one cause — 90 percent of lung cancer is associated

with cigarette smoking. However, only 10-15 percent of

smokers develop lung cancer in their lifetime, suggesting

that there may be a host of differences in susceptibility. A

family history of lung cancer doubles the risk of developing

lung cancer, but a specific inherited factor has not been

identified. Genetic studies of lung cancers continue,

not because we want to learn who can smoke risk-free

(smoking causes many other cancers and serious diseases)

but to find possible genetic drivers of cancer growth that

could be targeted by therapy. At present, genetic testing

may help guide the therapy in a small fraction of lung

cancer cases. The most significant target for the prevention

of lung cancer, however, is cessation of smoking, and

preventive efforts need not wait for advances in medicine

to eliminate 90 percent of lung cancer cases.

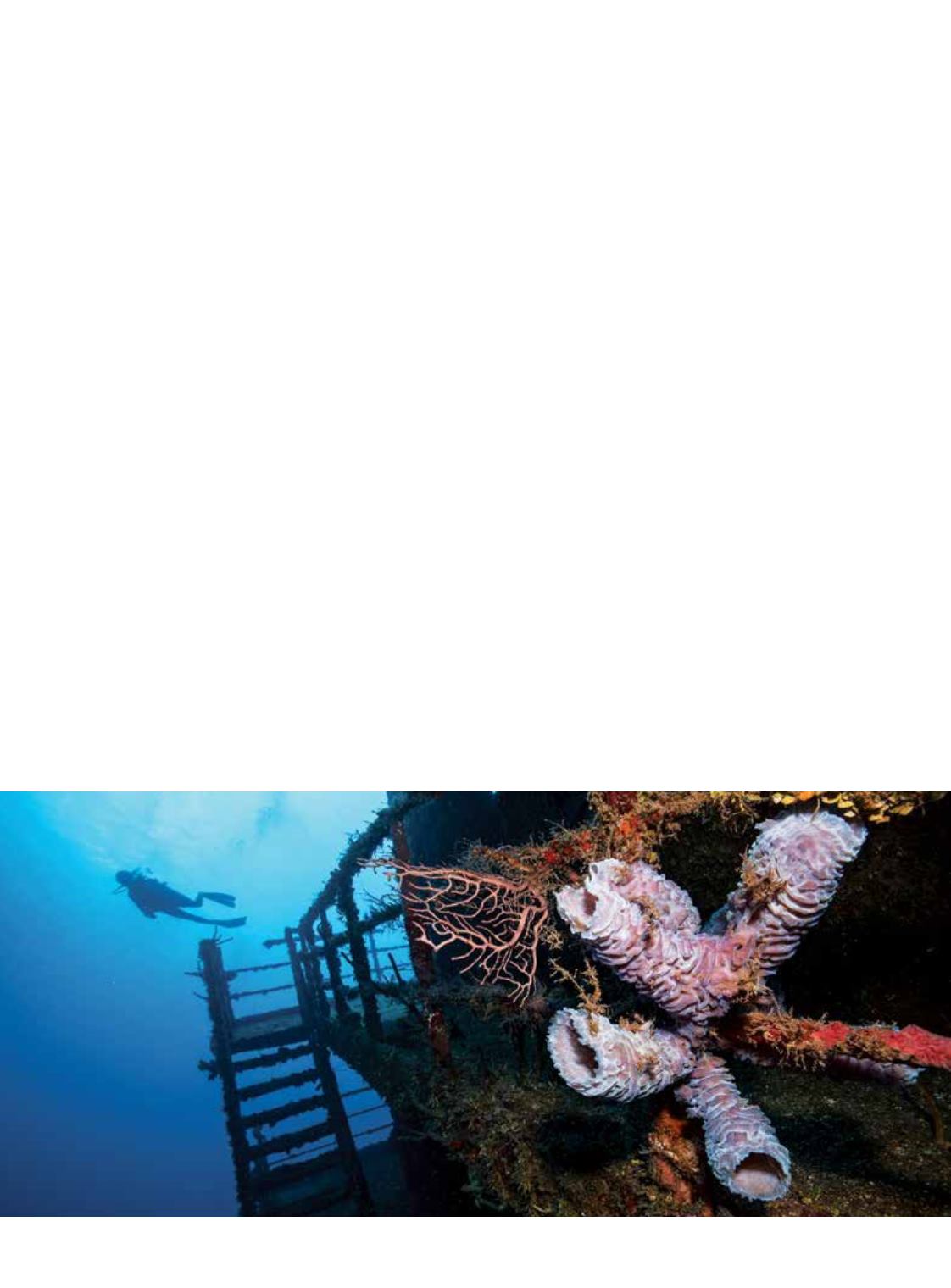

PROBLEMS WITH PRECISION IN DCS

In decompression sickness (DCS), the magnitude and

duration of exposure to pressure, the rate of decompression

and some external factors determine the outcome of a

dive. The role of tissue supersaturation with inert gas

is notorious. The deeper and longer the dive and the

faster the decompression, the greater the likelihood of

supersaturation during ascent and of venous gas emboli

(VGE), popularly called bubbles, which may result in DCS.

In severe decompression accidents the consequences are

generally grave without much variation among individuals

due to the overwhelming significance of the external

factors. However, in relatively mild dive exposures when

the pressure and pressure change are limited, occurrence of

VGE is variable but common, while occurrence of DCS is

very rare but never zero.

The variability in both of these outcomes still escapes

our comprehension. After the same dive, some divers may

develop a lot of VGE, while others will not develop bubbles

at all. In most divers who develop bubbles, the VGE are

filtered out by the lungs and cause no harm. In a fraction

of divers, however, VGE will pass through the right-to-

left shunt from the veins into the arterial circulation,

potentially blocking terminal arteries, damaging organs and

causing symptoms of DCS. Even when this arterialization

of bubbles occurs, few affected divers develop DCS.

The only constant is that with more severe dive profiles

(greater pressure, longer exposure duration and faster

decompression) the average probability of DCS increases.

Contemporary dive-computer models measure

exposure to an external factor — pressure — over time,

but they cannot measure internal factors that modify the

saturation and desaturation of the body. These include the

amount of blood that perfuses tissues per unit of time,

percent and distribution of body fat and other known

and unknown factors. Algorithms used in dive computers

take into account just the dive profile (the depth, time,

breathing gas and rate of pressure change), assume an

average body build and metabolic state, and predict the

probability of DCS. However, it is clear that the risk is not

the same for all individuals, but specific individual factors

are not known. Figure 1 shows three stages of individually

differentiated risk.

ALERTDIVER.COM|

51

STEPHEN FRINK