I

t’s not unusual for those of us who live in the

Florida Keys to hear through the coconut

telegraph that someone died on a scuba dive.

You might find that surprising because most

of the reefs here are quite shallow (less than

40 feet), the water is clear and warm, and the

dive operations are experienced and professional.

There are deeper shipwrecks to dive, but in the

decades since the

Duane

and

Bibb

were sunk in 1987

(followed later by the

Vandenberg

,

Spiegel Grove

and

others) there have been few fatalities associated with the

specific hazards of shipwreck diving. But diver deaths in

the Keys persist — five in 2013, seven in 2014 and five

again in 2015.

Most likely it is no more than a numbers game. Bob

Holston, president of the Keys Association of Dive

Operators, estimates that a million divers and snorkelers

dive the reefs and wrecks of the Florida Keys each year,

all along the 110-mile island chain that runs from Key

West at the southern tip to Key Largo in the north. So

percentagewise, five to seven fatalities annually perhaps

are not unexpected and may even be quite low. Still, I

couldn’t help but wonder if there is an underlying thread

here. Why do divers die, and what might help them

survive what should be (and usually is) relatively safe and

exciting recreation?

To gain some insight, I spoke to Petar Denoble, M.D.,

D.Sc., vice president of mission at Divers Alert Network,

who said:

Heart disease is the leading cause of death for

both men and women. The most common form of

heart disease is coronary heart disease, which causes

myocardial infarction in more than 700,000 people every

year. In many cases myocardial infarction is the first

manifestation of coronary heart disease. A large number of

deaths are caused by cardiac arrest (cessation of beating)

in the absence of any known history of heart disease.

Among the risk factors for coronary heart disease, one

of the most important is lack of exercise. On the other

hand, vigorous exercise may precipitate death in people

unaccustomed to exercise of such intensity. Divers may

encounter circumstances that require bouts of vigorous

exercise, and if they are not accustomed to it, they are at

risk. Cardiac death occurs in about one-third of all scuba

diving fatalities, and the rates increase with age. For divers

to mitigate the risk of an unwanted cardiac event while

diving, the best approach is to maintain a healthy lifestyle

and exercise regularly, including bouts of vigorous exercise.

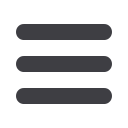

With that as background I thought about the dives

I’ve done in which circumstances required bouts of

vigorous exercise. I tend not to purposely go diving

when the winds are blowing 25 knots and the seas are

running 6-8 feet, but I have been on assignments where

deadlines trumped my better judgment, and I’ve dived

in those sorts of conditions. Recreational divers no

doubt have made similar decisions while drinking their

morning coffee in the lee of the prevailing wind, having

no concept of the conditions that might be awaiting

them a few miles offshore.

Fit To Dive?

By Stephen Frink

12

|

WINTER 2016

FROM THE SAFETY STOP

PUBLISHER’S NOTE

BOB COAKLEY

JIM BOILINI