T

he sun was out, and the visibility

down at 30 feet was excellent. It was

nearly time to ascend, so my buddy

tapped her watch and then gave me

the “OK” signal; I happily signaled

back. This down time was just what I

had needed after a busy week at work.

Then, just when everything was going perfectly, I

heard some bubbling. I removed my second stage from

my mouth and held it with the mouthpiece facing

downward. To my dismay, I saw bubbles coming out

— my regulator was leaking. We were almost at our

safety stop, so I put the regulator back in my mouth

and double-checked that my buddy was within reach in

case something unexpected happened. Thinking about

it, I realized I hadn’t had my regulator serviced since

last summer, so I resolved to drop it off at the dive

shop later in the week. Better safe than sorry when it

comes to having gas to breathe.

When I got back to work at DAN®, my first task

for the week was to look at the latest diving incident

reports, which are submitted by divers who have had

or have witnessed a near-miss. These are unexpected

events that could have resulted in an injury. Curious,

I counted how many of the incidents were the result

of equipment malfunctions. Of the first 92 reports I

reviewed, 16 incidents (17 percent) involved equipment

issues. Based on other data, we know this number likely

overrepresents the incidence of equipment problems,

but this overrepresentation stands to reason because

equipment failure is a matter of concern to many divers. I

found it interesting that 13 of the 16 equipment problems

reported (81 percent) related to air supply, and the other

three reports (19 percent) related to buoyancy control.

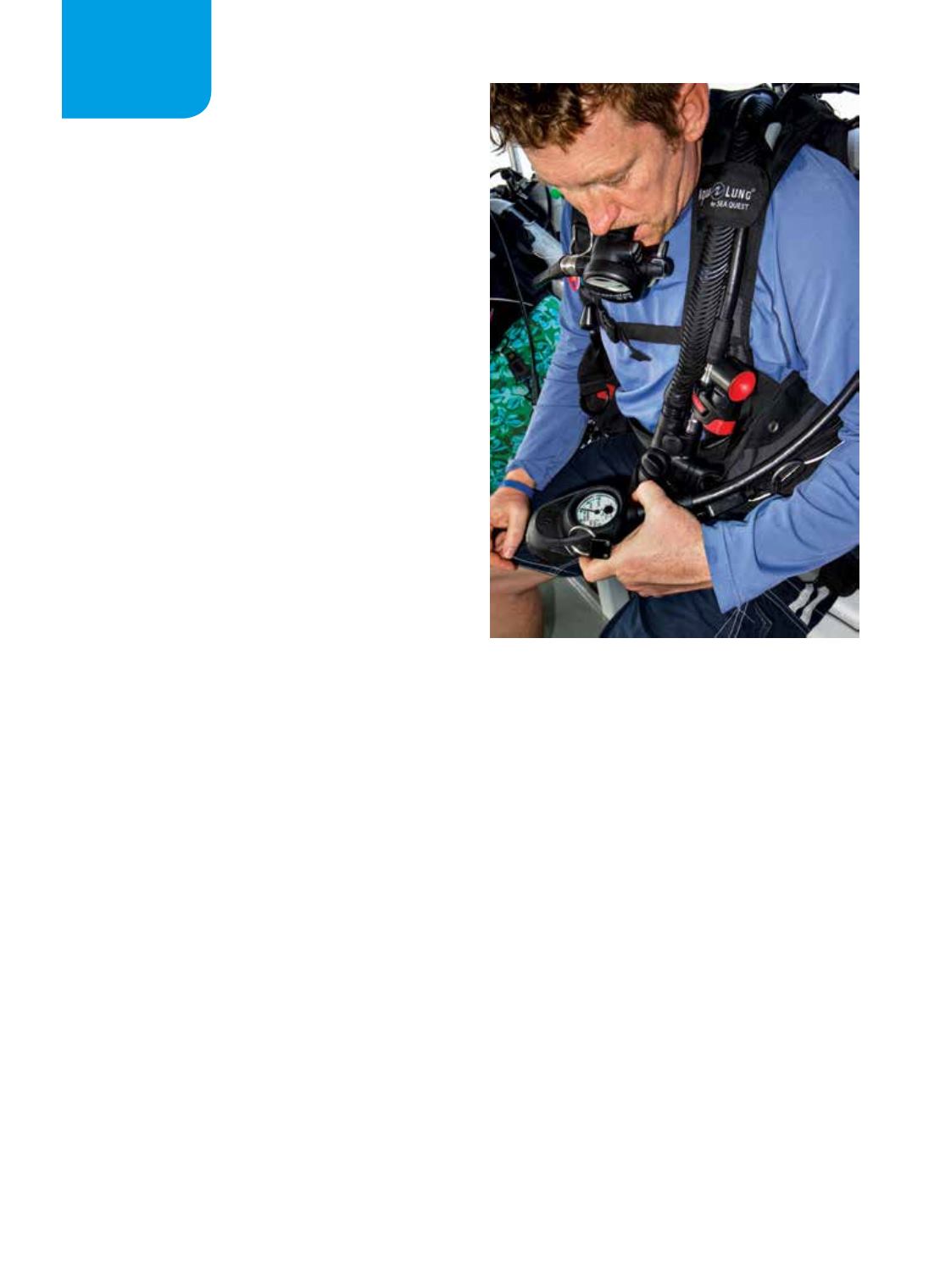

While studying the air-supply problems, I soon

identified a common error: failure to watch the

submersible pressure gauge (SPG) while test-breathing

the regulator. Here is an excerpt from one of the

incident reports:

The group went out with four divers and two

guides. The drop-in was a back roll, and I dropped

in first. Prior to entry I checked all my gear and

tested my regulator and inflator. I then dumped

the air from my BCD [buoyancy control device]

and moved into position. The deckhand checked

all my equipment and made sure my tank valve

was opened. I rolled in and dropped down 6-10

feet and took my first breath: nothing. Now I was

underwater, slightly negatively buoyant, with no air

for breathing or inflation. I kicked for all I had and

was able to reach the boat and grab ahold of the

swim deck. The deckhand was then able to reach

over and turn my air back on

.

Another incident report highlights a common error

that’s reported to DAN every year: turning the valve

the wrong way.

While diving in Florida, I noticed that upon each

inhalation the needle of my SPG fluctuated. It dipped

down with each breath before returning to the correct

pressure reading for my tank. I continued diving while

keeping a close eye on the gauge, and upon reaching

a depth of approximately 55 feet it suddenly became

very difficult for me to breathe. I looked at my SPG

mid-breath and saw the needle drop to 0 psi, and it

did not readily move back up. I felt like there was no

more air available to me even though I knew there

108

|

SPRING 2016

GEAR

GEAR-RELATED

INCIDENTS

By Peter Buzzacott, MPH, Ph.D.

STEPHEN FRINK