How and when did you become a diver?

I have always lived by the sea, and one high school I

attended was very close to a rocky coastline, where I

would regularly spend my lunch break snorkeling. One

day I watched the bubble trails recede from two scuba

divers in the water, and I thought, “I want to do that.” In

1979 on the day I turned 16 years old (then the minimum

age to learn scuba), I enrolled in a scuba course. I have

been involved with diving, for work and play, ever since.

Why did you develop the health survey tool, and

what does it do for decompression research?

In the early 1990s a diver-intensive fish-farming industry

arose in South Australia. Bluefin tuna were caught at sea

and transported to coastal pens, where they were fattened

for the sashimi market. At first the industry employed

divers with recreational training, and there were a large

number of incidents of serious decompression sickness

(DCS). I worked with Derek Craig, a diver and health

and safety inspector, to characterize the decompression

practices. I needed a standardized method for collecting

postdive health-outcome information, particularly the

symptoms of DCS, from a large number of divers in

the field. The ideal method would be having medically

trained personnel go into the field to monitor the divers.

That was not practical, so I developed and validated the

diver health survey, a one-page questionnaire used for

self-reporting health status relevant to DCS.

The incidence of DCS in recreational diving is

relatively low, and divers are surprised when it occurs

because they and their buddies previously dived

similar profiles many times without any problem.

Could you tell us about variability of decompression

outcomes and how that affects your research?

It is because of this question we are having this interview.

In 1985 I had finished my undergraduate studies in

physiology and was working as a scuba instructor. One

day two friends and I were doing a wreck dive; it was a

fairly deep air decompression dive, and afterward one of

my buddies, who had done thousands of dives previously,

developed DCS. That got me thinking, “Why him, and why

that day?” and sparked my interest in DCS.

Similar dives may actually be different enough to

have a different risk of DCS even if the depth/time

profile is the same (which is unlikely outside of research

settings). For instance, if divers work hard while at

depth or are cold during decompression, their risk of

DCS is greatly increased compared to being at rest and

warm — as much as if they had doubled their bottom

time. Even in a laboratory setting, however, where dives

are conducted in a pressurized wet pot where the dive

profile, breathing gas, water temperature and work

performed can be identical for all practical purposes,

we see variability in DCS outcome. In other words,

identical dives with the same diver can result in DCS on

some occasions and not others.

Since 2000 the Navy has conducted a number of

experiments in which an individual dives the identical

dive profile numerous times, sometimes resulting in

DCS and sometimes not. That is clear evidence that an

individual’s susceptibility to DCS changes on a day-to-day

basis. There are two important messages for divers: 1)

Dives are not completely “safe” or “unsafe” — rather they

have a higher or lower risk of DCS; and 2) having done

similar dives in the past without incident is not a reason

to discount DCS. Modern decompression science is

concerned with measuring and predicting DCS risk.

How do dive computers handle the variability of

decompression outcomes?

Dive computers and decompression tables handle the

person-to-person, day-to-day variability in susceptibility

to DCS by providing a choice of relatively conservative

decompression guidance, so that most people on most

days will be safe if they dive properly.

How should dive computers be evaluated in the

development phase?

A dive computer should implement a decompression

algorithm that has been subjected to human testing

so that the DCS risk within the no-stop limits and

decompression schedules is well characterized. The

dive computer should then undergo validation testing

to make sure it faithfully produces no-stop limits and

ALERTDIVER.COM|

51

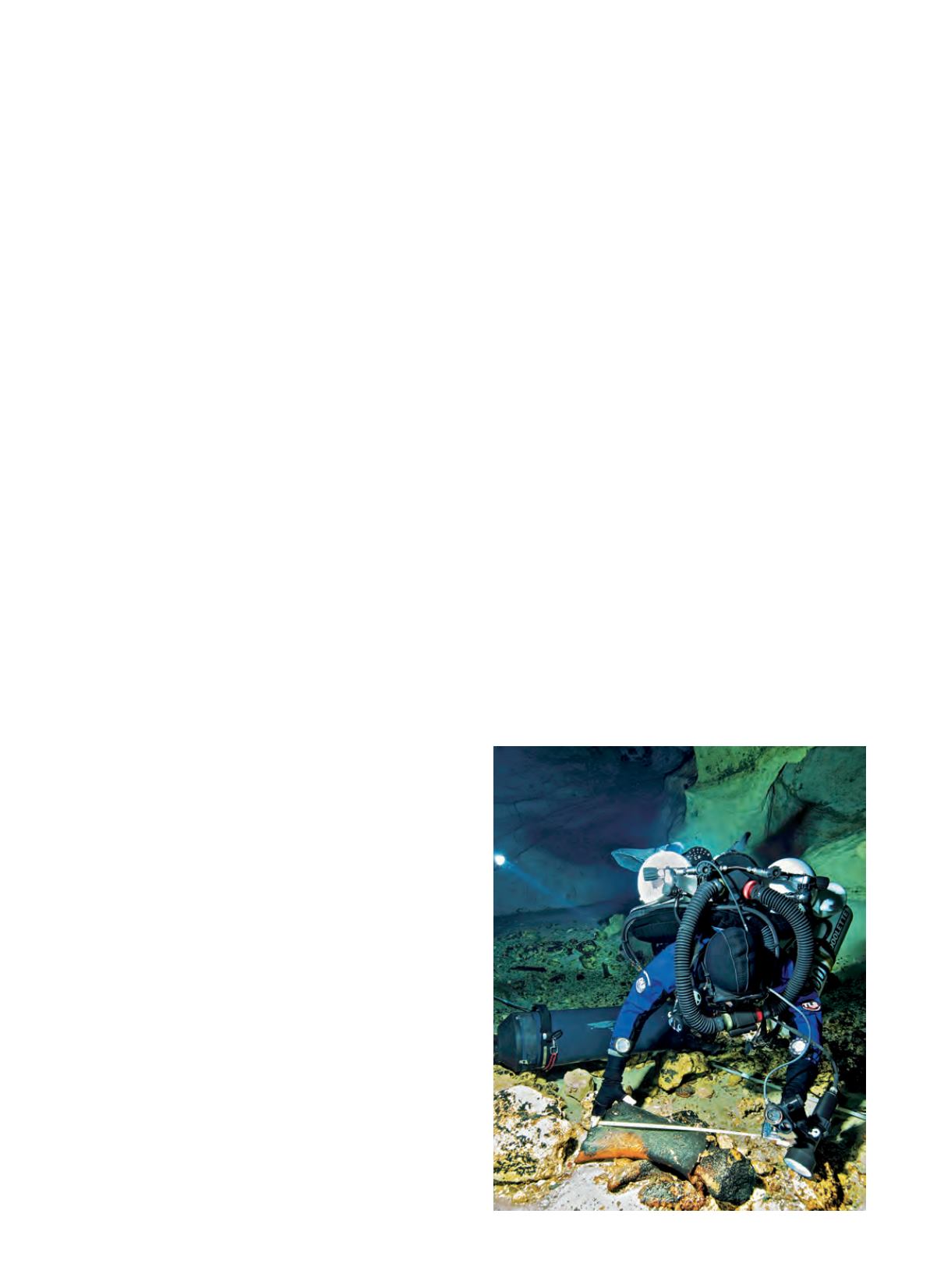

DAVID RHEA

Doolette inspects a fossil

in the Wakulla-Leon Sinks

underwater cave system.