IMAGING

SHOOTER

92

|

FALL 2016

M

aybe there was something in

the water. Douglas David Seifert

learned to swim at what is

now one of the most revered

macrophotography destinations

in the United States: the Blue

Heron Bridge in Riviera Beach,

Fla. In the early 1960s Palm

Beach County was an absolute paradise; there were very few

dive shops and hardly any tourists who were interested in

viewing the near-shore underwater world through a facemask.

But Seifert’s childhood obsession was doing just that while

growing up on Singer Island, Fla. He went deep-sea fishing

with his father every weekend and had aquariums at home for

which he collected invertebrates and tropical fish. He became

a keen observer of fish behavior at an early age.

Although Seifert failed the classroom portion of his first

scuba class at age 12 — the math involved in the dive tables

was too much for him at

the time — later in life

he overcompensated and

became a scuba instructor,

actually teaching the math

that had once confounded

him. His immersion in

the dive industry brought

him in contact with one of

the early icons of marine

conservation in South

Florida, Norine Rouse.

“Take only pictures, kill only

time, leave only bubbles”

was her mantra, and Seifert

was her protégé. He had

great admiration for her, whom he called “this funky, crazy,

fearless 60-something-year-old woman running a dive shop.”

He recalled that she was not a fan of shark baiting, but at

that time there might be 20-30 bull or lemon sharks on a

dive even without using bait. This was also a time when any

given day diving Palm Beach County would reveal 12–24

turtles, mostly loggerheads. Rouse would dive with a buffing

pad, and the turtles would recognize her at a distance and

swim right up to her to have their shells cleaned. She had a

true rapport with marine life. Her passion for the welfare of

marine life was infectious, and helped shape Seifert’s lifelong

commitment to conservation issues.

Wanderlust and an ambition to sell TV and movie scripts

in Hollywood drove Seifert west. Soon disenchanted with the

entertainment industry, he sold everything he owned to buy

an around-the-Pacific ticket, back when such things existed.

That meant he could go somewhere such as Australia, spend

a few weeks (or months) and then hop on another jet to Fiji

or wherever. His parents gave him a Nikonos camera system

as a going-away gift, though he knew very little about how

to use it. While in Sydney, he wandered into the Dive 2000

store and met underwater photographer Kevin Deacon, who

fortuitously offered lessons to the uninitiated.

“In the film days, learning underwater photography

without instruction was a very slow and unforgiving process,”

Seifert recalled. “Kevin accelerated my learning curve, as did

a book I read almost daily

for four months:

Howard

Hall’s Guide to Successful

Underwater Photography

.

Howard and I have since

become good friends, but I

doubt he’ll ever know how

meaningful that book was to

me at that time in my life.”

Deacon’s instruction proved

invaluable when Seifert

dived with great white sharks

at Dangerous Reef, South

Australia, guided by the

incomparable Rodney Fox.

At the time, fewer than 100

people in the world had ever dived with great white sharks.

Some time later, back in Florida, Seifert met Doug Perrine

(see Shooter, Fall 2013) and went with him on a trip to the

Azores. Armed with a Nikonos RS and a 20-35mm lens,

Seifert managed to get some underwater photos of sperm

whales at a time when very few such images existed. He

showed them to the publishers of

Ocean Realm

, who happily

agreed to publish them along with an article about his

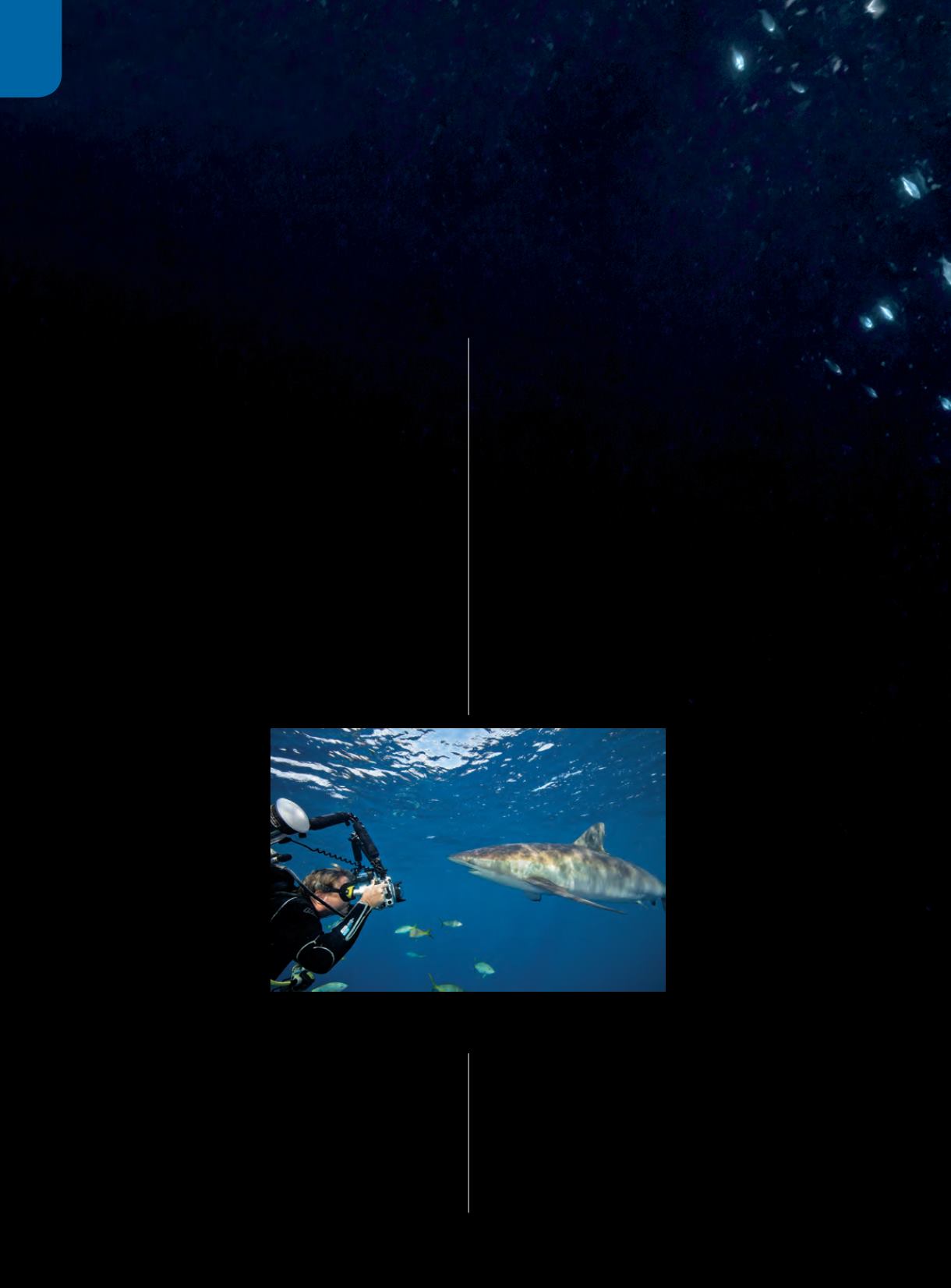

Douglas Seifert photographs a silky shark in Cuba’s

Jardines de la Reina.

THE ENDLESS SUMMER OF DOUGLAS SEIFERT

S H O O T E R

P H O T O S B Y D O U G L A S S E I F E R T ; I N T R O D U C T I O N B Y S T E P H E N F R I N K

STEPHEN FRINK