|

79

to rebuild, what remained of the railway was sold to the

state. Following a bit of creative thinking, a two-lane

asphalt road was built on top the existing trestles 15 feet

above the old tracks, making it possible for automobiles

to drive all the way to Key West for the first time.

We arrive at Big Pine Key, the gateway to the lower

Keys and just 22 miles from Key West, at 7 a.m., too early

to check in at the dive shop, so we go hunting for deer

— Key deer to be exact, the islands’ miniature version of

whitetails, not much larger than Irish setters. We follow

Anna’s GPS to a suburban crossroads where they are

reported to hang out. And sure enough we spot three

does and a fawn nibbling grass by the road. Quinn lowers

his window and takes a photo.

The high-profile spur-and-groove reef inside Looe

Key National Marine Sanctuary has long been one of my

favorite dives. Even though fishing is allowed, wire traps,

spearfishing and fish collecting have been banned for

three decades, allowing the marine life to grow large and

plentiful. Almost before the bubbles clear Quinn becomes

part of a parrotfish school passing under the boat. A

diver-friendly angelfish nips the bubbles about his head as

he kneels on the sand. Around a bend he sees a reef shark

in the distance. He swims after it to get a better look — a

good sign. Even more surprising, a 5-foot, 450-pound

Goliath grouper makes a slow pass — a beneficiary of

1990 legislation protecting the species. An encounter

with such a large fish would have been unheard of four

decades ago when I first dived the Keys.

KEY WEST AND THE VANDENBERG

We arrive in Key West mid-morning and stop at the new

Florida Keys Eco-Discovery Center. The state-of-the-art

educational center offers an opportunity to learn about

the area’s wildlife, habitats and conservation efforts — a

message we want Quinn to hear. We begin by learning

about the Florida Keys National Marine Sanctuary

(FKNMS), which is one of 14 underwater parks

managed by the National Oceanic and Atmospheric

Administration (NOAA). The FKNMS, established in

1992, covers nearly 4,000 square miles from south of

Miami to the Dry Tortugas (an additional 70 miles by sea

from Key West). Two previously established preserves,

the Key Largo National Marine Sanctuary and the Looe

Key National Marine Sanctuary, were enveloped by the

larger and more empowered FKNMS.

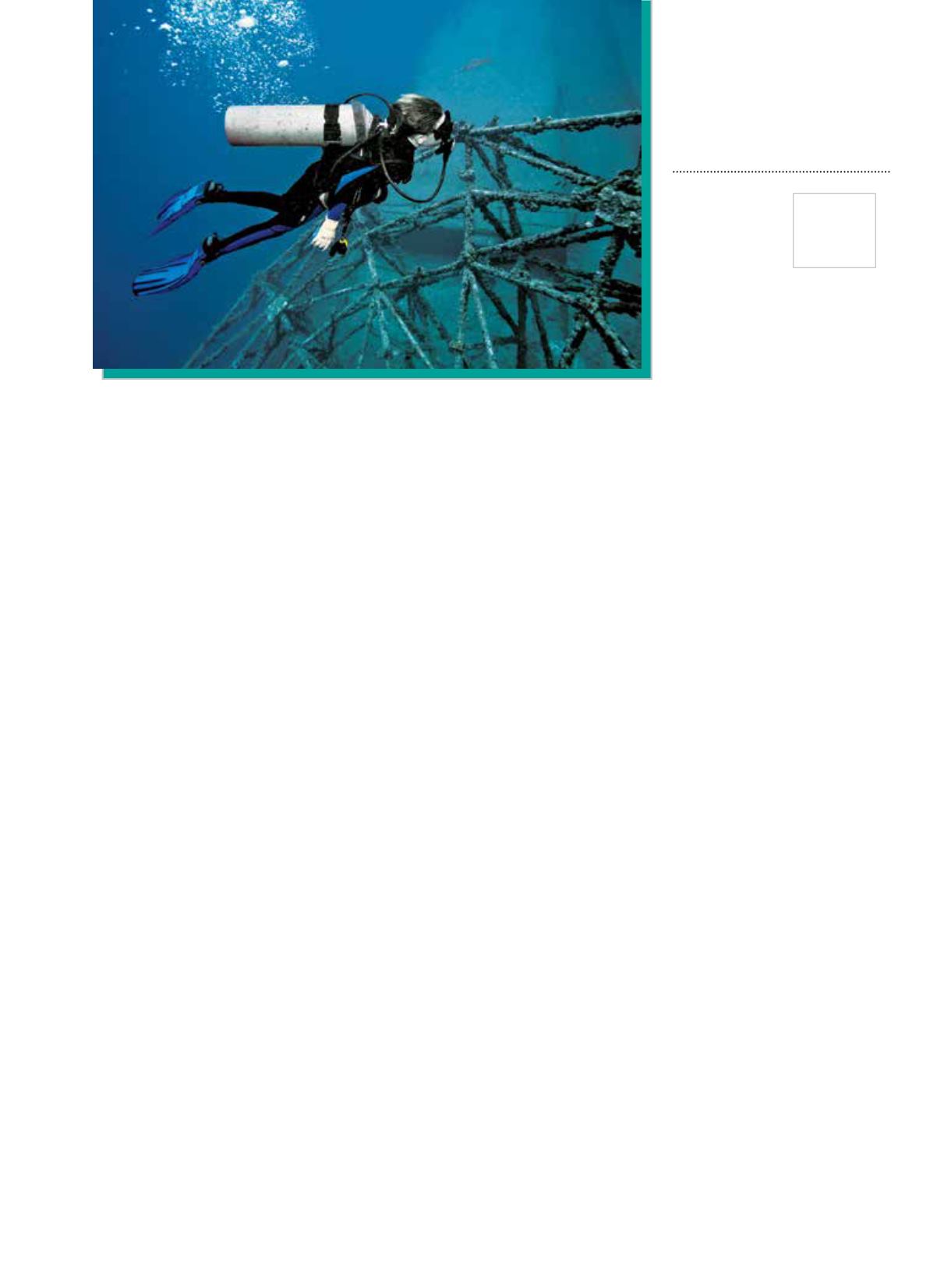

These days diving Key West almost has to include

a visit to the

USS Vandenberg

, a 523-foot missile-

tracking vessel that now towers 10 stories off a 140-foot

hardpan bottom seven miles south of Key West. Since its

deployment in 2009 as an artificial reef, the massive ship

has attracted divers and fish by the tens of thousands.

With his new advanced certification and by diving with

an instructor, Quinn is allowed to explore the vessel’s

superstructure that rises to within 50 feet of the surface.

Our only worry is current, which occasionally sweeps

the Vandenberg with significant force.

Quinn’s luck keeps running. On the morning we

arrive at the site along with a boatload of volunteer

fish surveyors from the Reef Environmental Education

Foundation (REEF), barely a ripple stirs around the

mooring line, and visibility hovers near 80 feet. The

Vandenberg seems to go on forever, even after a

20-minute trek from radar dishes to stacks, kingpost

and masts with crow’s nests attached, we are only able

to take in half of the sights. As a bonus, an immense

30- by 40-foot American flag was attached to the

forward antenna mount on July 4. It usually blows with

the currents, but now in the calm it cascades down in

billowing folds of red, white and blue.

Observing the fishwatchers in action made the idea of

fish identification even more appealing. The surveyors

made up of staff, interns and volunteers are monitoring

the Vandenberg as part of a multiple-year fish-

A M E R I C A ’ S

R

E

E F

From far left: Key deer feed at Big

Pine Key. A resident goliath grouper

of Looe Key reef parades past with an

entourage of bar jacks. Quinn swims

over one of the two giant radar dishes

on the Vandenberg.