86

|

FALL 2014

Capturing a sea turtle on a dive is an amazing

experience, but volunteer divers at Cocos can do as

much or little of the scientific work as they want.

Stabb, who considers himself a hands-on person, tries

to do everything, but he also recognizes the value of

volunteers who choose to observe: “I’ve seen plenty

of people who come and are happy just to watch, and

Todd [Steiner] is happy to have them. Having people

along is effectively funding the research.”

For volunteers at Cocos, the opportunities to

engage in a variety of tasks are many. Nonie Silver, a

Washington, D.C., business owner and participant on

many of the Cocos Island expeditions, says she often

serves as the logistics person: “The shark tags need

to be prepped and tasks defined for each of the dives,

whether we’re retrieving receivers, catching turtles or

tagging sharks. For example, when we catch a turtle,

there are a series of steps that need to be completed

before the turtle can be released back to the sea.

“It makes you feel good that you’re doing something to

help,” Silver continues. “In other places you see the lack

of fish or coral, and it makes you appreciate the fact that

this one little thing you’re doing may help the ocean.”

Volunteers can also help by taking photographs; the

researchers maintain a photo identification library in

cooperation with local dive operators. These photos,

Steiner explains, help him track individual animals even

when he isn’t there in person.

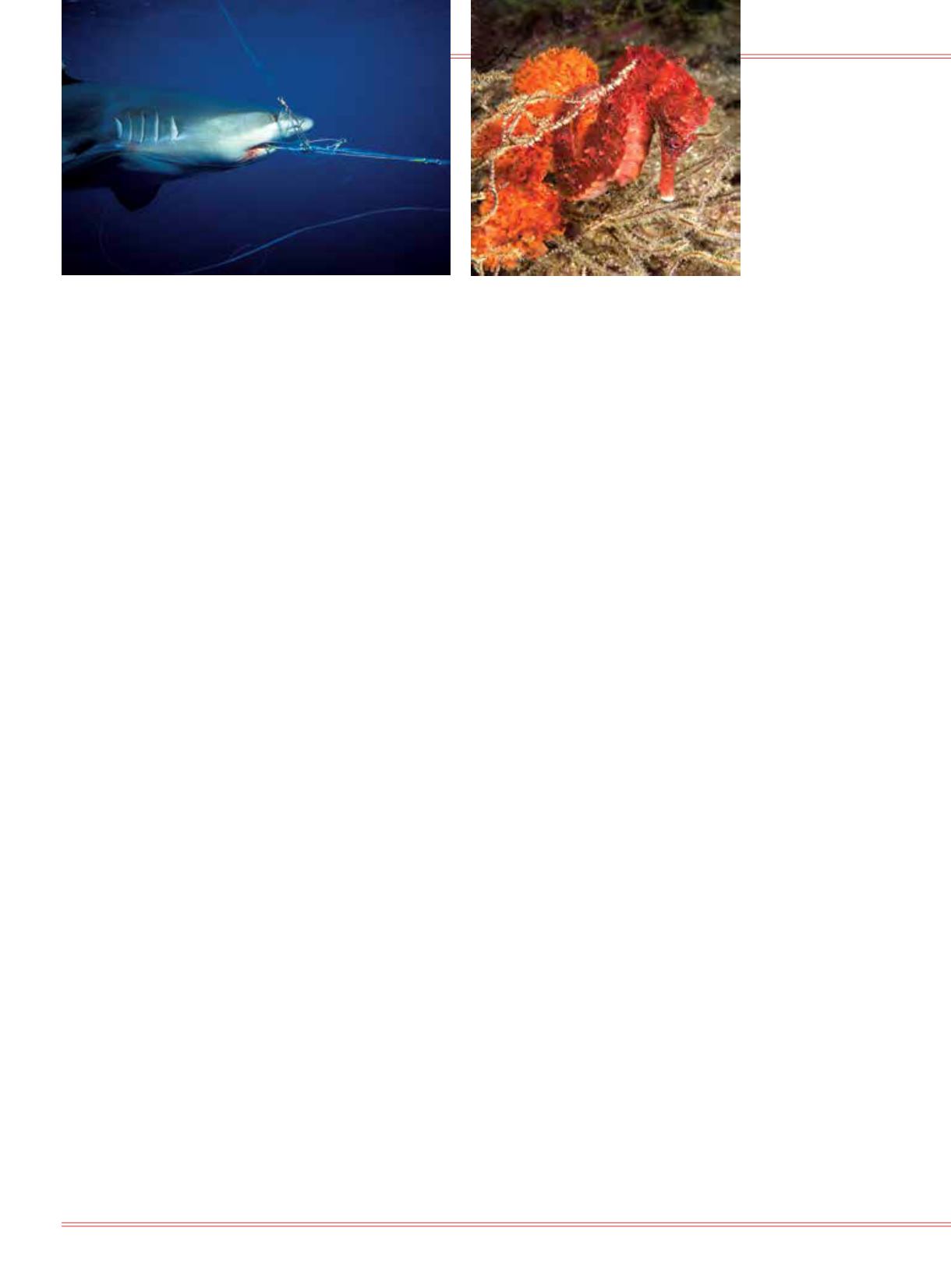

Tagging sharks is a bit trickier because it involves using

a spear to inject a tag at a specific point on the shark’s

body. The Cocos Island National Park’s rules require that

volunteers who would like to help with this task have a

scientific background and relevant experience, but anyone

can help count sharks and rays, which is an important

element of documenting population trends. For these

jobs, divers receive instruction in species identification

and survey techniques and then use an underwater slate

to record location, time and depth at five-minute intervals

for each species they spot. Still other volunteers remain

on the boat and record this data on computers.

Cocos Island provides only one of the many

opportunities to contribute to marine science and

conservation work. In other locations, the Reef

Environmental Education Foundation (REEF) asks

volunteers to help cull the increasing numbers of

invasive lionfish prowling their favorite dive sites. The

organization is documenting the consequences of the

lionfish invasion in hopes of ultimately minimizing its

effect on native fish populations. Under the direction of

Lad Akins, REEF director of special projects, and Peter

Hughes, founder of DivEncounters Alliance, up to 20

divers at a time can participate in lionfish collection and

dissection in addition to reef fish surveys.

Pam and Terry Hillegas of Englewood, Colo., have

taken six REEF lionfish trips to various locations and

say that their trips have made them more aware of

the ways that invasive species can affect the ocean.

According to Terry, the service and educational aspects

of the trip added an enormous amount of value to his

experience: “That really made the whole experience

more interesting for us. I feel like I’m doing something

beneficial and not just enjoying recreational diving.”

“Lad and Peter are very knowledgeable and show you

how to correctly handle lionfish so you don’t have any

mishaps,” Pam adds. “It’s amazing how comfortable

they can make you feel handling these fish.” Those who

are interested in taking these expeditions but don’t care

to spear or bag lionfish can also do surveys to count the

lionfish and the other species on individual reefs.

Organizations such as REEF have a larger effect on

the environment than one might think. “I dive quite a

bit in the Caribbean and realize the damage that lionfish

do,” says Calvin Roggow, a volunteer from Oklahoma.

“REEF seems to be at the forefront of actively trying

to control them. We go back because the trips are so

enjoyable; it’s really a great time, and you’re doing a

good thing for the ocean.”

For divers looking to travel a bit farther afield,

Projects Abroad offers two land-based volunteer

diving projects in Southeast Asia — one in Cambodia

and the other in Thailand.

On the Cambodian island of Koh Rong Samloem, a

two-hour boat ride from the coast, divers help survey

marine habitats as well as coral and fish diversity,

From left: Longline

fishing is efficient and

destructive. Apex preda-

tors like sharks are

particularly susceptible.

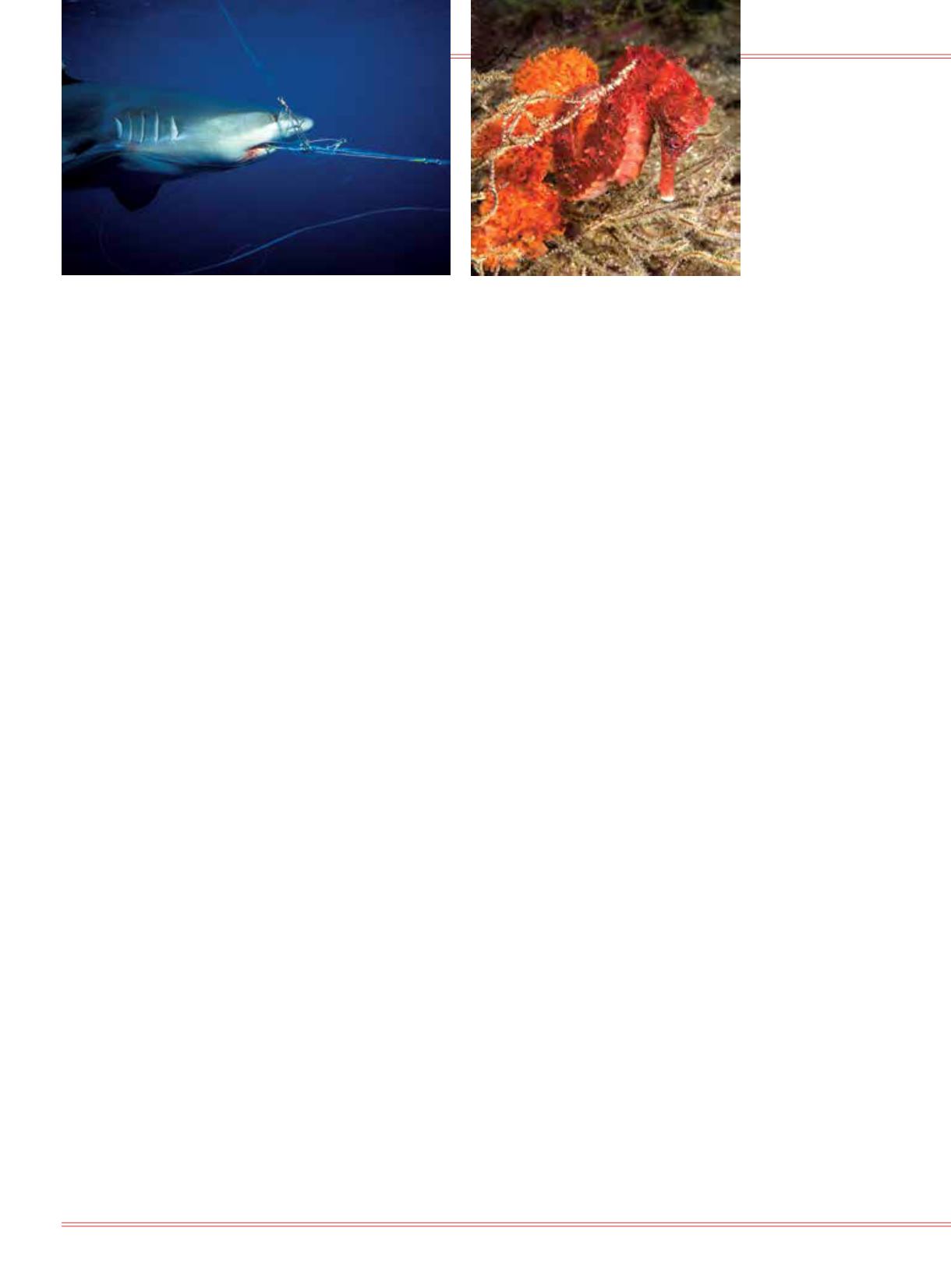

The Seahorse Trust uses

volunteer divers to help

them protect seahorses,

150 million of which

are taken from the wild

each year for traditional

Chinese medicine.

STEPHEN FRINK

STEPHEN FRINK