44

|

WINTER 2017

LIFE AQUATIC

CONCH

Chicago, Ill., have taken surveys of middens over

many years, and according to their chief scientist,

Allan Stoner, Ph.D., “[T]he conch collected by fishers

are younger than in decades past; approximately 80

percent of the conch harvested in recent years were

too young to reproduce.” Are conch numbers falling as

a result? “In the last two years, only the Jumentos Cays

had adult densities consistently above the threshold

of 100 adults per hectare [the density recommended

by the Queen Conch Expert Panel (CFRM, 2012) for a

sustainable fishery],” he said. “We found the minimum

threshold for mating to be 56 per hectare, and most of

the surveys in historically important fishing grounds

revealed densities substantially below that — from 5 or

6 per hectare to 20 or 30.

“Conch populations in the Bahamas are overfished,”

Stoner said, “and urgently need improved management.”

CONCHSERVATION

In 2013 a national campaign began in the Bahamas to

conserve conch for future generations. It was and is a

joint effort between many conservation organizations,

including the Bahamas National Trust, Bahamas Reef

Environment Educational Foundation (BREEF), the

Nature Conservancy, Community Conch, Friends of the

Environment and others. They all recognize the need to

conserve the declining population of queen conch, but

the best way to do that seems to be unclear.

Some stakeholders suggest that a closed fishing

season during spawning (April–September), similar to

that of lobster and Nassau grouper, would help. Others

say the key is to establish more marine protected areas

(MPAs) in which conch are left alone for their entire life

cycles. This seems to hold some water as conch surveys

in marine parks revealed much higher densities than

surveys outside the parks. It is likely that a combination

of both tactics, among other measures, is needed.

One thing everyone can agree on is the need for vast

improvement in enforcement of existing laws. Today,

Bahamian laws include a ban on harvesting while using

scuba (which experts say should be expanded to include

hookah — a common method for collecting conch and

lobster), a ban on collection in MPAs, a limit of six

conch per foreign vessel and export quotas.

Perhaps the most important rule states that fishers

are to take adult conch only, i.e., conch that have

had a chance to reproduce. The law may not go far

enough, however, stating only that a conch needs to

have a “well-formed lip,” which according to Lundy

“does not guarantee the conch is sexually mature — a

much better measure is lip thickness, with 15 mm

[approximately a half inch] being a good minimum.”

What can we as divers, guides and travelers do?

The most direct thing would be to abstain from eating

conch altogether, but asking about the size and age

of the conch you eat can help. Conservationists on

the ground are campaigning for everyone to “Be Sure

It’s Mature.” If conch vendors are pressured into

sourcing only full-grown conch (as the often-ignored

law requires), it would be a small victory in an area in

which victories are needed.

I suggest not limiting this standard to conch. If we

educate ourselves about the conservation issues of

the places we travel to we can make informed choices

about what we eat and who we patronize. As the

saying goes, “You vote with your wallet every day,” and

what we purchase (or don’t) does make a difference.

When I moved to the Bahamas I had no idea conch

were in trouble — or how cool they are. I no longer

look at conch and think only of food; I am amazed by

them and always happy to see them hopping along on

the seafloor.

AD

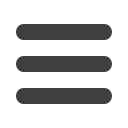

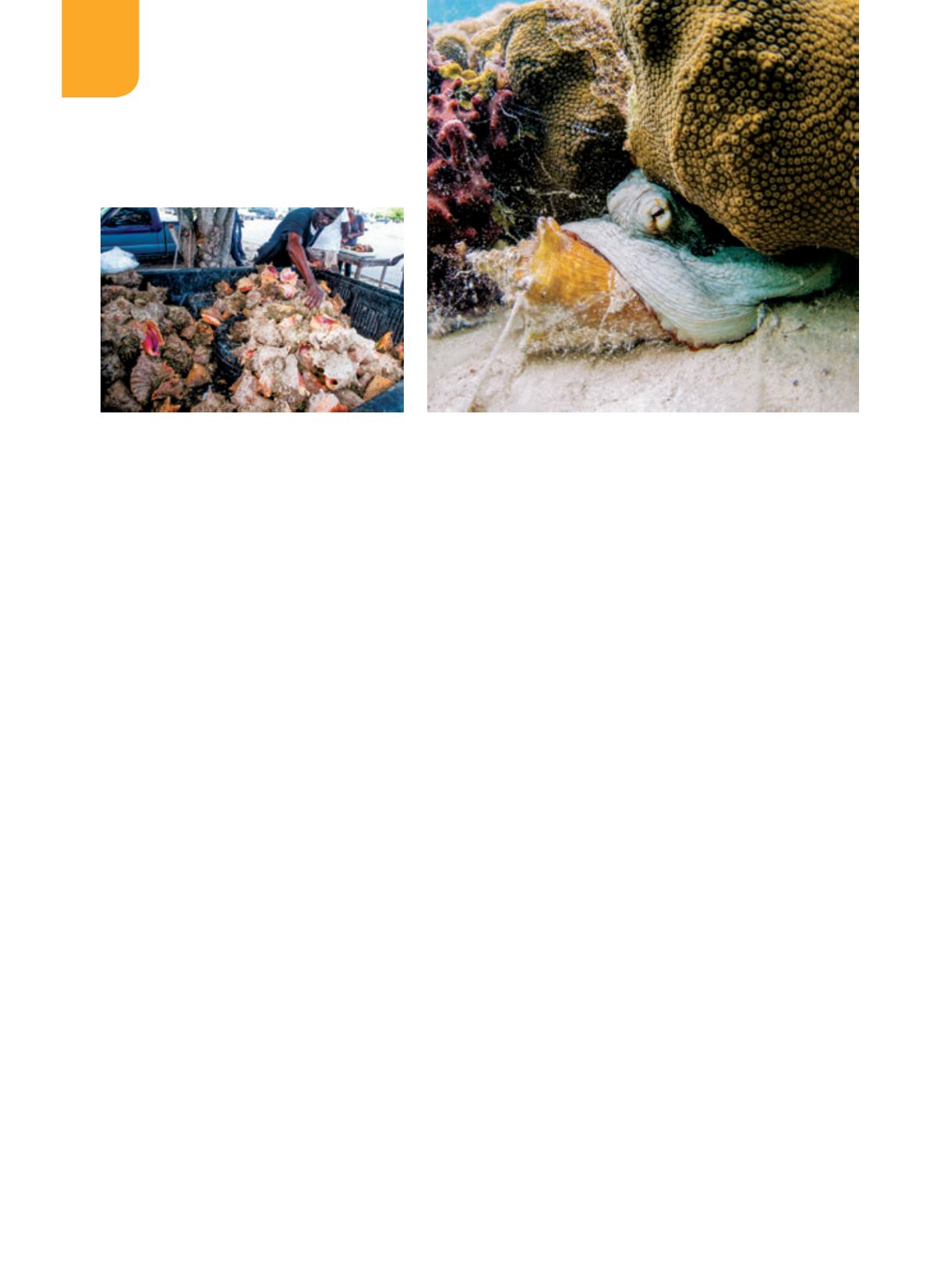

From left:

Fisherman load a pickup truck with a large

catch of conch. They will crack the animals out of

their shells at the roadside to sell to tourists and

locals. Humans aren’t the only species that enjoys

eating conch.