ALERTDIVER.COM

ALERTDIVER.COM

|

81

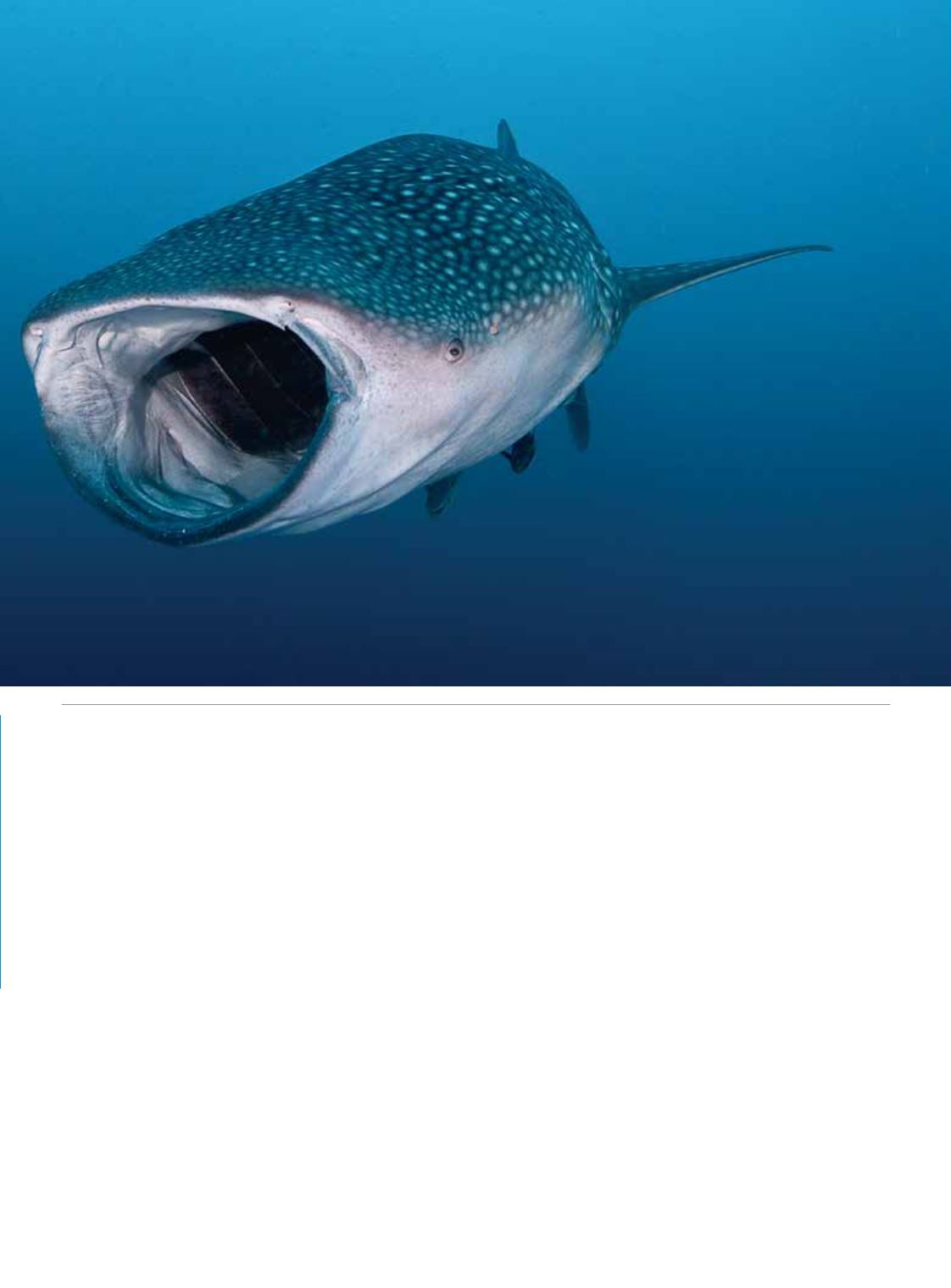

only a couple of juveniles would still be hanging around

for more handouts. At about 4 p.m. the crepuscular rays

radiating through the water acted as a dinner bell. The

sharks disregarded all table manners, frantically rushing in

with mouths agape, climbing atop one another with great

urgency, taking in as much food as possible before nightfall.

Throughout the four days we spent with these sharks,

all members of our expedition were able to approach them

closely and make eye contact on both snorkel and scuba.

They were gentle and appeared to move their powerful tails

so as to avoid hurting divers. Seemingly unopposed to our

presence, some actually rose vertically alongside us to pose

with the clumsy bubble-blowers.

At one point I was photographing three sharks as

they confronted fishermen on the bagan for more food.

Unbeknownst to me, two bigger sharks approached the

bagan from behind me. I felt a push, and in the next

moment I was like ham between bread, sandwiched

between five animals, each of which weighed around 15

tons. It was a sloppy moment, with colossal fleshy mouths

all around me, but the sharks were gentle, and I managed to

escape from among them. I was flabbergasted, and my grin

was as wide as a whale shark’s mouth.

We know that whale sharks rise to the surface to feed on

plankton and small fish, but there is much we don’t know

about them. The biggest fish in the ocean, they breathe with

gills and are ectothermic (cold-blooded), preferring to swim in

warm waters. We are unsure if the Cenderawasih population

is local, but if the shark-fin merchants were to move in, all

the animals in the bay could be harvested in just a couple of

weeks. To better understand the migratory patterns of these

sharks, Erdmann led Conservation International expeditions

to tag some of them. (Learn more at

Conservation.org .) The

tags revealed that the sharks are not permanent residents of

the bay, but some return each year.

The tagging exercise is an important effort to learn more

about these awesome animals: where and how they mate,

how they spend their early years and other mysteries. The

tags may or may not provide some answers, but the primary

concern is learning how to better protect them and their

habitat for future generations.

We termed Cenderawasih Bay a global treasure. Ocean

conservationist and diving legend Valerie Taylor has an

even better description: the eighth natural wonder of our

world. Cenderawasih is an embodiment of nature’s beauty

that fans our fervor to protect and preserve.

AD