50

|

FALL 2013

confident it’s in working order; dive within the limits of

his training, ability and comfort level; adhere to generally

accepted safe diving practices; adhere to the dive briefings

and, unless expressly agreed upon otherwise, dive with a

buddy. The diver must be familiar with the skill level and

equipment of his buddy, and there should be an agreed-

upon dive plan.

When is it OK for an operator to deny a diver service?

Steidley:

It is appropriate for an operator to deny service

any time a diver demonstrates unsafe diving practices.

Concannon:

The operator should deny service to a diver

whenever the operator reasonably believes the diver will be a

danger to himself or others. The operator is better off losing

a customer than a life. I would rather defend the rare case

where a disgruntled diver is suing an operator for failing

to provide service than the more common case where a

disgruntled family is suing because the operator lost a diver

who they allowed to dive despite safety concerns.

Hewitt:

A dive operator may deny a diver the opportunity to

dive when the operator objectively and reasonably believes

the diver poses a danger to himself or his fellow divers. The

dive operator cannot deny service on a discriminatory basis.

The consequence of denying service to a diver is that the

dive operator may face a breach of contract claim if money

is accepted in consideration for the dive trip. Such a claim is

highly unlikely (especially when any monetary consideration

is returned to the diver). The risk of the dive operator losing

a customer is far outweighed by the risk of a lawsuit due to

injury of the diver or others. The general consensus of the

lawyers defending scuba-diving cases is that it is better for

the dive operator to err on the side of caution and avoid

unnecessary risks.

What do you consider to be landmark

liability cases in the dive community?

Why?

Hewitt:

In recent years, there have

been three landmark scuba diving cases.

The first, Barrett v. Ambient Pressure

Diving, involved a death related to the

use of a rebreather. In the trial, the jury

acknowledged the risks associated with

technical diving and readily placed

the responsibility on the diver for fully

understanding the equipment, ensuring

it was working properly and using the

equipment correctly during the dive.

They did not hold the manufacturer to

higher safety standards such as those of

automobile or lawnmower manufacturers.

The second, Carlock v. M/V Sundiver,

involved a dive boat leaving a diver at the dive site. The

court ruled that such an incident was not within the scope

of the waiver and release and was not an inherent risk of

scuba diving. The jury determined that every one of the dive

professionals involved had responsibility for the incident.

While the jurors believed the adrift diver had some fault for

failing to adhere to the buddy system and the dive briefing,

they found it relatively minor in comparison to the fault of

the professionals.

The third case, Goetz v. Horizon Charters, involved a

claim of negligent rescue in which two divers became

separated, and more than 30 minutes passed before a

search was initiated to locate the missing diver. The court

ruled that the family of the deceased diver must establish

gross negligence, because the waiver and release signed

by the decedent barred the ordinary negligence claim.

In a precedent-setting decision, the court decided that a

redacted version of the release could be shown to the jury

to demonstrate the deceased diver’s agreement to adhere

to safe diving practices (i.e., buddy-diving procedures). The

case also highlighted the family’s inability to rule out the

possibility that the diver’s underlying health condition played

a role in the death and underscored the coroner’s limited

ability to determine the cause of the drowning.

RESEARCH, EDUCATION & MEDICINE

//

E X P E R T O P I N I O N S

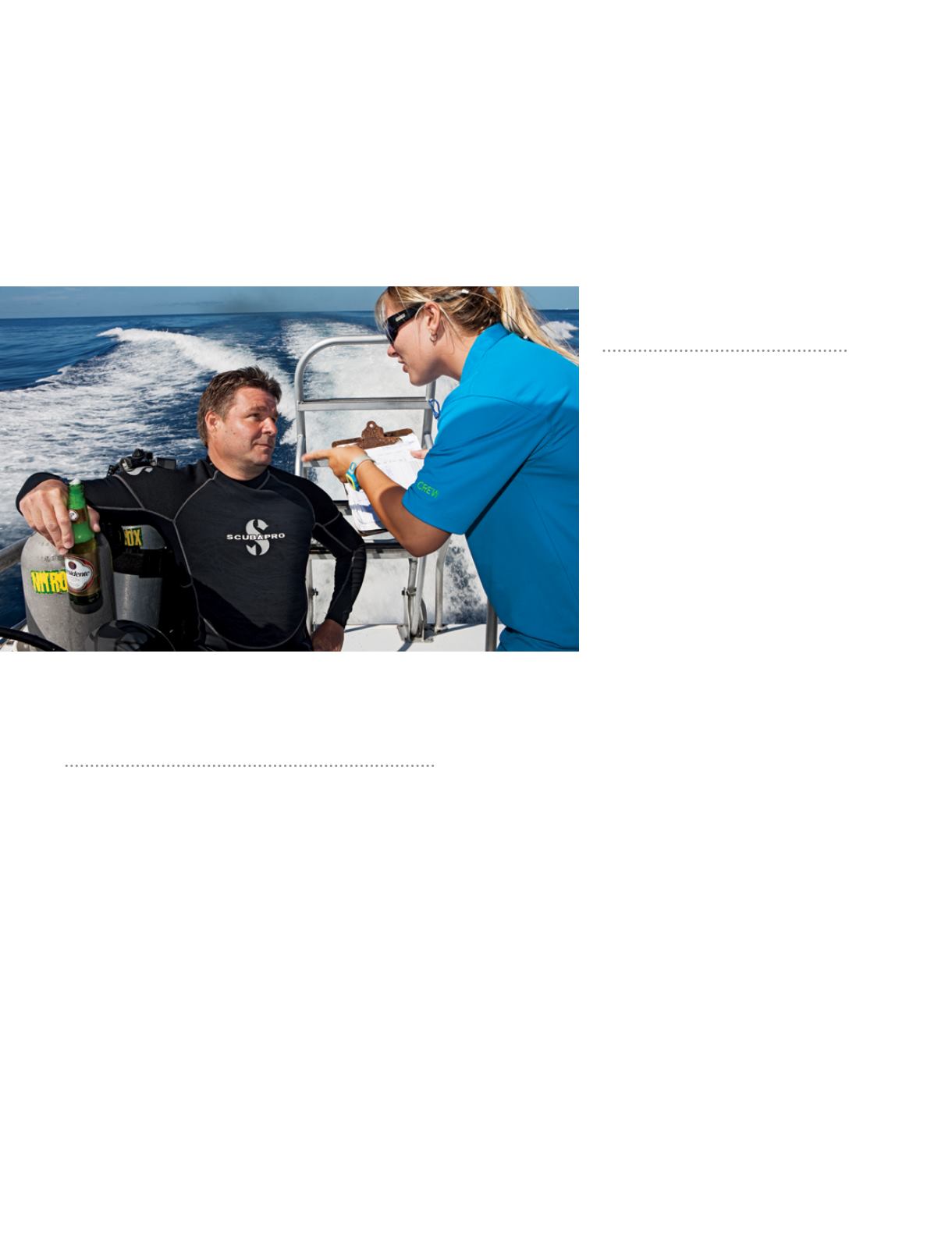

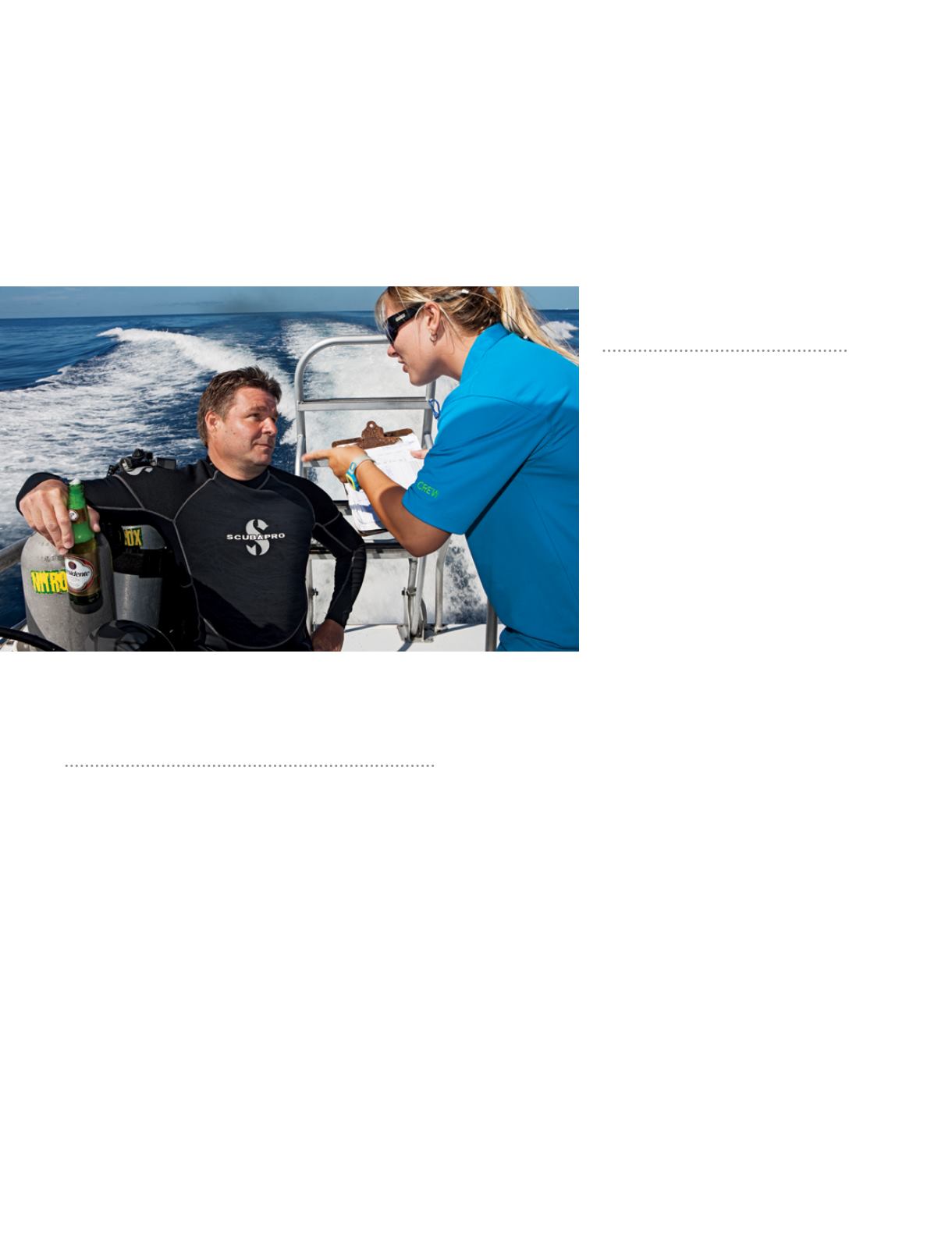

Dive operators may deny service to divers who they believe will be a

danger to themselves or other divers.