112

|

FALL 2014

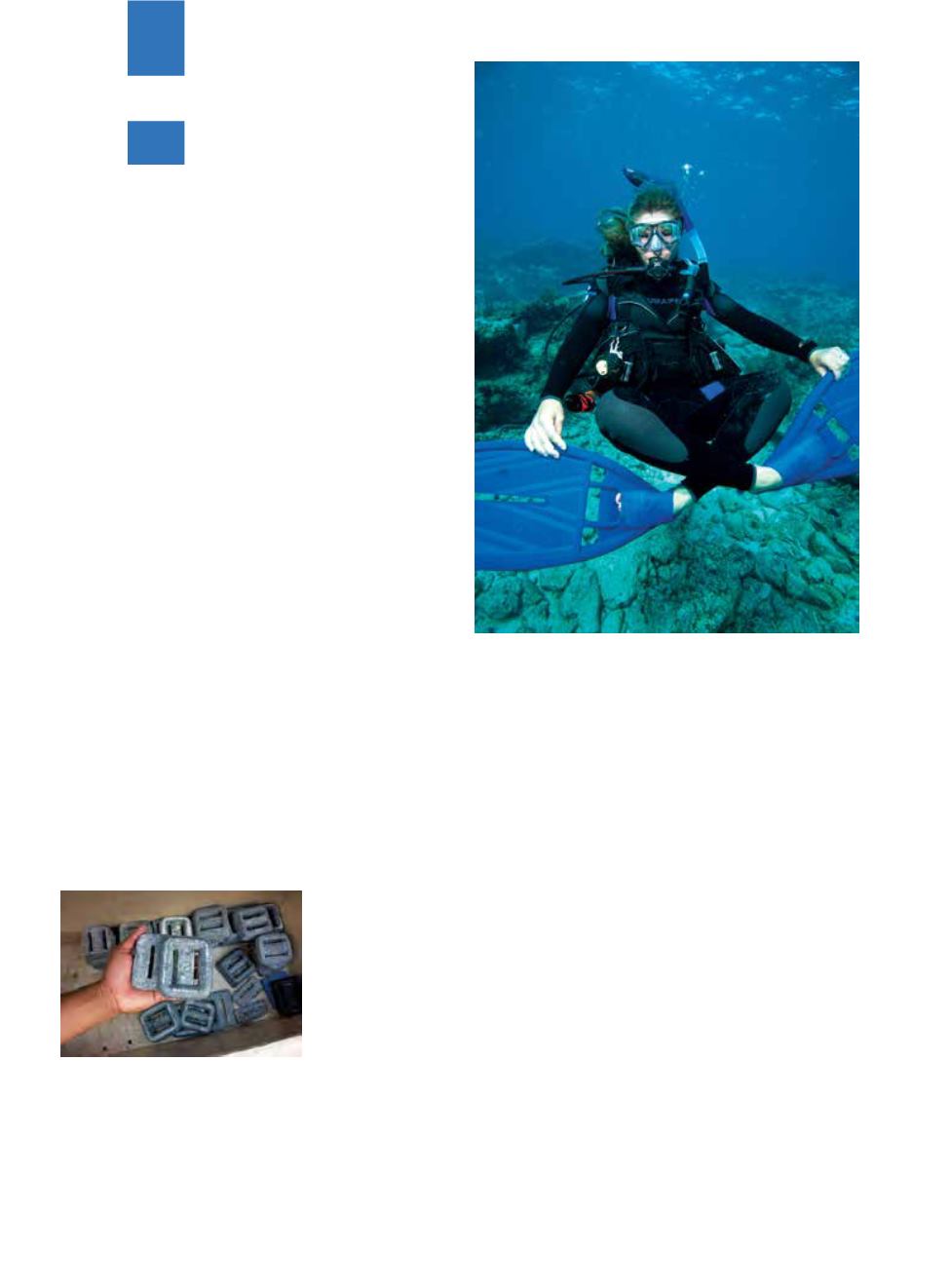

E

arly in dive training, students learn that there

are three elements involved in buoyancy

control: the buoyancy compensator (BC),

weights and lung volume. Although most

divers are familiar with the need to be properly weighted,

many do not understand all that it entails. Students and

experienced divers alike make two common errors when

it comes to weighting: diving while overweighted and

failing to adjust the amount of weight used in response to

changes in equipment and environment.

DON’T WORK TOO HARD

Improper weighting makes it harder to achieve neutral

buoyancy. Many divers who wear too much weight

do not even realize they are overweighted. The excess

weight means that to achieve neutral buoyancy the

diver has to put more air into the BC bladders, which

can create a more upright profile in the water. The

upright position increases drag when swimming,

causing the diver to expend more effort and consume

more air. Underweighted divers can also become

significantly fatigued while trying to stay down. In

addition to increasing breathing-gas consumption,

extra exertion can elevate decompression stress.

GET IT RIGHT

You may have

heard a diver

say, “This is how

much weight I

always use.” While

field testing and

prior experience

can be useful, this statement shouldn’t be the endpoint

of a dialogue about weighting. Proper weighting

requires thought and practice, and the amount of

weight worn is not fixed. Over the course of our lives,

we experience change in muscle mass, body fat and

physical fitness. Equipment, including wetsuits, wears

out and gets replaced. Dive environments differ. All

these factors affect buoyancy and require adjustments

to the amount of weight used.

To determine how much weight you need, consider

your body weight, the exposure protection you will

be wearing, the weight of your equipment and the

environment in which you will be diving. Start with

weight equivalent to 10 percent of your body weight,

which is a good baseline for a 6mm full wetsuit. For a

3mm suit, use 5 percent of your body weight. Remember

that these percentages are simply starting points.

Drysuits and thick neoprene necessitate more weight

to counter the suits’ buoyancy than do thin neoprene

or dive skins. Body composition (muscle density, for

example) will influence whether more or less weight is

needed. Diving with an aluminum tank requires more

weight than diving with a steel tank.

Saltwater is denser than freshwater, thus increasing

the buoyancy of immersed objects and requiring more

weight to descend. Dive training typically begins in

freshwater environments such as pools, quarries or

lakes, so new divers should consider that even if they

are wearing the same exposure protection they will

need to add weight for ocean diving. The exact amount

of additional weight needed will vary from person to

person. Performing a buoyancy check in each situation

will help determine the correct amount of weight to add.

B Y M A R T Y M C C A F F E R T Y , E M T - P , D M T ,

A N D P A T T Y S E E R Y , M H S , D M T

GEAR

Weight Up!

STEPHEN FRINK

STEPHEN FRINK