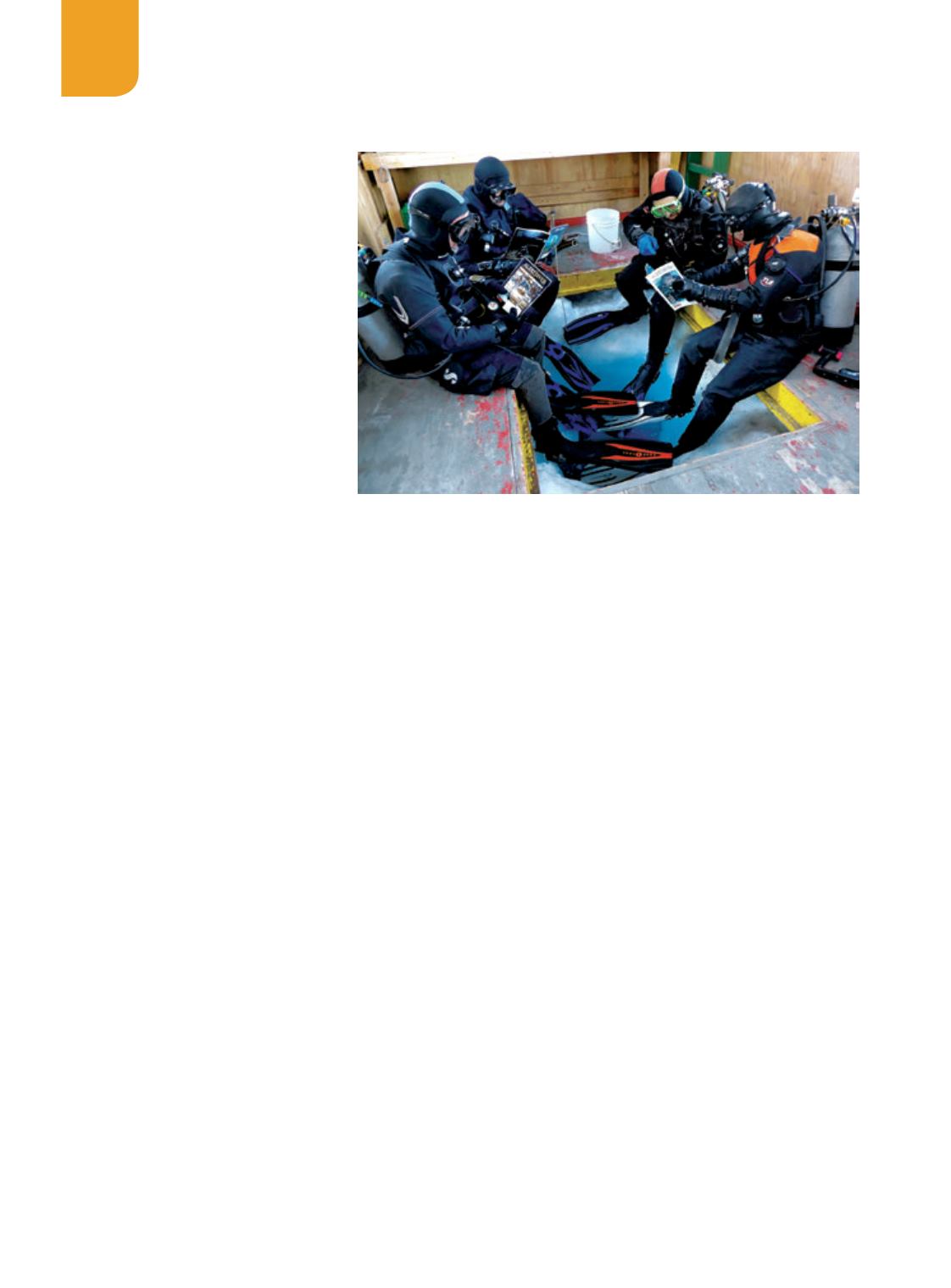

DIVE HUT DIVERSION

Our team of biologists is currently

based out of McMurdo Station,

Antarctica, studying polar

gigantism in sea spiders. The

project has us diving beneath the

sea ice at half a dozen locations

around McMurdo Sound. Sitting

in our dive huts during surface

intervals, we’ve been passing the

time by getting caught up on back

issues of

Alert Diver

.

— Tim Dwyer,

McMurdo Station, Antarctica

PERSPECTIVE DIVERSITY

Thanks for putting out another great

edition of

Alert Diver

, featuring a

really stunning portfolio by my evil

twin, Douglas Seifert, and Stephen

Frink’s thought-provoking editorial

on the public response to the tabloid

presentation of his croc photos

from Cuba (Fall 2016). Living in

our “diver’s bubble” of people with

shared experiences, it’s easy for us

to lose sight of the fact that while

the diving community has (relatively

recently) accepted the value of and

very limited threat posed by sharks,

crocs and other large marine wildlife,

this attitude is not at all shared by

the general public.

This was brought home to me

by another post that went viral

earlier this year: a drone video of

tiger sharks scavenging a whale

carcass in a very calm and orderly

fashion. Although the “action” was

so subdued that it almost looked like

it was shot in slow motion, the post

was titled “Shark Feeding Frenzy.”

Among the hundreds of comments,

I didn’t see anyone questioning

the misleading use of the term

“frenzy.” The dominant theme in the

comments was attacking the boat

captain for getting within 30 feet of

the carcass because “everyone knows

what would happen if someone were

to fall in the water” — meaning, of

course, that such a hapless person

would certainly have been instantly

devoured. Meanwhile folks like

myself who have actually been in the

water with tiger sharks feeding on

whale carcasses were laboring under

the delusion that if someone fell in,

a few startled sharks might have

dashed away briefly, then returned to

casually taking one bite at a time out

of the carcass.

We who read a lot of diving

and environmental publications

might be under the impression that

everybody knows by now that sharks

pose no menace to humans except

under rare circumstances and that

humans are a vastly greater threat

to sharks. Unfortunately, this is not

the case. Part of the problem is that

a very different story is presented by

the mainstream media, which puts

profit before truth, public welfare

and the environmental integrity of

our planet.

— Doug Perrine,

Kailua-Kona, Hawaii

I finally got around to reading your

article about diving with crocodiles

and wanted to share a few thoughts

with you.

I have long believed that with

privilege comes responsibility. I

have been privileged enough

to travel the world underwater,

and I have felt an enormous

responsibility to share that world

with others and to provide a forum

for education, particularly with

those who will probably never dive.

This brings me to your article.

I was disappointed by your very

cocky tone (“I didn’t engage with

those who commented”). You

suggested that your experiences

made you so enlightened and that

the commenters were never going to

go diving, so they couldn’t possibly

understand. I am thankful that I

never approached my students

or their opportunities to learn

from my experiences with that

same arrogant attitude. For many

years I taught students who lived only

20 miles from the coast yet had never

been to the beach. I can guarantee

you that by the time they got though

with my class they clearly understood

the long-term implications of issues

such as shark finning, ocean noise

and plastic pollution.

Perhaps you felt a bit guilty about

putting your child in the water with

crocodiles? If that is not the case, then

14

|

WINTER 2017

FROM THE SAFETY STOP

LETTERS FROM MEMBERS

COURTESY OF TIM DWYER