ALERTDIVER.COM

ALERTDIVER.COM

|

47

LEADERSHIP

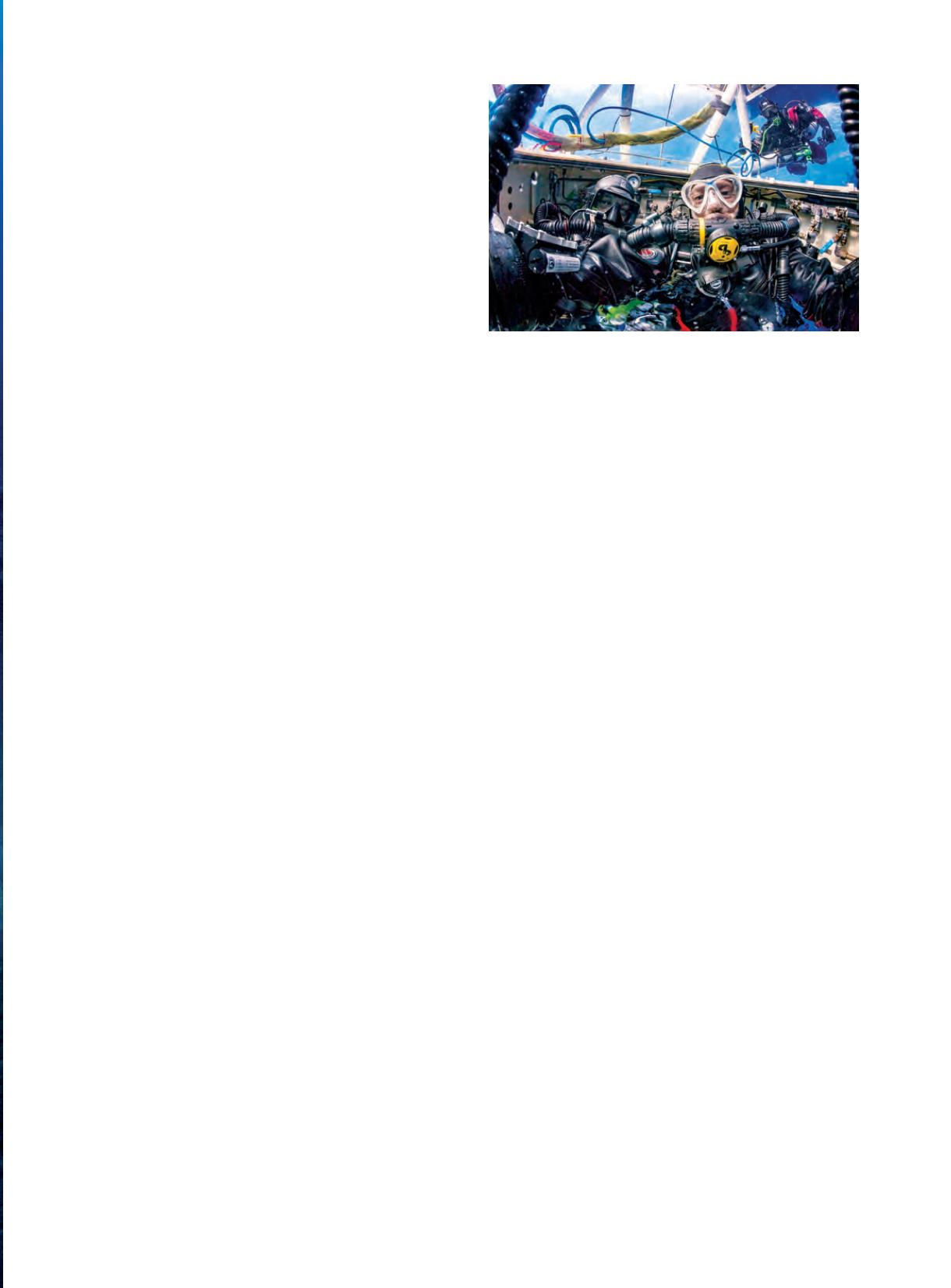

Americans Richie Kohler and Evan Kovacs, in conjunction

with a group of Russian divers, planned to take deep

wreck exploration to a new level. They had made a

single checkout dive the year before with the intention

of conducting a significant project with the Russians in

2016. Their diver support and safety plan restored my

confidence in the complicated endeavor of deep mixed-gas

rebreather diving, which had been shaken by the death of

my friend Carl Spencer on the

Britannic

in 2009.

EQUIPMENT AND OPERATIONS

A key safety feature of the dive operations was a

commercial wet diving bell. A 70-page standard

operating procedure (SOP) document outlined the

expedition’s safety protocols.

Only four divers would be in the water on dive days,

each using his own choice of rebreather with a team-

chosen diluent of 9/73 trimix. An emergency bailout

profile would be based on a carried three-gas protocol:

13/60 trimix, 20/30 trimix and 100 percent oxygen

.

All

other gas would be in the diving bell, the main point of

bailout at depth.

Diving-bell operations would be predicated by the

surface vessel maintaining a three-point mooring

position to keep the bell on station. In the case of a lost

mooring or a drastic shift in weather conditions during

the 45-plus-minute bottom phase, the diving bell could

shift from its position above the wreck to beyond where

the divers could see it. Protocols for this scenario would

be supported by ROVs and submersibles that oversaw

and maintained contact with the dive team — the

submersible pilots would direct the divers to an off-

station diving bell in mid-water, out of sight of divers on

the wreck.

Because the diving bell was a critical element of

the safety protocols, the team had to become familiar

with all aspects of its operation. Each exploration diver

would have to understand oxygen partial pressure (PO

2

)

calibration and venting, verbal and light communications,

buoyancy adjustments, onboard and surface-supplied

emergency open-circuit gas, bell master responsibilities

and management of an unconscious diver.

One nominated diver would be the dedicated bell

master for the dive and communicate with both the

dive team and the topside crew. The bell master would

confirm each diver was clear to ascend and move the

bell only when the slowest profile had cleared the stop.

Any diver ascending into the open bell at depth had

to confirm the PO

2

was within the acceptable range

before going off his loop (rebreather) and breathing

in the atmosphere of the bell. At the maximum depth

of the bell (about 300 feet) the atmosphere in the

bell would be hyperoxic with a PO

2

in excess of 2.0.

Although the vent gas was air, the PO

2

in the bell could

be dropped by venting bailout gas into the bell or

having the topside crew pump down bottom gas. With

time spent in the bell, exhaled gas from a diver’s loop

would require a venting phase to prevent changes in

buoyancy. In rough seas, buoyancy adjustments could

also be used to eliminate the hard recoil of the cables if

the bell began bouncing with the ocean.

All diving operations were conducted under the

watchful eye of the topside control center via the ROV.

Should anyone actually get lost on the wreck, the

submersible pilots could simply hold up a directional sign

with one hand while eating a sandwich with the other.

EMERGENCY PROCEDURES

For the team of technical divers, using a bell was a new

approach to a mixed-gas project. Many emergency

scenarios had to be considered and factored into the

SOP, including central nervous system oxygen toxicity, air

embolism and loss of consciousness. An unconscious diver

drill was conducted topside to provide practice securing a

diver in the bell with a ratchet strap, maintaining an open

airway and performing chest compressions.

In the scenario a diver “found unconscious” at depth

was quickly placed inside the bell and strapped against

the bulkhead with his head above water. The rescue

divers cut away his equipment and secured him. The

bell master communicated the mock emergency to

the surface and followed the directions of the topside

hyperbaric doctor. As directed, the dive team took

turns maintaining an airway and performing chest

compressions. The rescue divers remained on their

loops in the bell, and the topside crew regulated the

atmosphere in the bell for the injured diver.

The plan dictated that an injured diver should ascend

with the dive team’s decompression schedule until the

topside team determined they should lift the injured diver

out of the water. A support diver would descend to the

The 2016

Britannic

expedition employed a commercial wet diving

bell for decompression and emergencies. This was only the second

noncommercial civilian expedition in history to use a diving bell.