|

111

1994 translocation to the MHI of 21 aggressive males

that had been biting females (sometimes fatally) at

Laysan Island. The operation successfully rebalanced

the sex ratio at Laysan and ended the assaults, but it

was a public relations disaster. Walters argues that

NOAA bringing the males to the MHI did nothing to

change the population growth because no females were

included; however, his argument often falls on deaf ears.

NOAA scientist Charles Littnan includes in his public

presentations a denial of rumors that he transports

monk seals to the MHI at night in black helicopters.

Apart from the controversy surrounding the seals’

historical habitat, the fact is that for these seals to

survive they must coexist with humans in the MHI.

Because of the greater human presence, seals in the

MHI understandably face different problems from

those in the NWHI. The beaches on which they need

to sleep and raise their young are increasingly occupied

by humans, and not all are considerate to seals. Several

animals associated with human habitation endanger

seals either directly or indirectly. For example, dogs

are known to kill seals and drive them off of beaches,

and they also have the potential to transmit canine

distemper. Cats transmit toxoplasmosis through their

feces; five seals have already died from this parasite in

the MHI. Rats transmit leptospirosis, which has been

found in seal carcasses. Additionally, seals sometimes

drown in nets, are run over by boats and get hooked,

speared, shot, clubbed and pelted with rocks.

Unlike the issues the seals face in the NWHI, most

of the problems for monk seals in the MHI are ones

that can be solved if there is a will to do so. Even if

Hawaiian residents are divided in this regard, U.S.

law mandates full protection of marine mammals and

recovery efforts for endangered species.

The Hawaiian monk seal is the most critically

endangered marine mammal under sole U.S.

jurisdiction. On some days there

are more sea lions on Pier 39

in San Francisco than there are

Hawaiian monk seals in existence.

A NOAA analysis estimates that

nearly one-third of Hawaiian

monk seals are alive only because

of interventions by its personnel. The number of

interventions is directly related to the length of the field

seasons for the NOAA team in the NWHI, and that is

determined by the recovery budget. NOAA’s monk seal

recovery plan requests $7.5 million per year to conduct

activities necessary for population recovery, but actual

funding was only $2 million to $3 million per year from

2011 to 2014. By contrast, when Alaska’s population

of Steller sea lions dropped to 25,000, the government

allocated $40 million per year for recovery efforts,

perhaps due to varying degrees of political influence.

Increasingly, monk-seal management and recovery

activities in the MHI rely on assistance from unpaid

volunteers and nonprofit organizations. After budget

and staff cuts, NOAA manager David Schofield told

volunteers: “I used to ask you to do more with less.

Now I need you to do everything with nothing.” The

Monk Seal Foundation, which was founded in 2011,

manages networks of volunteers on two islands and

supports seal protection and education activities

statewide. In 2014 the Marine Mammal Center in

Sausalito, Calif., opened Ke Kai Ola, a hospital for

monk seals, on Hawaii Island. The small facility

treats injured, diseased and malnourished seals from

throughout the MHI and NWHI and then returns the

seals to their places of origin for release.

Volunteers and nongovernmental organizations are

helping to slow the seal’s march to extinction, but the

ultimate result will not change unless both the federal

government and the citizens of Hawaii choose another

destiny for this rare and remarkable species.

“Hawaiians were always taught to keep everything

in balance. Everything in the ocean was revered,”

Ritte said. “Today in Hawaii we haven’t managed our

ocean, and now there’s not enough for everybody. The

fishermen are angry about it, and the monk seals are

smart enough to take fish from their hooks right in

front of them. That’s why

they’re angry with the seal, but the

seal was here first. As a Hawaiian,

what I’m saying is whatever

happens to the monk seal, the

same thing’s going to happen to

the Hawaiians.”

AD

FOR MORE INFORMATION

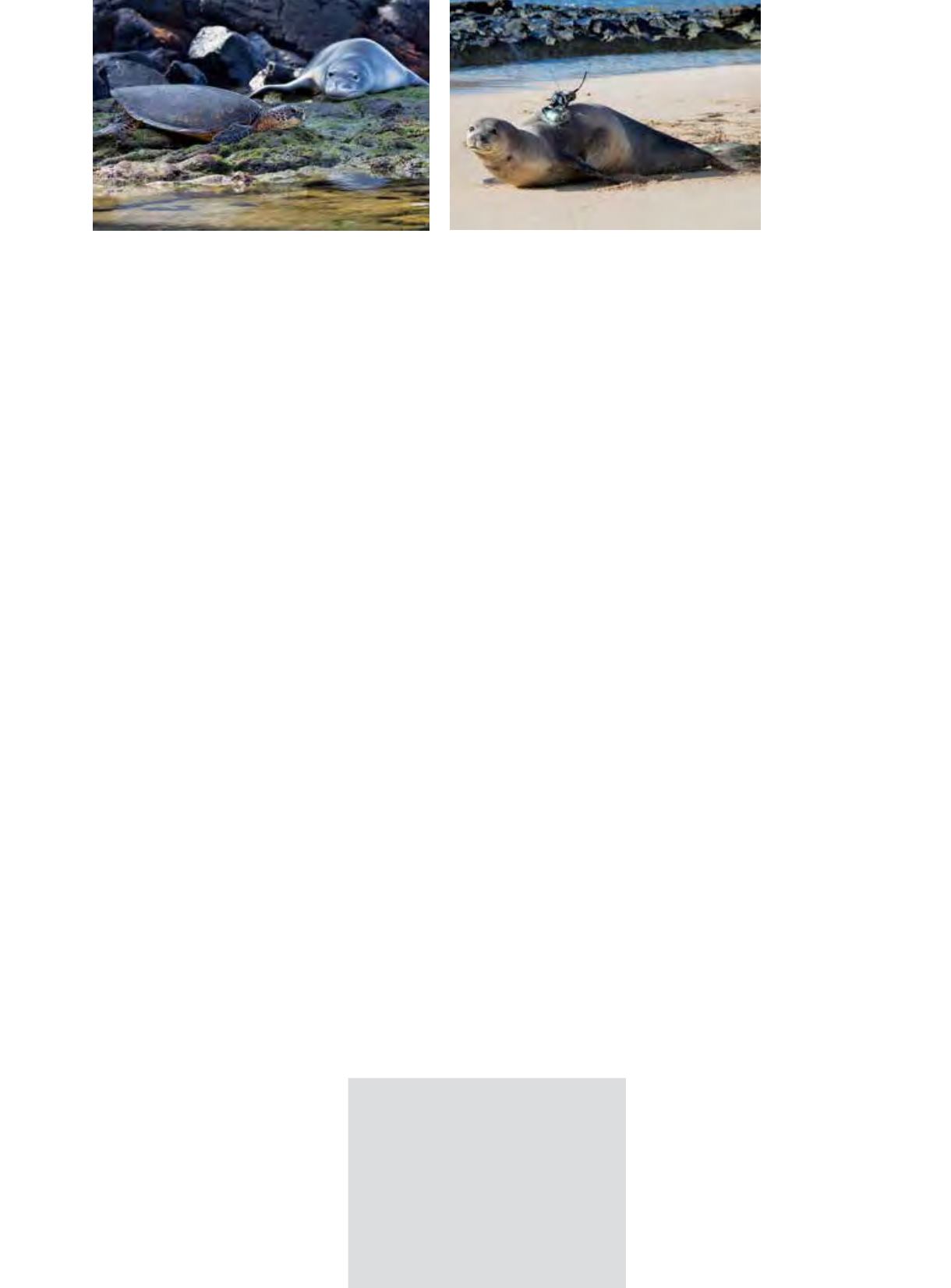

From left: A young

male shares a

resting spot with

a green sea turtle.

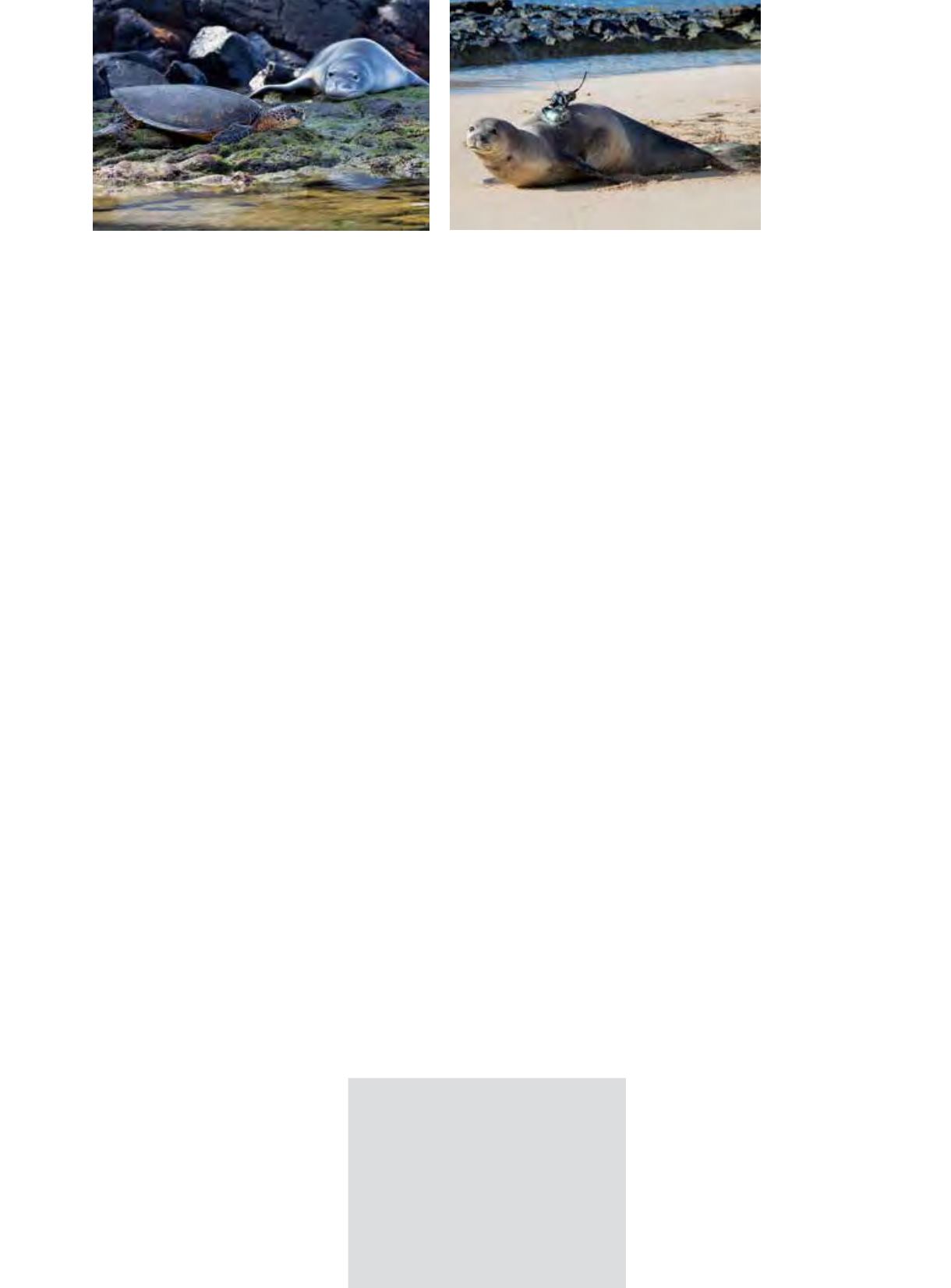

After its release by

NOAA scientists,

a seal heads back

toward the water

loaded with a

National Geographic

crittercam.