dive slate

//

I

had just begun to feel a little uncertain about the

spot where I was standing, so I moved back. The

grizzly bears had apparently decided to walk around

us, but they stayed very close — no more than 15 feet

away. The cubs were having trouble seeing us as they

strolled by, so they stood on their hind feet to improve

their view. My camera’s motor drive whirred away, and

one of the cubs began to climb up its mother. When it

suddenly emerged on her back, we all just melted.

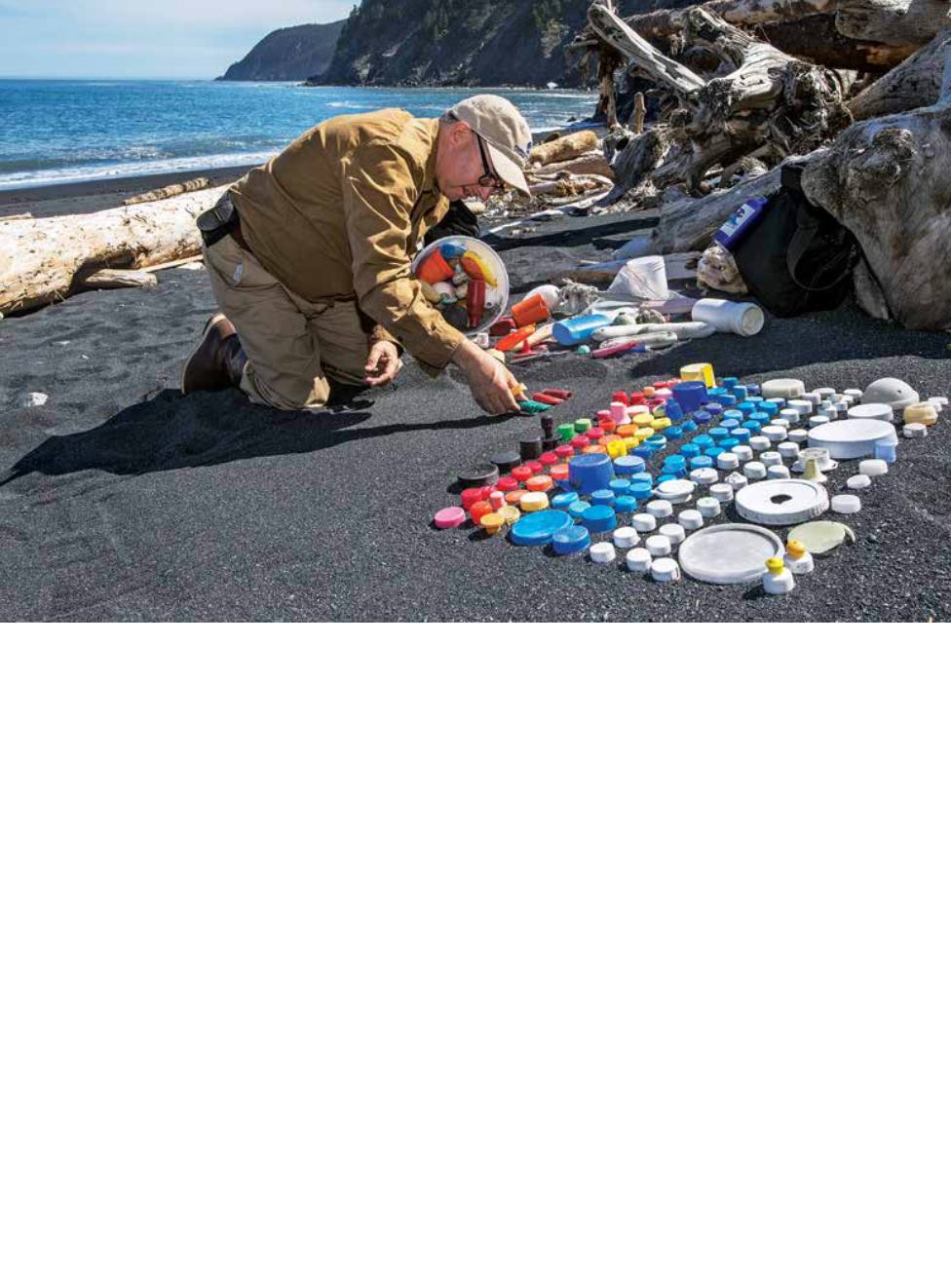

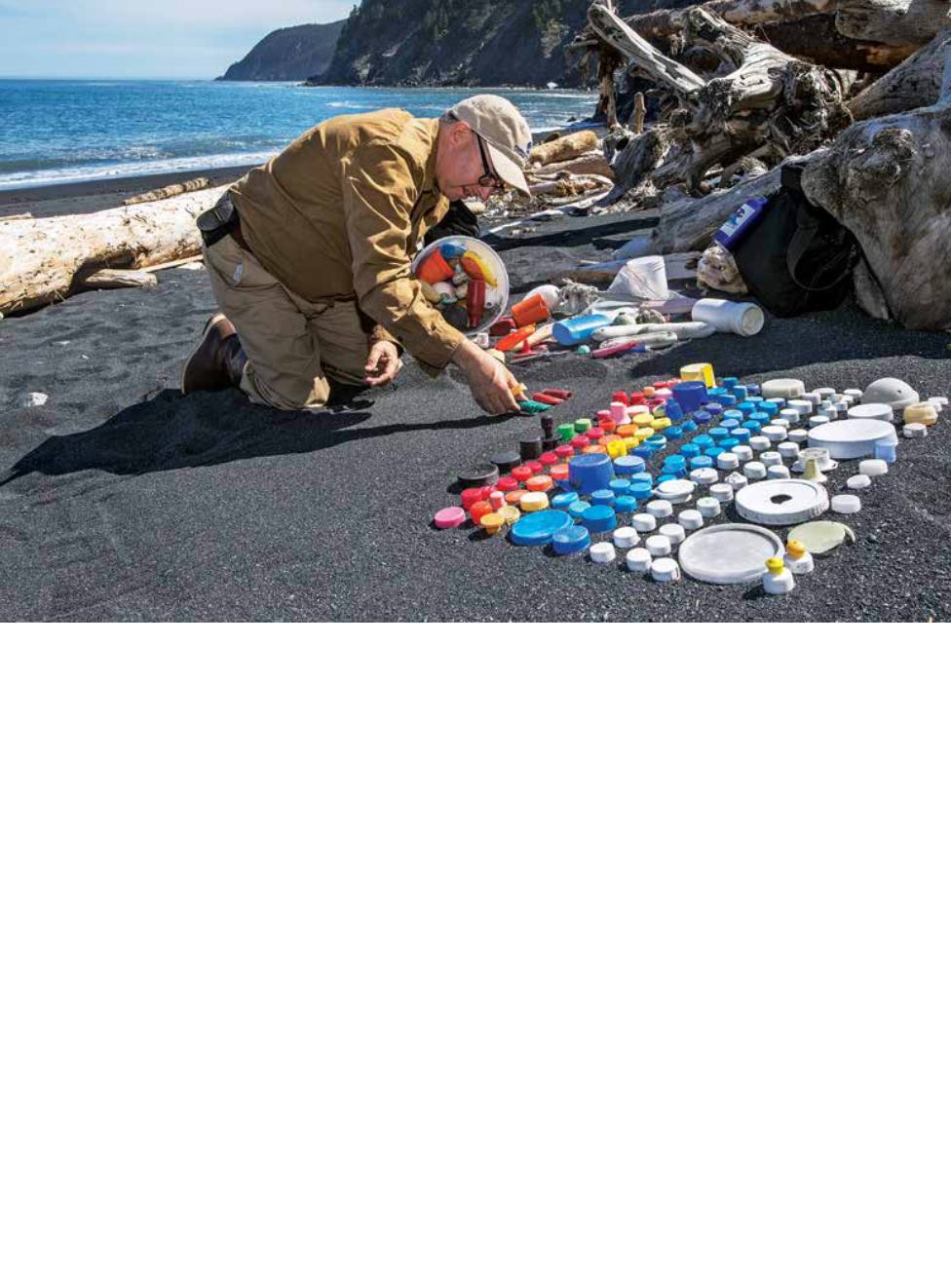

It was June 2013, and I was documenting a unique

expedition called Gyre, a weeklong cruise covering some

450 miles of Alaska’s southwest peninsula. The expedition

was sponsored by the Alaska Sea Life Center and The

Anchorage Museum, and its purpose was to highlight the

huge problem of plastic in our ocean and to help influence

human behavior through art. Other organizations involved

with the expedition included The National Oceanic and

Atmospheric Administration (NOAA), The Smithsonian

Institution, Ocean Conservancy and National Geographic.

Alaska Sea Life Center project visionary Howard

Ferren spent years planning the trip. “The ultimate

goal is to reach new audiences, influence attitudes

about consumption and waste and ultimately to change

behaviors that are fundamentally the cause of marine

debris,” Ferren said.

I was relishing the opportunity to explore this remote

territory — not only with my camera but also with an

incredible group of people. Gyre’s participants included

scientists, filmmakers, a teacher and artists, and all

shared the same mission: to highlight the striking

contrast between the rugged beauty of Alaska and the

thousands of tons of trash that are spit out of the North

Pacific Gyre onto Alaskan beaches each year.

From February through September, 2014, The

Anchorage Museum is featuring an exhibit called Gyre:

The Plastic Ocean, which presents works of art made

from garbage collected during the expedition. Artist Pam

Longobardi collected scores of fishing floats, which are

now part of her installation at the exhibit. Said Longobardi,

“Plastics are the cultural archaeology of our time. They

don’t belong in the ocean, and the tremendous, conscious

force of energy that is the ocean does everything it can to

expel this material and vomit it back onto the beach to

show us the wrong we have done.”

Most of our days were spent on isolated beaches that

can only be reached by floatplane or small boat. Some

were expansive and contained thousands of massive logs.

Others were tiny and contained no logs at all. We found

debris ranging from huge fishing nets to plastic bottles

from Japan. On one beach we found hundreds of college

football flyswatters destined for fans across the U.S.

22

|

SPRING 2014

the

g

y

r

e

project

Creating art from a plastic ocean

KIP EVANS