dive slate

//

I

f Mack and the boys stumbled out of John

Steinbeck’s Cannery Row and down the street

into the back door of Monterey Bay Aquarium,

they might mistake it for the clandestine

hatchery of an alien invasion force — think Doc

Ricketts meets exobiology lab. That seemingly

fanciful notion would not be far from the truth.

Throughout dark corridors in holding tanks bathed

in eerie pink and blue LED lights is a growing army

of hatchlings, ravenous juveniles and elusive, shape-

shifting adults that represent some of the most

otherworldly life forms on this planet.

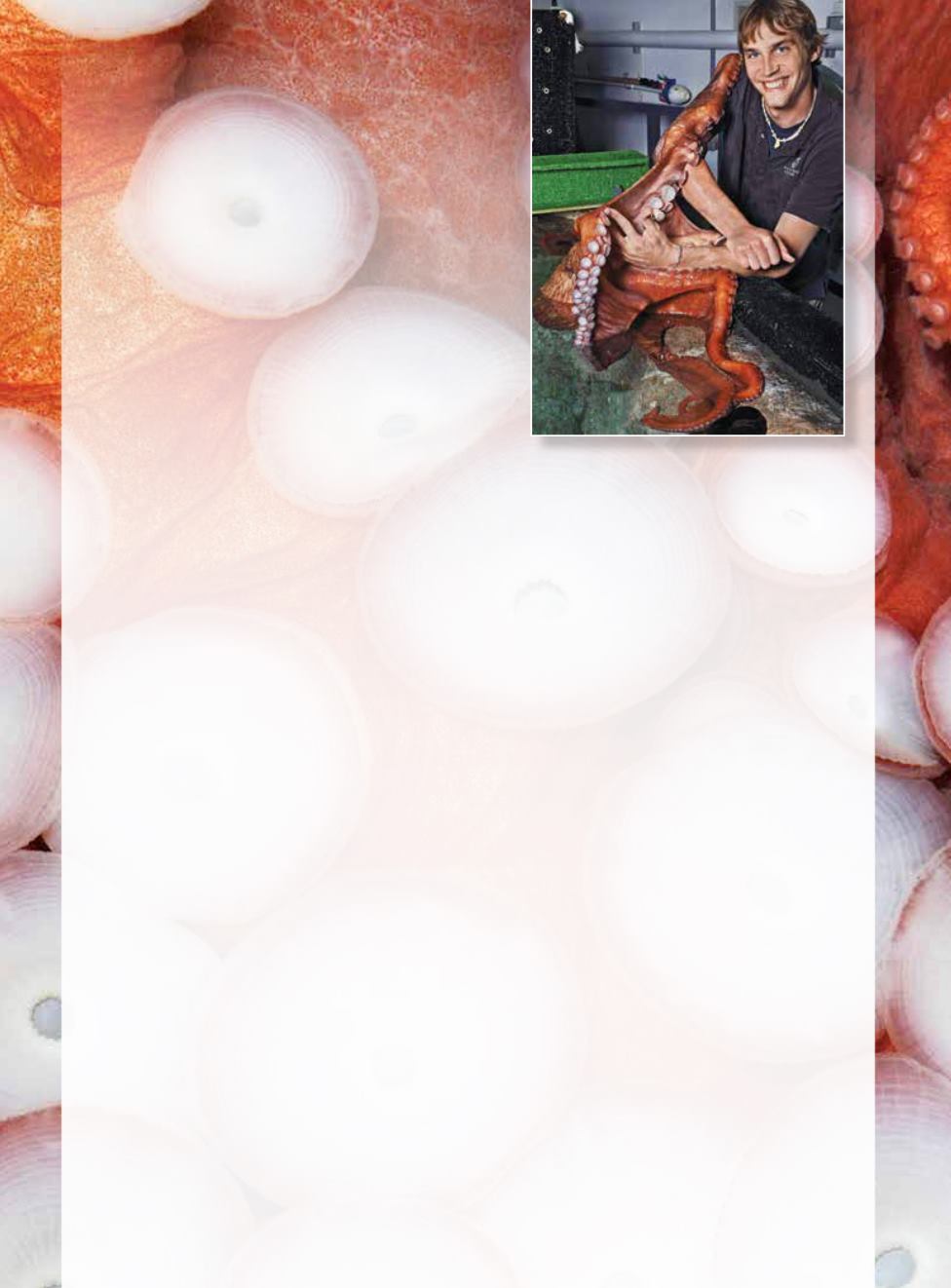

Over the past two years Paul Clarkson, the

aquarium’s curator of husbandry operations, and

his team have been engaged in a reproductive

experiment of unprecedented proportions. Their

goal: to breed and raise more than two dozen species

of cephalopods, the ancient class of mollusks that

includes octopuses, squid and cuttlefishes.

Clarkson describes the breeding program as a

monumental challenge but says it was the only way

to approach a large-scale exhibition. “These animals

for the most part live less than a year. They’re hard to

acquire, expensive and nearly impossible to transport,

and they don’t like each other,” he said, meaning that

they like each other too much — most are cannibals.

“We knew an exhibition would require us to source

animals continually, so we decided to try to bring

their full [life] cycles in house.”

“Tentacles: The Astounding Lives of Octopuses,

Squid and Cuttlefishes” features more than 30 species

of cephalopod that will rotate through a dozen

aquatic displays. The animals hail from disparate

locations ranging from the tropical Indian Ocean to

the frigid, sunless depths of Monterey Bay. Nearly 5

million visitors are expected to view the almost 4,000-

square-foot exhibition.

Among the octopuses showcased are the kaleidoscopic

wonderpus, the highly toxic flamboyant cuttlefish and

the shape-shifting mimic octopus, which can assume

the form and coloration of other marine animals. There

are bioluminescent Hawaiian bobtail squid, which bury

themselves in the sand during the day, and one of the

world’s smallest squid, the northern pygmy, which is

less than an inch long. A life-size model of a giant squid,

which can grow to the length of a greyhound bus, is

splayed overhead along the exhibit’s ceiling.

There is also a pair of giant Pacific octopuses, a

rarely seen chambered nautilus (which may have up

to 90 tentacles) and various deep-sea cephalopods,

including vampire squid collected from Monterey Bay

by the aquarium’s sister organization, the Monterey

Bay Aquarium Research Institute (MBARI). Most of

these animals have never before been exhibited.

Cephalopods were once a dominant form of life on

the planet, and some biologists believe they are poised

for a resurgence. These stealthy marine animals boast

large, intelligent brains, complex nervous systems, highly-

developed senses and the ability to instantaneously

change color, pattern and form in response to stimuli.

They play a crucial role in marine food webs as both

predators and prey in every ocean in the world from the

shallows to the abyssal depths. Humans alone consume

more than 2.2 billion pounds of cephalopods a year.

Though the number of cephalopod species (some

800 and counting) is dwarfed by the more than

30,000 species of fish, biologists suspect that their

biomass is roughly the same, and there is evidence

that biomass is increasing.

Monterey Bay Aquarium’s pioneering work comes

at a time when our knowledge of cephalopods is

undergoing a period of profound discovery. In the last

20

|

SPRING 2014

an alien invasion

“Tentacles” at Monterey Bay Aquarium

COURTESY MONTEREY BAY AQUARIUM