ALERTDIVER.COM

ALERTDIVER.COM

|

83

historical tropes — some that were not very accurate

and some that were accurate in many cases but not

across the board."

Seafood Watch, which is known for compiling the

latest science on farmed and wild fish and informing the

public with its trusted consumer guides,

1

has begun to

include more farmed fish in its green “best choices” and

yellow “good alternatives” listings. Bigelow says that trend

is likely to continue — mainly out of necessity.

“If we were to have all of our wild fisheries managed

at ‘best choice’ level, we still wouldn’t have enough

fish to feed us all,” Bigelow said. “There is no future

without aquaculture. So when you look at it through

that lens, it behooves us to find the most sustainable

way to farm our fish.”

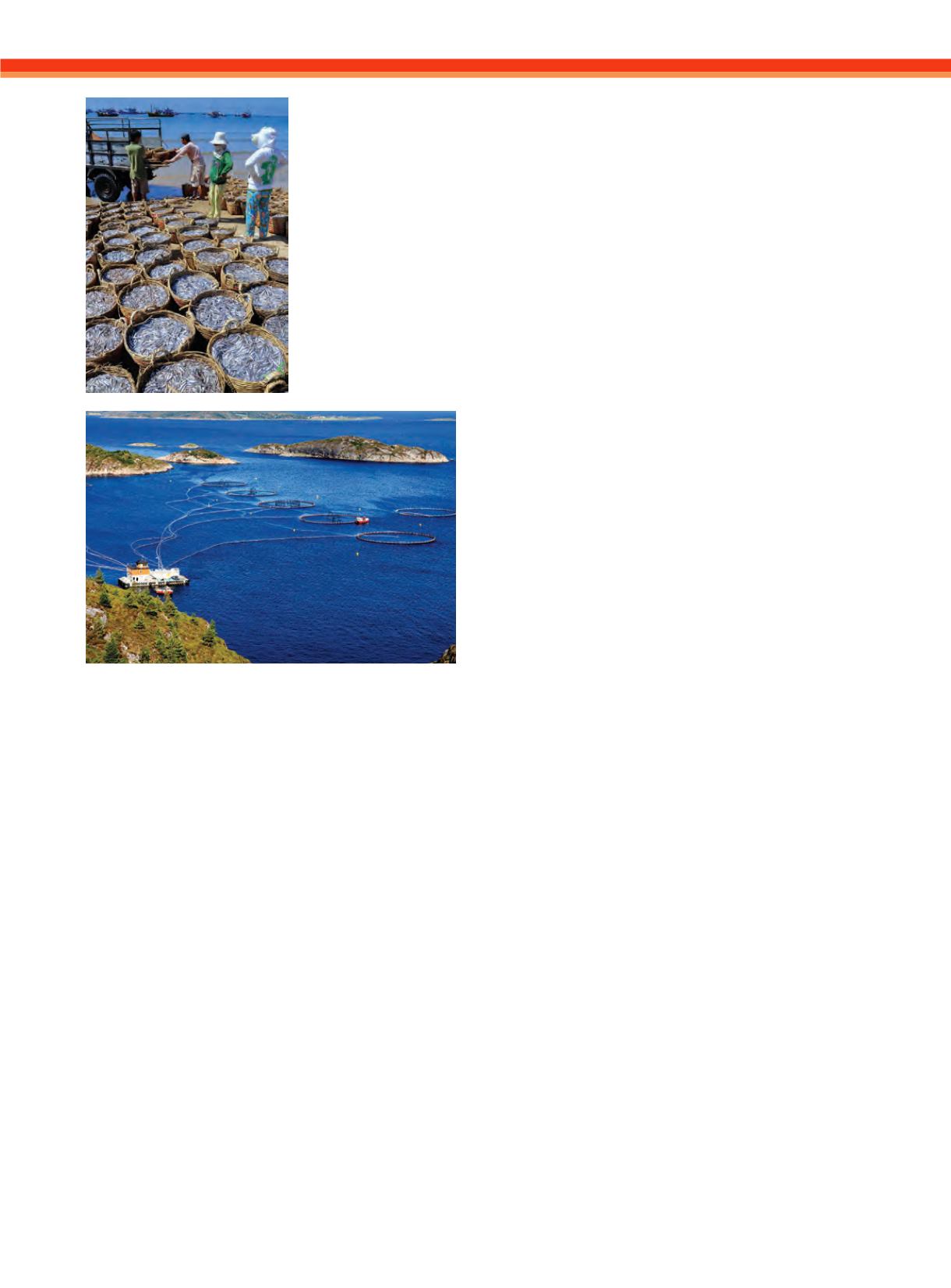

Fish farms now provide more than half of the seafood

eaten globally, and that number is rising quickly to

accommodate a growing population. It makes sense then

that, like most relatively new industries, aquaculture has

had to do a lot of growing up recently — and fast.

CHANGES IN THE AQUACULTURE INDUSTRY

For years, the biggest challenge associated with

aquaculture was the fact that farmed fish often

required sizable quantities of wild seafood to grow to

market weight. Known as the feed-conversion ratio

or “fish-in/fish-out” ratio, the quantity of wild fish

required to feed popular carnivorous species such as

salmon, tuna and shrimp was generally much higher

than the quantity of fish harvested. In the case of

salmon, it often took as much as three pounds of wild

fish to produce one pound of salmon.

Now the bulk of the industry is working to replace a

portion of that feed with high-protein plant materials

(soy meal, brewers grains, etc.), farmed insects and fish

oil. There is also a shift toward farming herbivorous

species such as tilapia, mussels and clams.

Bigelow also mentioned the trend of aquaculture

companies to move toward contained, on-land systems

and systems located in areas where escaped fish can’t

compete with their wild counterparts. Indoor fish

farms that use recirculating systems — wherein the

water is filtered and reused — are especially likely to

be sustainable. “You can drop almost any species in a

recirculating aquaculture system (RAS), and it’s going to

get a Seafood Watch green recommendation,” he said.

When companies build fish farms in the ocean,

Bigelow said, “many have stopped saying, ‘there’s wild

salmon here, so let’s just build a farm here.’” For this

reason and others, the likelihood that the fish will carry

disease or wreak biological havoc if and when they

escape into the wild is decreasing.

Taylor Voorhees, Seafood Watch senior aquaculture

scientist, agrees. He said he has seen fish farmers make

much more careful decisions about where to build

their farms in recent years.

“We’ve realized that deeper water with more tidal

flushing is typically better," Voorhees said. "And sites

that have hard bottoms are typically better than those

that have softer, muddy bottoms. All of those things are

more likely to be able to disperse the waste that comes

out of the pens and therefore have less of an impact.”

THE ARGUMENT FOR WILD

Not everyone sees aquaculture as the future of seafood.

Geoff Shester, the California program director at Oceana,

a global nonprofit aimed at protecting and restoring the

world’s oceans, would rather see more consumers opt for

wild seafood that’s low on the food chain.

Shester echoes the sentiments of Oceana’s chief

executive officer, Andy Sharpless, whose book

The

Perfect Protein

proposes a radical shift in the way

American consumers view seafood. Both Sharpless and

Shester invite seafood eaters to take an especially close

look at what’s happening to forage fish — species such

Purchasing responsibly

harvested or cultivated

seafood is not

straightforward, so

organizations such as

the Marine Stewardship

Council, Monterey Bay

Aquarium Seafood

Watch and Oceana

are working to inform

consumers and increase

transparency in the

seafood industry.

ISTOCKPHOTO.COM

ISTOCKPHOTO.COM