78

|

FALL 2014

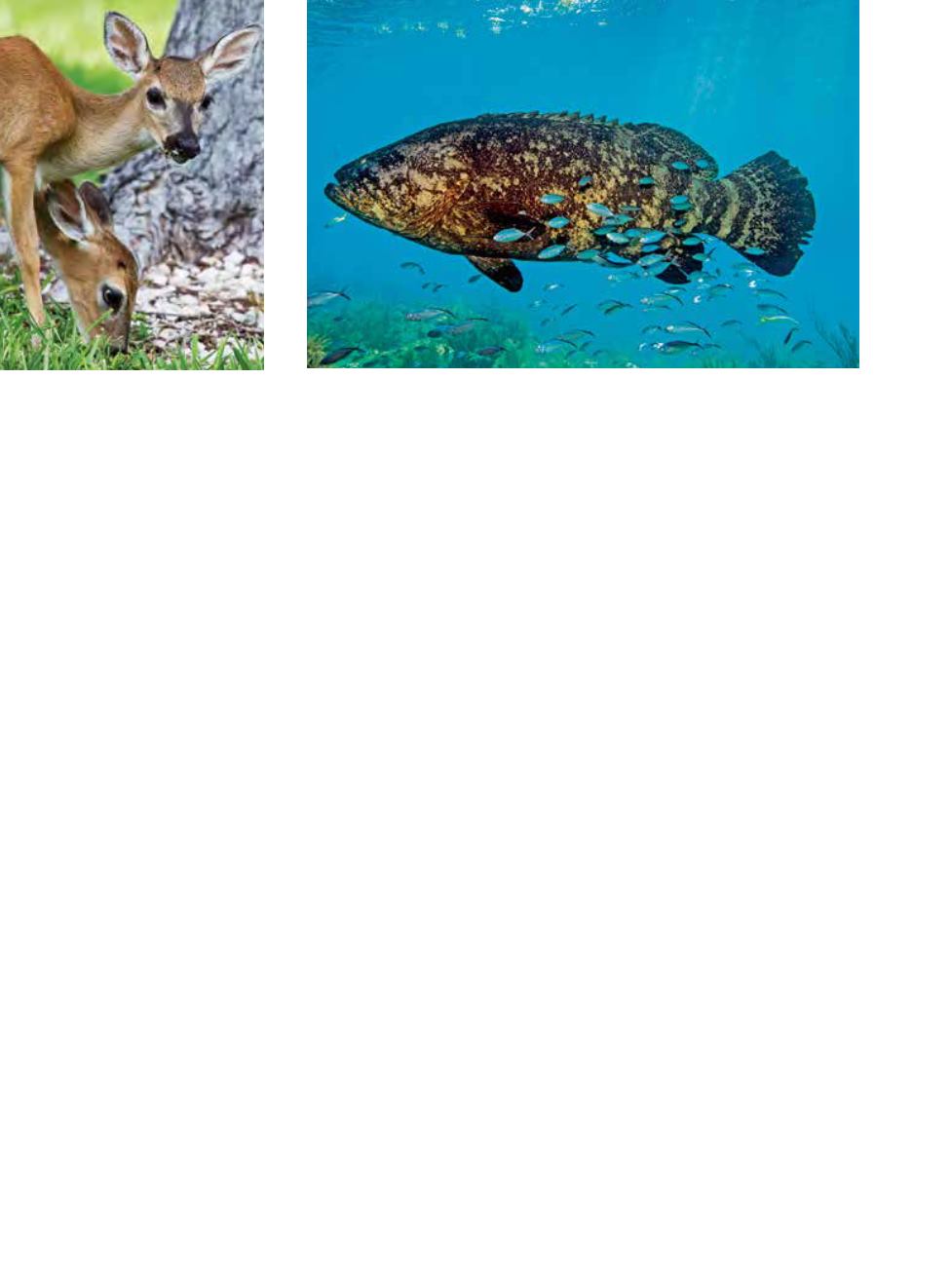

ball of silversides attempting to hide inside the bow.

Predators are everywhere, fat, happy and toying with

the million-minnow meal at their leisure. At least two

dozen black groupers lurk in the shadows, ambushing

the minnows from below while bar jacks and yellowtails

strike from above. The frenzy has everything agitated;

even green morays are swimming in the open. When

I finally climb back aboard, Anna and Quinn are still

talking about their adventure.

“Tell Papa what you saw, Quinn.”

“A manta,” he chirps with a grin as big as the Benwood.

“Where?” I ask, a bit uncertain he actually made such

a rare sighting.

“Off the bow, not far from where you were

photographing the minnows,” Quinn replies. “I

pointed it out to my instructor and the lady with us.

They saw it, too.”

“Can you believe it?” Anna adds as she switches tanks.

“That’s some impressive fish to add to your list.”

To help Quinn become acquainted with the wildlife,

we suggested that he write down the names of fish

species he sees during the trip. Counting the manta,

he added six new names to the list on the Benwood

including the green morays, tarpon and, of course, the

gang of well-fed black grouper. We’ve also scheduled

several shore visits during our stay to learn about other

facets of the underwater world and to become familiar

what is being done to protect marine creatures and

the environment.

AN UNDERWATER HOTEL

That afternoon we pull into a parking area next to a

mangrove lagoon, the home of the

Jules’ Undersea

Lodge

, for a tour of the world’s only underwater hotel.

The submerged habitat, which can sleep six aquanauts,

started its operational life in the early 1970s perched on a

60-foot sand shelf off Puerto Rico, where it served as one

of the earliest underwater research labs. Quinn and I slip

on scuba tanks and navigate a circuitous route across the

lagoon. Waylaid by a contingent of shallow-water fish,

we arrive late, but we add five more species to the list.

For decades I’ve heard about the exploits of aquanauts

living beneath the sea, occasionally for months at a

time. Even with all my reading I had no sense of the

intrigue involved until I popped up through the moon

pool inside the habitat’s wet room. This and the three

attached rooms, kept from flooding by a constant flow

of compressed air, are stark but well appointed. A pair

of round 42-inch windows dominates the space with a

warm yellow-green glow and views of passing fish.

SEVEN MILES OF BRIDGE

The following morning we leave Key Largo early for

a 77-mile drive to Big Pine Key — the home of

Looe

Key Reef

and a gem of a place to dive. Our two-hour

drive carries us over much of the Overseas Highway

— a destination in its own right. At the start, along the

upper Keys, the sea is nowhere to be seen, but as we

continue southwest the bridges separating the Atlantic

from Florida Bay become longer and longer until soon

we’re surrounded by water. Bridge after bridge crosses

a balmy blue world punctuated with boats and islands.

By the time we reach the famous Seven-Mile Bridge on

the south end of Marathon, it is easy to believe that the

Earth’s surface really is seven-tenths water.

The Seven-Mile Bridge runs parallel to an old railroad

trestle — a remnant of the first land connection between

the mainland and Key West. The ocean-going extension

of the Florida East Coast Railway, dubbed “Flagler’s Folly”

at the expense of tycoon Henry Flagler, who single-

handedly financed the ill-fated enterprise, laid its first

track in 1905. Completed in 1912, trains ran the line for

22 unprofitable years before receiving a knockout blow

from the Labor Day Hurricane of 1935. With no appetite