equivalent to altitudes in the 2,000- to

8,000-foot range. Additional buffers are recommended

since it cannot be known with certainty whether cabin

altitudes might exceed this range. Planning a surface

interval of at least 24 hours following diving is a good

rule of thumb, and an extra safety buffer can be gained

through more conservative exposures on the final day

of diving. Driving to altitude postdive can similarly

induce additional decompression stress; it also requires

appropriate pre-travel surface intervals.

Ultimately, the best way to protect yourself and your

partners is to build conservatism into all aspects of dive

planning and execution. The net effect can be a high

level of safety, often with relatively little compromise

in your diving experience. When good habits are

established and peace of mind maintained, the best

diving in the world is possible. The thoughtful and

well-informed diver remains the most important factor

in producing safe outcomes.

AD

REFERENCES

1. Pollock NW. Gradient Factors: A pathway for controlling decompression risk. Alert Diver 2015; 31(4): 46-9.

2. Sheffield PJ, Vann RD, eds. DAN Flying After Recreational Diving Workshop Proceedings; May 2, 2002. Durham,

NC: Divers Alert Network, 2004.

Figure 1.