genetically identical to each other. To

grow more of a particular individual,

divers simply break off a small piece

from the “parent coral” and hang it

next to its siblings. Amazingly, some

of the earliest parent corals, collected

more than a decade ago as “fragments

of opportunity” broken off from the

reef by storms, are still going strong

today. “A lot of the parent fragments

have been in our nursery for 10 to 15

years now,” Ripple said. “From the

initial fragments collected, you can

create thousands and thousands of

corals. Instead of taking coral from

one reef and putting it on another, the

nursery can sustain your propagation

in perpetuity.”

SUPERCHARGING THE SCIENCE

Perhaps even more significant than the

sheer number of corals to be planted

under the latest CRF project is how

they plan to do it. “Basically, what we

did in the past was whatever corals we

had available, we would plant on the

reefs,” Ripple said. “Our goal was to

outplant as many different genotypes

as we could.” This time the approach

is different. Instead of a coral-planting

free-for-all, Ripple’s team carefully

selected a genetically diverse roster

of corals — 50 staghorn, 50 elkhorn

— based on high-resolution genome

sequencing done by Steve Vollmer,

Ph.D., at Northeastern University.

“From there, we’re planting those

genotypes across eight different reef

habitats in the same design, the same

way, in really large numbers,” she said.

By keeping meticulous records of

where each genetic strain of coral is

planted and monitoring how well they

do over time, researchers will be able

to look for links between a coral’s genes

and its ability to survive in a particular

environment. “Once we can understand

what’s actually causing them to react

differently, that has really broad

implications for further restoration

of coral reefs,” Ripple said. “So we’re

hoping that this can be an example for

other groups to follow.”

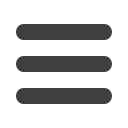

Clockwise from above:

Ken

Nedimyer tends to staghorn

coral growing on a coral tree

nursery offshore of the Florida

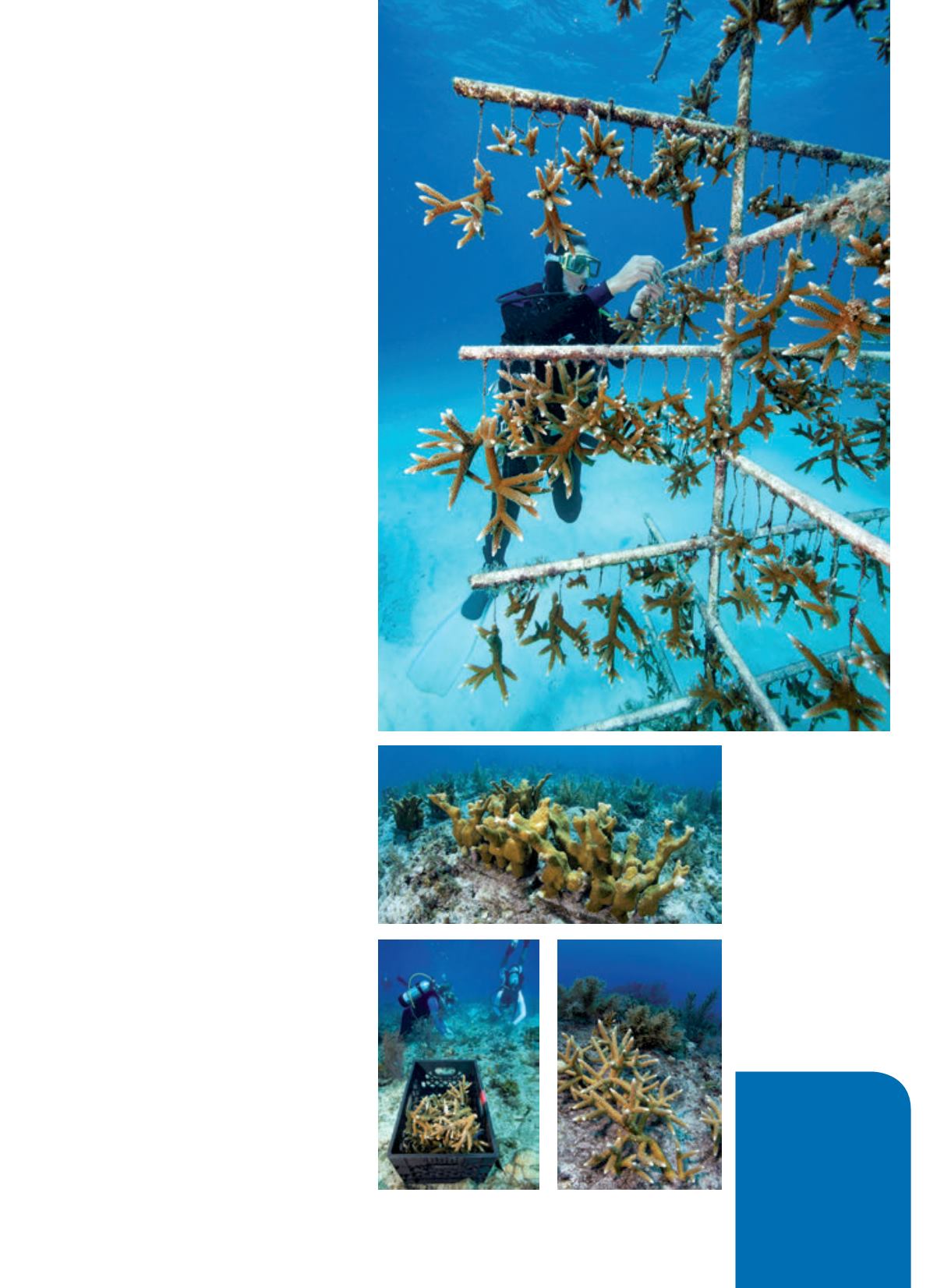

Keys. Elkhorn coral grows on

“blocks” in the CRF Snapper

Ledge Nursery to act as brood

stock for elkhorn propagation.

After three to six months,

corals grow over the epoxy

and adhere naturally to the

reef. As they continue to grow,

the corals begin to fuse into

one another, creating coral

thickets that act as habitat for

fish and invertebrates. Divers

transport crates of corals

to a restoration site, where

they will glue them to the

reef using a two-part marine

epoxy.

LEARN MORE

For more information

or to find out how you

can get involved, visit

coralrestoration.org.

ALERTDIVER.COM|

19