swam off, and I boarded the boat to

exclamations of jealousy and demands

to see my images. As I scrolled through

the pictures, however, my heart sank.

Instead of the shot I had envisioned — a

defensive sea lion rimmed by strikingly

defined sunrays — the image I had taken

looked like a white ball of death rimmed

by an ugly aqua halo. Was there even a

sea lion in the middle of that blazing orb?

Instantly I knew what I had done

wrong: My camera’s exposure settings,

so perfect for the earlier images I’d taken

with the sun at my back, hadn’t been

adjusted to shoot into the sun. How

humiliating. I turned to the other divers

and shook my head sheepishly as their sympathetic

laughs echoed around me. It turned out I was in good

company; for the entire journey back to the harbor, the

other shooters on board regaled me with similar tales of

missed opportunities.

THE SUNNY SIDE OF DIGITAL IMAGING

Open any book or magazine on diving, and the chances

are excellent that you’ll find references to and photos of

the sun. Rays filtering through the water, an incredible

creature silhouetted by a sunburst, light piercing the

entrance to a cavern: All are worthy of enthusiasm, and

all have frustrated camera-toting divers. Finding and

capturing those beautiful sunrays requires patience,

effort and luck. Even if your camera settings are

appropriate, clipped highlights, banding or general loss

of detail could easily mar your photographs.

Film was better able to record contrast and subtle

color detail than most digital sensors, so a properly

exposed sunburst was more likely to yield a pleasing

result. However, most photographers have long since

transitioned to digital imaging, and we have learned

to adjust from old to new media. Digital sensors are

constantly improving, and digital cameras offer

several tools to help photographers take full

advantage of each opportunity.

Shooting images in RAW format ensures that we

retain the maximum dynamic range for each image

file. Reviewing images and histograms throughout

each dive provides constant opportunities to adjust

exposure settings, and bracketing (shooting several

slightly different exposures of the same subject)

provides a digital safety net to lessen the chances of

exposure mishaps.

SUNRAYS AND SUNBURSTS

If you have ever spent an extended safety stop mesmerized

by the effects of late-afternoon sun as it strikes shallow

water, you are familiar with shallow sunrays — also

commonly called “God’s rays” or dappled light. Water

is far denser than air, so while some of the sun’s light

energy is reflected at the water-air interface, the rays

that penetrate the water are refracted and scattered.

Depending on the time of day and surface conditions,

we can actually see defined, golden beams of light in the

water column.

Although the optical explanation seems simple, this

beautiful light effect requires a very particular set of

circumstances that aren’t encountered on every dive. First,

the deeper you go, the more light energy is diffused, so

the “beam” effect mainly occurs in shallow water. Second,

if there is a chop on the water’s surface, the sunlight will

be more scattered, which may prevent the formation of

distinct beams. Third, particulate in the water column, a

nuisance in many other imaging situations, actually help

define the sunrays. Finally, timing plays an enormous

role in capturing this effect. This phenomenon is

most likely when the sun is low in the sky; therefore

some photographers may plan early-morning or late-

afternoon dives to attempt to capture the effect.

Many of the principles for viewing and photographing

sunbursts with defined rays are the same as for shallow

sunrays. The key factors include shallow water containing

some particulate matter, calm surfaces and a low-hanging

sun. Deeper water or different times of day can present a

sunball with different visual characteristics but that’s no

less compelling of a compositional element.

|

103

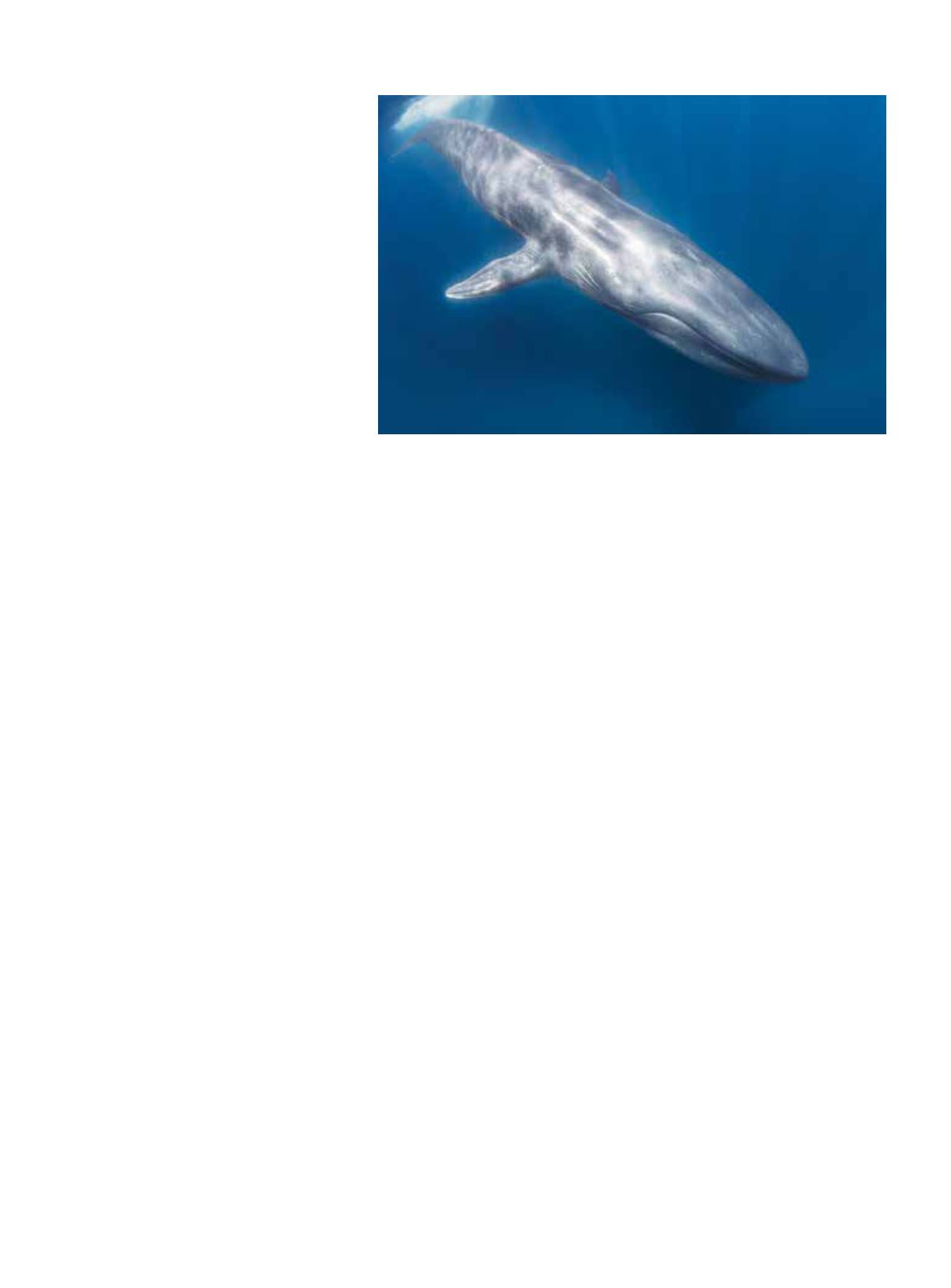

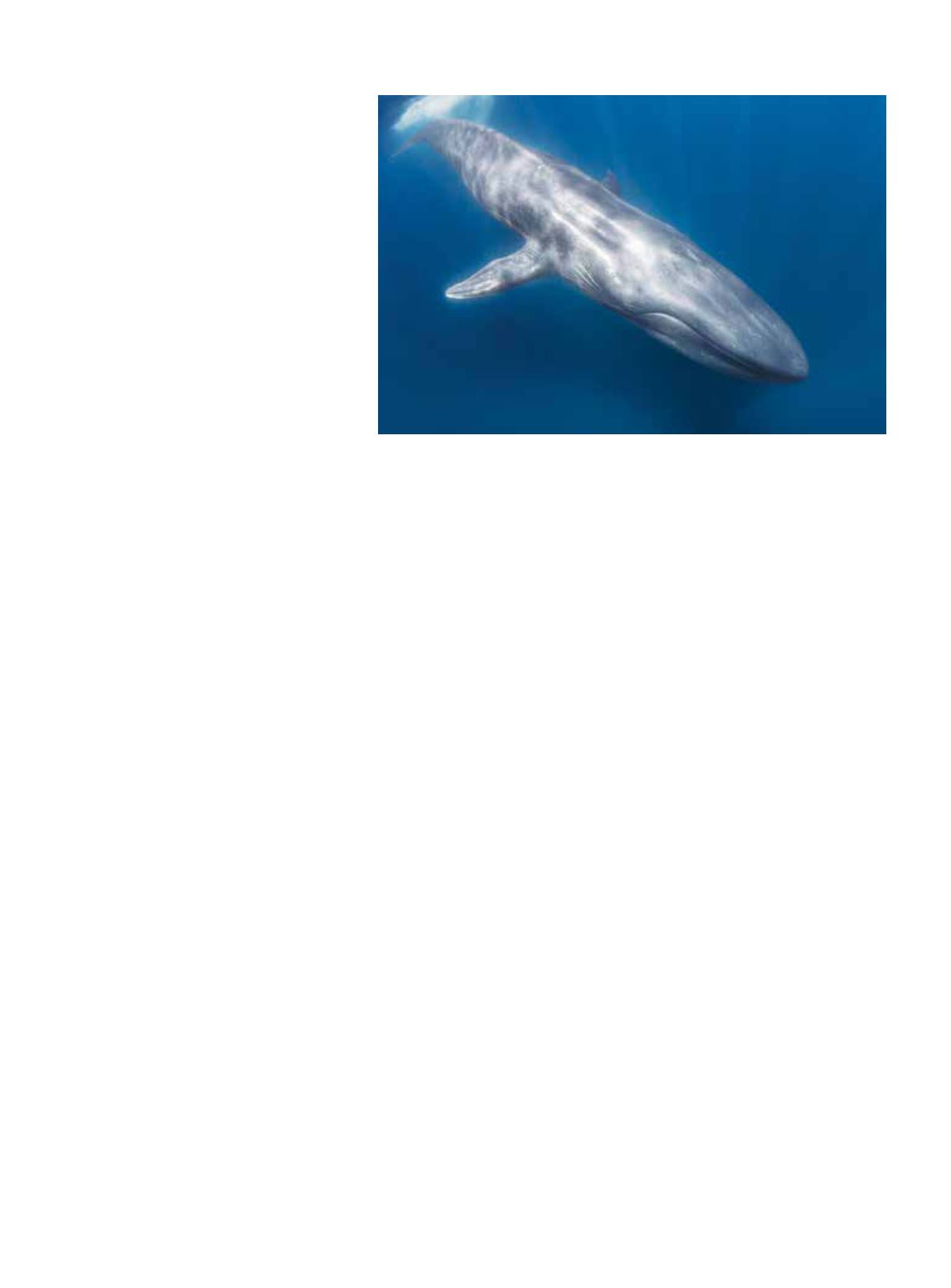

The mid-day sunrays here appear to converge at a point below the

blue whale’s head, an optical illusion that enhances the subject.