slackers; larval fish are small, fast, erratic and tricky to

track down in a featureless ocean. But when you find a

jaw-dropping and possibly never-before-photographed

animal, the thrill is as exhilarating as hooking a giant

sailfish — although the “sailfish” we find in our watery

fairyland can fit in the palm of your hand.

In less than 10 minutes Anna is spotlighting a larval

flounder that was drawn to her handlight like a moth

to a flame. Not knowing its behavior, I hold back and

watch one of the fanciest fish I’ve ever seen flutter in her

beam before flopping onto its side like a dead leaf. As I

inch closer, the fish rights itself and sails away. I’m close

behind, attempting to work my way alongside, focusing,

framing and hoping it will slow or turn back on itself.

Unsure how far I’ve traveled, I glance around, locate the

down line and turn back. The fish is gone.

I spiral, sweeping my light in a circle. Somehow

the beam catches a flicker of fins heading toward the

surface. I’m after it and only catch up when the fish

comes to a halt indignantly facing in the opposite

direction. I slip to its left, but the fish slips right. I pivot

right, it tacks left, flashing its tail in my face as it speeds

away. In fits and starts the chase continues until the

larva slows, makes an about face and swims toward me

at a leisurely pace. “Steady, steady,” I coach myself as the

flounder passes within a hand’s width, fins flying.

All it took was that one outrageous larval fish, and

Anna and I are hooked just like our South Florida

colleagues, who seldom, if ever, miss a scheduled night

drift. The majority are veteran Blue Heron Bridge

shooters — naturalists to the core and well-versed in the

trials and rewards of wildlife photography. As a group

they have taken to night drifts like ducks to water, but

they were not the first to fall under the spell of offshore

larvae. By the time the Florida folks made their first drift

two years ago, divers in Hawaii had been photographing

larval fish at night for 20 years. Inspired by legendary

underwater photographer Chris Newbert, their night

drifts, known in the islands as blackwater diving,

introduced larval art to the world. Our Florida friends

are happily carrying on the tradition 5,000 miles away.

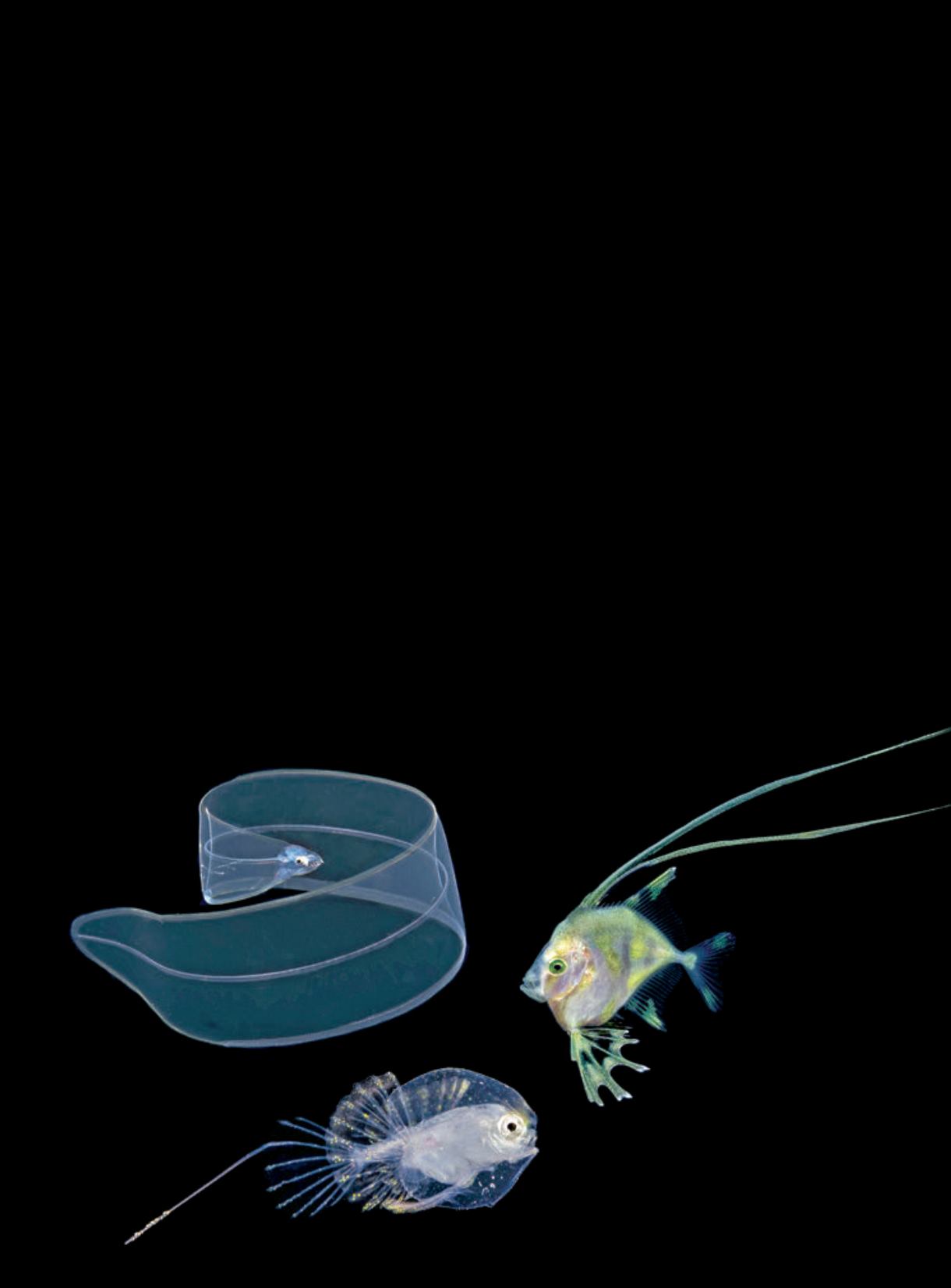

Back on board, the boat is buzzing. Images of

unfamiliar animals attract the biggest crowds around

glowing camera screens. As you might expect, “What

is it?” is the most frequently asked question in a world

where crabs don’t look like crabs, and fish appear as

illusions. Photos of unidentified animals are forwarded

to two gentlemen half a world away who acquired their

taxonomic expertise cataloguing morphological sketches

of specimens swept up in plankton tows.

Scientific understanding of the oceanic orphanage

has been transformed in the past 15 years. It is no

longer thought to be an exclusively open system,

randomly transporting passive larvae to distant shores.

Recent studies have shown larval fishes to be strong

swimmers with sophisticated instincts for remaining

in local waters. But exactly where they go between

spawning and settlement remains a mystery. Meanwhile,

underwater photographers from Florida, Hawaii and

beyond are adding bits of understanding to the sea of

knowledge whose currents sweep us all along like night

drifters, having the time of our lives.

AD

ALERTDIVER.COM|

35

CLOCKWISE FROM LEFT: STEVEN KOVACS, SUSAN MEARS, DEBORAH DEVERS