48

|

SPRING 2014

and avoid accidents. Diving officers, like other safety

professionals, are in the position that if they do their jobs

well, they help ensure that nothing, or rather nothing

untoward, happens. All the critical assessment, planning,

training, monitoring and anticipation establishes an

umbrella of protection. A good diving program will have

a culture of thoughtfulness, low stress and safe operations

with great institutional support. Each of these aspects is

necessary for a program to flourish over time.

EVALUATION

The evaluation of scientific diver competency can be an

interesting challenge. Working scientists are busy, often

disliking mandates to disrupt their activities for pool or

classroom sessions. More importantly, such sessions are

unlikely to represent the normal working conditions of

the dive team. Artificial conditions are less effective at

testing divers’ true capabilities, and the diving officer

misses the opportunity to see the specifics of operations

that are impossible to assess in summary documentation

or highly constrained scenarios. The most effective

strategy of a good diving officer, and probably the most

enjoyable approach, is to join research teams in the field.

Field evaluations can be effective when offered as

a convenience to the dive team. One method is for

the diving officer to volunteer to assist with normal

operations on the day for the small price of having the

team participate in skill evaluations at the end.

2

The

diving officer assists with regular activities to keep the day

productive while quietly evaluating normal operations of

the team. This provides insights into crew performance

and the needs of the scientific work. As an additional

benefit, the time can also refresh some skills that the

diving officer does not use on a daily basis, a useful

element since the one providing oversight can sometimes

be independent of the same protection. Running drills

and emergency simulations at the end of the working day

provides a better sense of performance with a normal

degree of fatigue. Less-than-stellar performance under

realistic conditions is more likely to capture the attention

of a diver or dive team — it is more difficult to ignore

problems evident in a normal day than a simulated one.

The completion of field evaluation days is often

extremely satisfying. The cost, particularly for diving

officers working in environmental health and safety offices

with staff from multiple disciplines, is that it is hard for

colleagues to resist a niggling (or greater) sense that these

are boondoggle days. The best way to combat that is

to have at least one other safety officer with some dive

training to participate in one of the field evaluations. My

favorite day of this type was when a fit — but minimally

experienced with diving — safety officer who had agreed

to be cross-trained declared in a staff meeting that the

“boondoggle” day constituted the hardest work he had

experienced in his career as a safety officer. It would, of

course, have become much easier as he gained experience,

but when part of the office time you have to justify is in

the ocean it is sometimes best to promote a few illusions.

A good way to investigate potential careers in diving

health and safety is to join an existing scientific diving

program. While this may be easiest for students at

institutions with programs, nonstudents may also be able

to join, often initially as volunteer divers. This can be the

gateway, providing experience and training and, if the fit is

good, more opportunity. Those who enjoy the challenge of

holding all of the pieces together to maintain a safe diving

program could find a very satisfying career path.

AD

REFERENCES

1. Dardeau MR, Pollock NW, McDonald CM, Lang MA. The

incidence of decompression illness in 10 years of scientific

diving. Diving Hyperb Med. 2012; 42(4): 195-200.

2. Ma AC, Pollock NW. Physical fitness of scientific divers:

standards and shortcomings. In: Pollock NW, Godfrey JM,

eds. Diving for Science 2007. Proceedings of the American

Academy of Underwater Sciences 26th Symposium. Dauphin

Isl, AL: AAUS, 2007: 33-43.

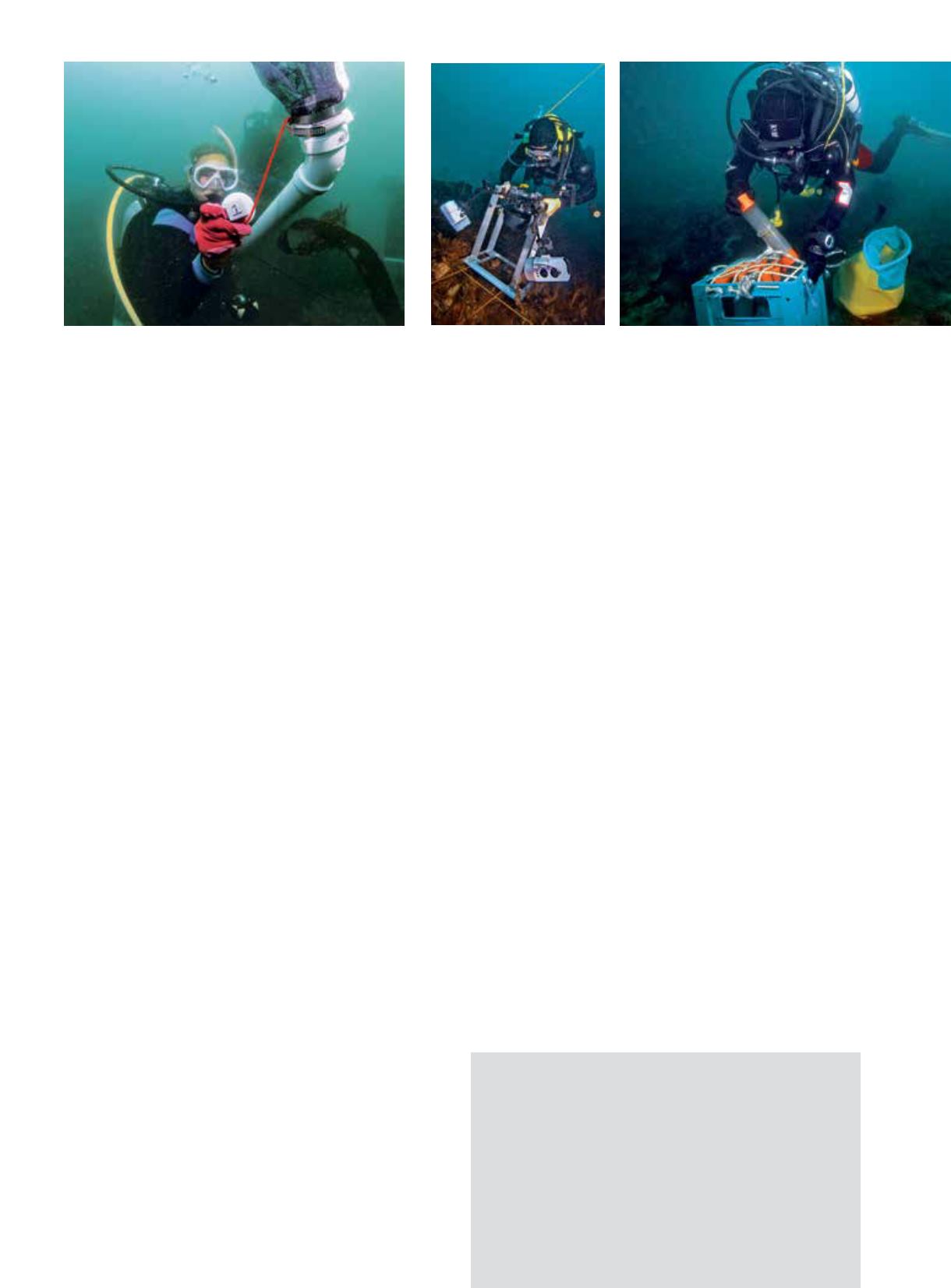

From left: A student uses a suction sampler. Standardized photoquadrat

methods are used in the quantification of ecosystem change. Hand coring

by scientific divers has been shown to give highly accurate samples for a

range of research disciplines.

The UK NERC National Facility for Scientific Diving (x2)

ERIC HEUPEL