ALERTDIVER.COM

ALERTDIVER.COM

|

63

A moment later I felt a touch on my head and

turned to see a thumbs up signal. I blindly followed

Doug as he ascended — I didn’t know what was going

on. I could see he was watching his gauges. I never saw

his face until we were just about to surface. He was

slightly above me, so I had been looking at his stomach

the whole time. I don’t know why, but I never thought

about what might be happening.

At the surface he turned toward me and started

to mouth words. A pink frothy foam filled his mask

and came out of his mouth. I guess my training or

experience kicked in as I screamed at him to inflate his

BCD. He rotated away from me, and I grabbed for his

inflator button. I inflated his BCD until air flowed out

of the dump valves.

I waved my arms at the boat and screamed, “Medical

emergency!” — I didn’t want the crew to think we just

didn’t feel like diving. From there the events became a

blur punctuated by clear snippets of reality. Doug was still

facing away from me. His head bobbed with the swell.

Maybe he was just resting. I will never know why I didn’t

turn him toward me, why I didn’t look at him. Maybe

if I didn’t look then this would not be real. I handed off

Doug to the crew. They pulled and pulled, but he wasn’t

moving. I stared at the ladder.

Finally the crew began to make progress hauling up

Doug, who was still wearing all of his gear. When I saw

the integrated weights of his BCD, I remembered, “drop

the weights.” He was moving so slowly I had plenty of

time to remove each weight and place it on the deck. I

removed his fins and then my weight belt and fins. I was

so proud of myself. I placed all the gear on the deck out of

everyone’s way and didn’t lose any of the rental gear. Then

I looked up and saw the ugly truth. Doug was unconscious

and a ghastly gray color, with his head hanging to the side.

This was real; this was happening to us.

I saw a crew member getting the oxygen, and I

instinctively started pushing on Doug’s chest. I saw and

heard the oxygen tank. “

Wait, my mom uses oxygen,”

I

thought.

“There shouldn’t be a whishing sound.”

I continued

pushing on Doug’s chest. Each compression produced

more pink foam from his mouth. I wanted him to be neat

and clean, so I kept lovingly wiping the foam away.

I tried to fit my mouth over his nose and mouth.

“

Damn, why does he have such a big nose?”

I thought.

“Oh yeah, nose and mouth is child rescue breathing —

mouth-only for adults.”

I performed the rescue breaths.

I didn’t feel much or see his chest rise. I provided more

chest compressions, and more foam came forth. I

performed another rescue breath. “

How long should I

do this? What if he survives with brain damage?”

During the third cycle I felt something different; it

must have been a breath finally going in. “

Had I been

doing it wrong?”

I thought. Then a gasping breath came

from Doug’s mouth — then another breath. He was

breathing. It was gasping, labored breathing. “

Should

I have done the CPR? Was it too long?”

Later I learned

drowning victims can have reflex laryngeal spasms,

which can block rescue breaths.

The crew didn’t know what to do; they had set up the

oxygen cylinder incorrectly, and all the oxygen leaked

out. No one else took charge, so I did, albeit badly.

Somehow I rolled Doug onto his side, and after what

seemed like an eternity I looked up and saw we were

at a dock. The boat had pulled up at the closest dock

to the dive site, a small hotel/condo complex in south

Cozumel. “

Why wasn’t any one helping us?”

I thought. I

jumped up and screamed to the building for help.

Doug was breathing but still unconscious. He

remembers regaining consciousness as he was placed

into the ambulance (which had arrived a few minutes

after our boat docked). The saga continued with an

eventful ride to the hospital that included the ambulance

getting a flat tire, us flagging down a passing SUV,

stuffing all 6 feet 2 inches of Doug into the back of it

and then discovering the road we needed was closed

for construction. I couldn’t believe I saved his life on the

boat and he was going to die on the side of the road.

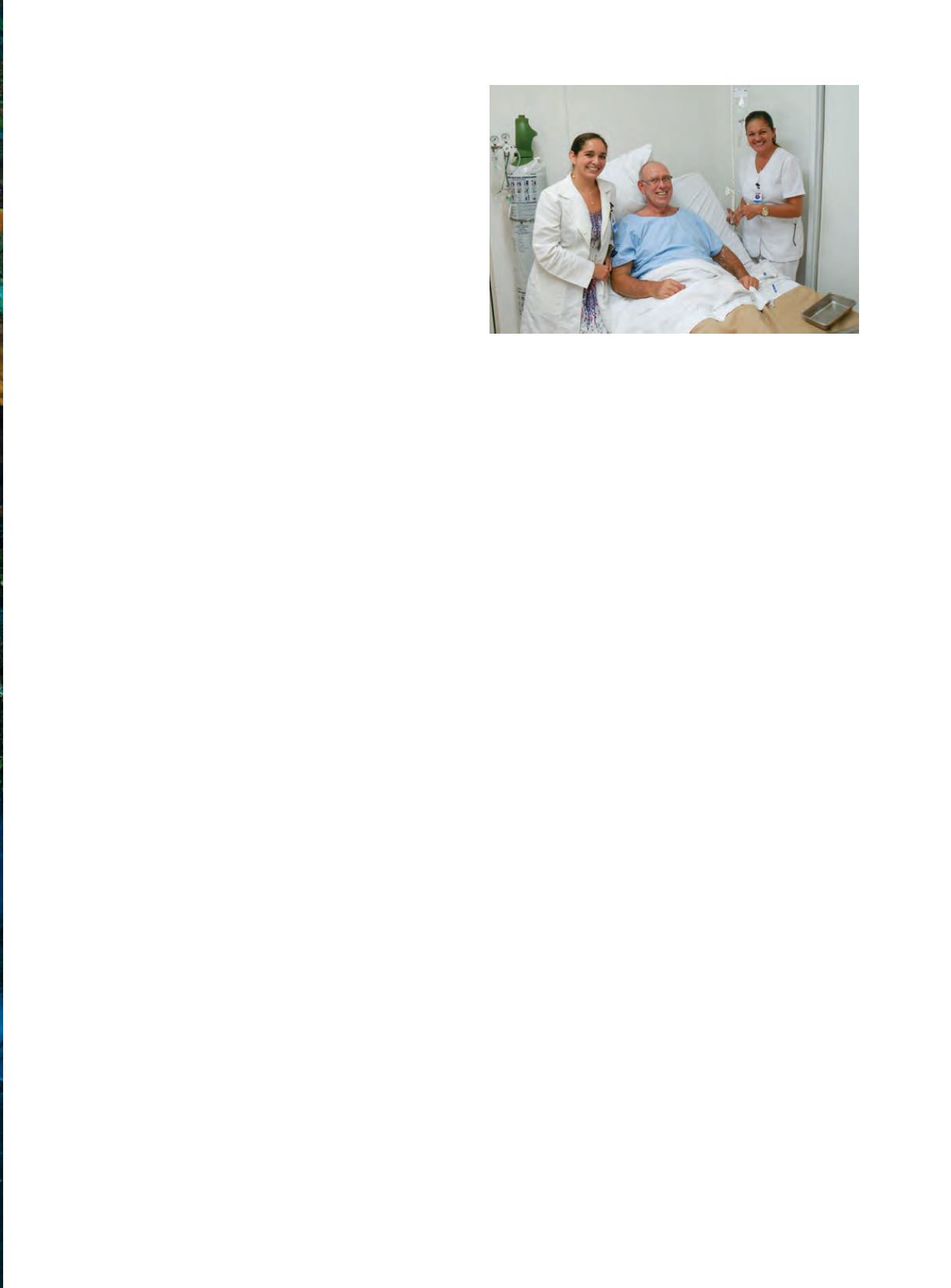

Fortunately, we made it to the hospital, where Doug

was diagnosed with pulmonary edema. After two days

in the hospital, lots of diuretics and repeated lung

X-rays, he was released.

We learned a lot from the experience: Complete

a refresher course, always stay close to your buddy,

know how to administer oxygen, stay current with

CPR training, and purchase the best DAN dive

accident insurance.

Doug is fine today, and we have completed several

dive trips since the incident. We have taken CPR

classes, and I am now certified as a rescue diver. We

are grateful every day for a second chance.

AD

Douglas Kirk recovers in the hospital after experiencing acute

pulmonary edema during a dive. His wife, Carolyn Dobbins, may

have saved his life by not only remembering her training but also

advocating for him and taking control of the situation to the best

of her ability.

CAROLYN DOBBINS