78

|

WINTER 2016

of deepwater animals in shallow water, the major attraction at Cenderawasih is the

congregations of whale sharks

(Rhincodon typus)

in the southern part of the reserve.

While there are a number places in the world where whale sharks congregate, such

as the Galápagos, Belize, Western Australia’s Ningaloo Reef and Donsol in the

Philippines, the sharks are resident in those places for only one to three months before

they move away. The fishermen in Cenderawasih say that the bay’s whale sharks visit

their fishing platforms throughout the year.

My exploration of this enchanting and unspoiled outpost of Indonesia began

with navigational charts, a 2010 Rapid Marine Biological Assessment report by

Mark Erdmann, Ph.D., and coordinates taken from

Diving Indonesia’s Bird’s Head

Seascape

(Jones and Shimlock, 2011). Over the vastness of the atoll I explored

layers upon layers of mighty plate corals in immaculate condition; the reef tops are

adorned with some of healthiest hard-coral meadows I have ever seen. The outside

reefs comprise dramatic vertical walls rich with sea whips and colorful sponges.

We found pockets of severely damaged reef, which might have been casualties of

dynamite fishing or coral-bleaching events. Many of these areas were in various

stages of recovery, scattered with youthful colonies of staghorn corals.

Before we came we were told to expect low fish biomass. Fish density was

indeed low at a few sites, but we repeatedly encountered massive schools along

ridges, especially where tidal or ocean currents converged. One afternoon, while

shooting a panorama of a field of hard corals, I looked up to see damselfishes

congregating for an evening spawning session. There must have been a gazillion of

them. Spellbound, I stayed until I’d nearly breathed my tank dry.

On the days we spent exploring the atoll and fringing reefs, we continued to

find healthy coral; most of the sites we documented were populated by intact

hard corals that stretched indefinitely along fringing reef slopes. Although we

spotted only two sharks, we recorded several species of reef fish, including

barracuda, eagle rays and several green and hawksbill turtles. A park ranger was

on board telling us about past sightings of dugongs and saltwater crocodiles. I was

delighted to capture images of a few endemic species: a Cenderawasih fairy wrasse,

Cenderawasih fusiliers and a new species of longnosed butterflyfish. I found the

usually deep-water Burgess’ butterflyfish in just 33 feet of water.

Burt Jones, principal photographer for Conservation International’s

Cenderawasih Bay expedition, told us to not expect colorful soft-coral foliage like

that of the Maldives or Raja Ampat, but one afternoon while in search of a site for

a night dive near the Napen Peninsula we found a Solomon’s mine of soft corals.

It was a submerged ridge complex comprising two tiny islets and three rocky

outcrops that barely broke the surface of the sea. Underwater, the terrain was a

hodgepodge gallery of estranged artists: Works similar to Van Gogh, Monet and

Picasso were on display. We found orange, red and yellow whip corals in hefty

bushes, while bright tunicates blossomed like Chinese New Year plants. Lavish

soft-coral coverage seemed to defy gravity. It was utterly out of proportion and out

of place; the phantasmagoria was a scene straight out of a Lewis Carroll story. I

named the site Dr. Seuss Reef.

Any exploration of Cenderawasih would not be complete without at least three

days of interaction with the resident whale sharks. Only in recent years did we

become aware of whale sharks frequenting the local fishing platforms (bagans).

The fishermen told us that the sharks have been around their bagans since they

began operating in the bay some 25 years ago.

About 23 of these semimobile platforms are located around Kwatisore Bay at

the southern end of the park. At dusk fishermen lower massive nets beneath the

Whale sharks are filter feeders,

using suction to pull small fish

and krill into their mouths.

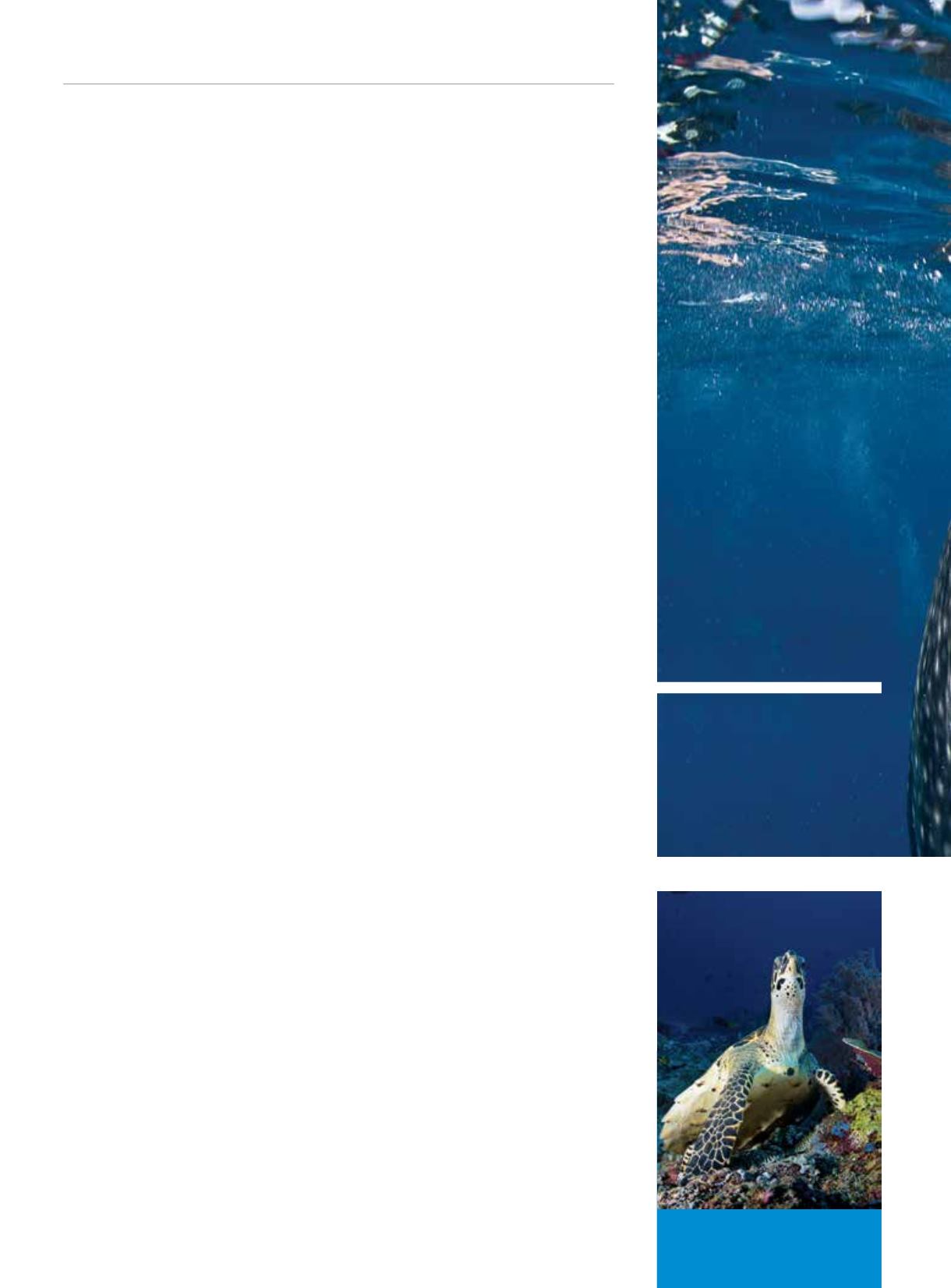

Below, from left:

A hawksbill

turtle poses for a picture. Michael

Aw holds the fin of a whale shark,

a tragic artifact of the shark-fin

trade.