102

|

WINTER 2017

WATER

PLANET

T

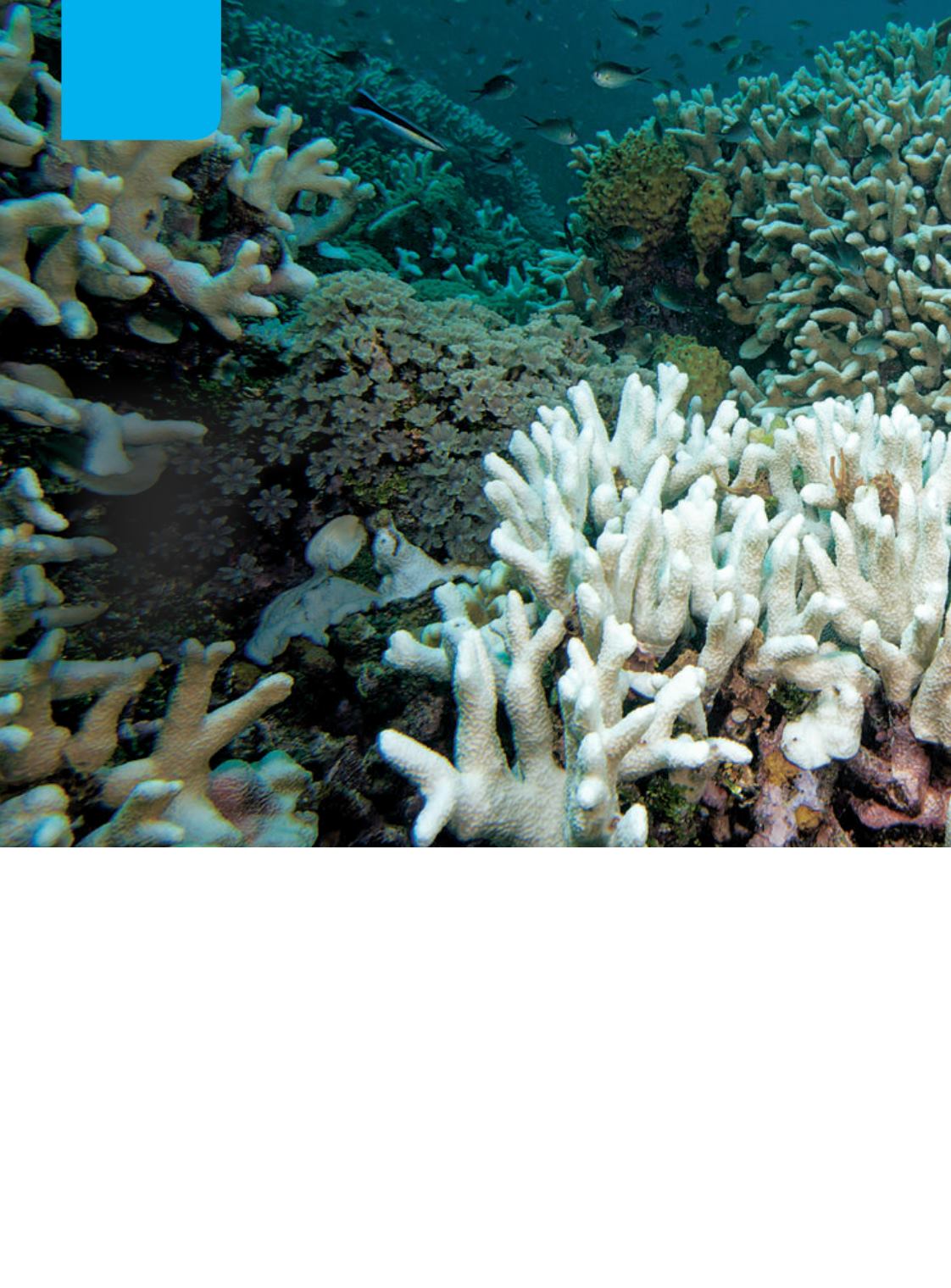

he reports of its death are greatly

exaggerated. Throughout 2016,

news articles, including a widely

read satirical obituary in

Outside

magazine, reported on the demise of

the Great Barrier Reef (GBR). But

the reef is not dead. Although in 2016 it suffered the

most extensive mass bleaching event in its history, it

remains one of the natural wonders of the world. If you

head to Cairns or Townsville, Australia, and jump on

a dive boat, you may not even notice any effects of this

recent bleaching.

Like reefs around the world, the GBR is subject to a

number of stressors, one of the most dominant being

global climate change. If we use the recent bleaching

and mortality events on the GBR as a wake-up call

rather than grieving the loss of something that still

exists, the reef ecosystem can repair itself. To remain

optimistic, it is important to understand the difference

between coral bleaching and coral mortality.

Throughout the GBR bleaching event, scientists

from the Australian Research Council (ARC) Centre

of Excellence for Coral Reef Studies (Coral CoE) at

James Cook University, the Great Barrier Reef Marine

Park Authority (GBRMPA), the Australian Institute of

Marine Science (AIMS) and other partners performed

aerial and extensive underwater surveys on reefs

stretching the GBR’s entirety. Surveys were conducted

in March and April 2016 when bleaching was at

its worst (March and April are among the months

with the highest ocean temperatures in the southern

hemisphere) and again on the same reefs in October

DIFFERENTIATING

CORAL BLEACHING

AND CORAL

MORTALITY

By Sarah Egner

A CASE STUDY FROM THE

GREAT BARRIER REEF