CATHEDRAL LIGHT

With photography, there are confusing exceptions

to the rules. Cathedral light refers to the focused

beams of sunlight that you can see within shipwrecks

and caverns or adjacent to overhanging marine or

plant life. Because this effect is viewed against dark

or shadowed backdrops, demarcated rays are visible

in relatively deeper water. Also, because these rays

are viewed when the sun penetrates the crevices of

the backdrop structure, they require a bright sun at

a specific angle. Mid-day might be the best time to

capture the effect in a kelp forest, but a cave opening

facing east might work best in the morning light.

Since the backdrop in most of these scenarios is

dark, your approach to exposure may be quite different

than for shooting sunrays during shallow reef dives. A

fast shutter speed will help to freeze the light beams,

but if it’s too fast your image won’t show the detail

of the surrounding structure. In this case, a bit of

experimentation will help fine-tune the balance between

sharp sunrays, detail and visible open-water colors.

Metering the light of the open water and adjusting your

settings accordingly can provide a good starting point.

Or you can simply bracket. A digital LCD screen will

reveal a good approximate starting point, and exposures

with apertures above and below that are good insurance

to ensure an optimal RAW image.

FOREGROUND FORETHOUGHT

When you incorporate strobe-lit foreground subjects,

shooting toward the sun can get very tricky. We’ve

mentioned that in extremely bright conditions it’s often

necessary to adjust camera settings to limit the amount

of light reaching your camera’s sensor. Increasing

shutter speed is one way to decrease background

exposure, but when you are shooting with a strobe

illuminating foreground subjects, your adjustments

are limited by the top synchronization speed of your

camera. Once you begin decreasing your ISO or

aperture size, assuming your strobe light to be constant,

you are also decreasing the exposure of your foreground

subject. When you alter either of these settings for

ambient light, you should simultaneously adjust your

strobe output accordingly, either by means of the

strobe’s power settings or the strobe-to-subject distance.

For ISO a good starting point is to double your

strobe power each time you halve your ISO; i.e., if you

are shooting at ISO 200 with your strobes at ¼ power,

then decreasing your ISO to 100 should prompt you

to increase your strobes to ½ power. No doubt, this

thought process relies upon a basic understanding

of the interrelationship between ISO, aperture and

strobe power, but your skill at this technique will

be accelerated using a trial-and-error approach that

incorporates careful review of images and histograms

throughout your dive.

Even the most powerful strobes produce a finite

amount of light that is puny compared to the sun. If

you cannot adequately light your foreground subject,

you might have to adjust your expectations more

rigorously than your camera settings. Selecting smaller

subjects, for instance, such as individual branches

of soft coral as opposed to coral-covered bommies,

will allow you to get closer, which will increase the

potential light intensity on your subject. Light-colored

or reflective subjects also require less strobe power

than dark-colored or absorptive subjects.

If all else fails, one creative trick remains: the

silhouette. By using an unlit subject to block the

sun, you can singlehandedly mitigate the limitations

of strobe synchronization speed — and potentially

inadequately exposed foregrounds. For silhouettes it’s

best to choose subjects with distinguishable shapes,

such as divers or large, iconic marine life. With

luck, the silhouette becomes a critical compositional

element, allowing you to take full advantage of the

sun’s rays.

AD

|

105

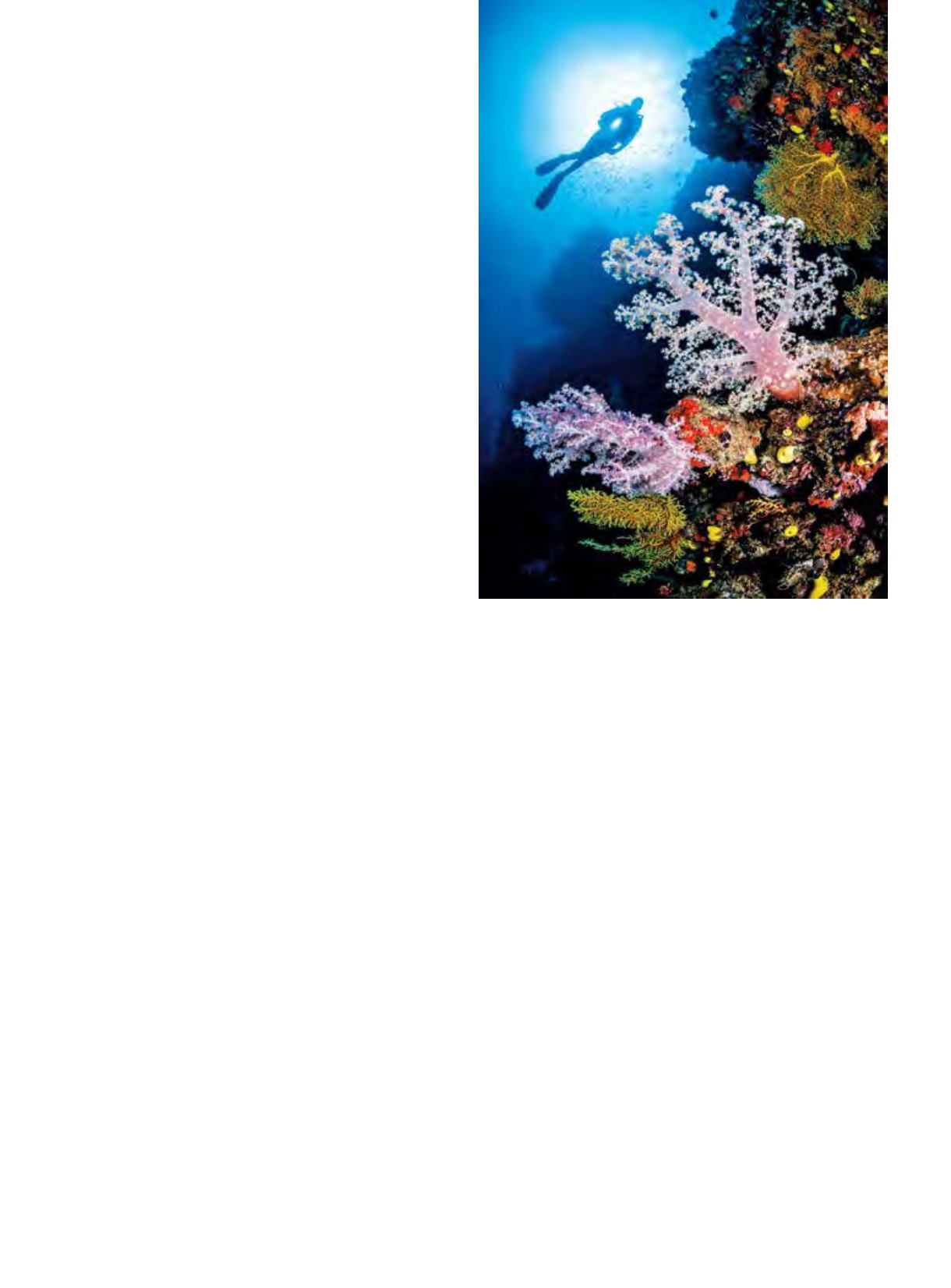

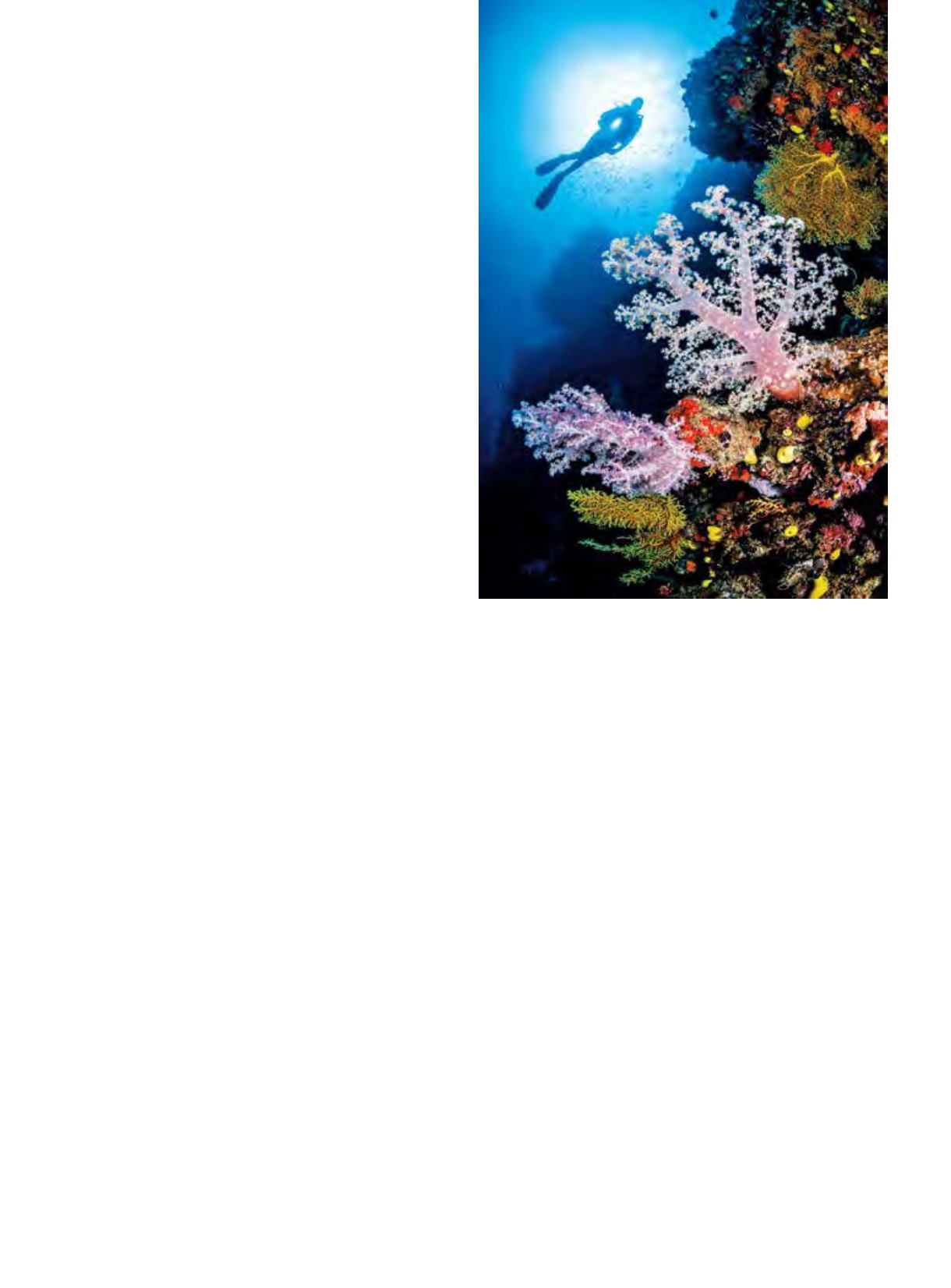

This image of a reef and diver near

Fiji was shot at 80 feet, so the sun

appears as a loosely defined ball.