40

|

FALL 2016

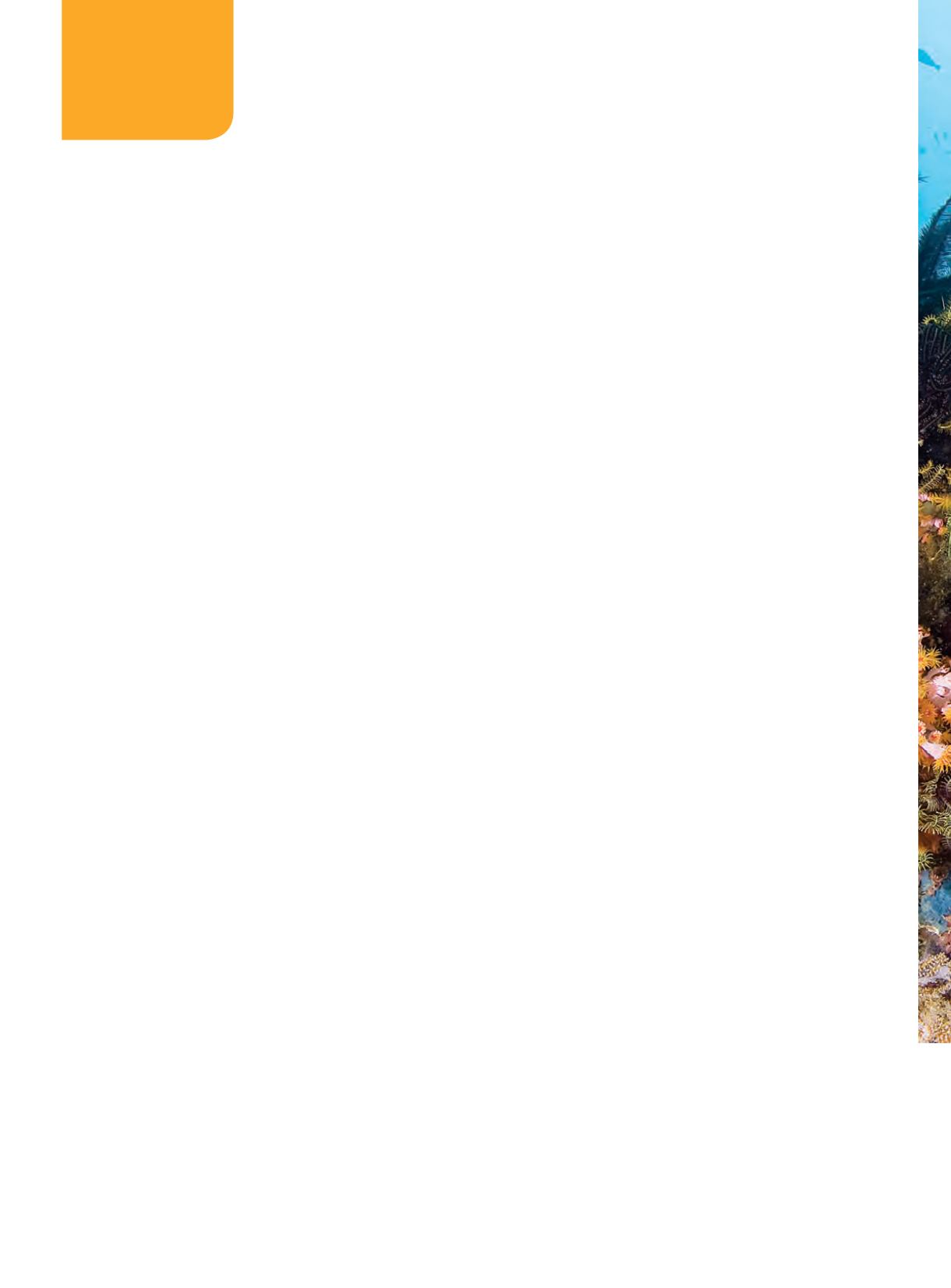

LIFE

AQUATIC

M

ore marine organisms live

on Indo-West Pacific (IWP)

reefs than anywhere else on

Earth. The IWP region covers

a significant portion of the

planet’s surface, ranging from

the shores of eastern Africa across the Indian Ocean,

the Andaman Sea, the Philippine Sea and much of

the tropical Pacific. Within this immense zone lies a

unique hub called the Indo-Malayan Triangle, also

known as the Coral Triangle. Covering 2 million

square miles of ocean, the Coral Triangle includes

the diving utopias of the Philippines, Indonesia,

Malaysia, New Guinea and the Solomon Islands,

and it’s where underwater biological diversity

reaches its zenith.

Divers travel the globe to submerge in places such as

the clear and colorful Caribbean, New England’s shark-

filled seas, the eastern Pacific’s sinuous kelp forests and

the dazzling reefs of the Coral Triangle. Each body of

water, each coast and each island, no matter where

in the world it lies, has its own particular community

of life. This diversity keeps divers roaming from one

destination to the next. But what underlies regional

differences in marine biodiversity? And why does

the Coral Triangle support so much underwater life

compared to any other place on Earth?

SOMEWHERE WARM

For millennia, warm waters have bathed the

Coral Triangle’s flourishing reefs with virtually

no seasonal temperature variation. Warmth and

just the right amount of nutrients allow corals to

effectively outcompete algae for space and sunlight,

thus providing shelter for innumerable fish and

invertebrates. Sea temperature is a major reason for

latitudinal variation in diversity of marine life. There

is longitudinal variation as well; marine life is generally

more concentrated on the western sides of both the

Atlantic and Pacific Oceans. In a nutshell, this has to

do with oceanic current circulation. Cold, nutrient-

filled upwellings generally occur on the eastern sides

of these bodies of water, while the western sides have

fairly clear, balmy waters.

In temperate seas, where algae outgrow corals,

organisms must be able to handle seasonal swings

in temperature and food sources. Temperate and

polar species tend to be ecological generalists, while

tropical species can become specialists due to constant

temperatures, primary production and plentiful food.

Specialization in the tropics leads to a profusion of

symbioses. A dive on any healthy IWP reef will reveal

dozens of commensal associations: anemonefish living

with host anemones, shrimp and gobies, squat lobsters

dependent on crinoids for food and shelter, cleaner

wrasse ridding fishes of parasites, remoras hitching

rides on sharks, and the list goes on.

A CHANGING SEASCAPE

Another factor underpinning the mind-boggling

diversity of life in the Coral Triangle lies deep in the

past, when sharks were much larger and humans were

just a twinkle in the eyes of our primate ancestors.

The land and seascape of the Coral Triangle looked

very different 50 million years ago, when what are now

islands of the southern Philippines, Indonesia, Malaysia

and New Guinea were more widely spread across four

different tectonic plates. Since that time the Pacific,

Indian-Australian, Philippine and Eurasian plates

have been thrust together, forming the convoluted

conglomeration of thousands of islands and reefs

that is the Coral Triangle. Fish and invertebrates

that evolved in separate habitats, originally far from

one another, have amassed in what is known as a

biogeographic sink. The great number and diversity of

marine habitats and environmental conditions make

for an area that attracts species.

The Coral Triangle can be viewed not only as a place

where species have aggregated but also as a source

of marine biodiversity. Some marine biologists point

to evidence that the Coral Triangle is where many

reef species originated before proliferating across the

planet’s seas.

“Concepts of the Indo-Malayan area as a cradle of

diversification or as a museum for species that originated

elsewhere are not mutually exclusive propositions,” said

Gustav Paulay, Ph.D., of the Florida Museum of Natural

History, “nor are they the only ones.”

In regions where temperatures remain warm

and nutrients are plentiful year-round,

species can become specialists, which leads

to the abundance of symbiosis that can be

observed on tropical reefs. In addition to water

temperature and nutrient availability, geography,

climate, plate tectonics, habitat variety and

oceanic current circulation also influence the

wild array and distribution of underwater life.

Text and photo by Ethan Daniels

MARINE BIOGEOGRAPHY