season), I finally got down there to dive through

the National Science Foundation. After that, I

had all the imagery I needed to play my role in

what followed.

SF:

I look at your photography and admire not

only your vision but also the environmental

adversity you must have had to overcome to

work there. Is it as hard as it looks?

JW:

Again, thank you. But the photography is

surprisingly easy, except for the effect the cold water

had on battery life — I needed lithium batteries for

my strobes. Also, remember I was working with

2006 technology. The high ISO capabilities of today’s

cameras would have been welcome, but the best at

the time was my Canon 1Ds Mark II (in a Seacam

housing with Inon Z-240 strobes). It was physically

cold, but it was so stunningly beautiful I often didn’t

notice the cold until my hands started aching and

straining against the stiff drysuit gloves. Doug Allan

of the BBC gave me a pair of his three-finger wet

mittens, which gave my hands more freedom, and

that was transformational for my work.

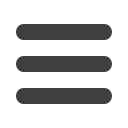

PACK ICE

The Inuit peoples of northern Alaska have 97 words to describe sea ice. We were

cutting through a painting. Sea ice forms every year as temperatures drop to

–40°F, freezing into an unbroken sheet of ice up to 10 feet thick, effectively

doubling the size of the continent. In between the freeze and the melt, this desert

of drifting ice forms the basis for one of the largest, richest and most dynamic

ecosystems on Earth.

ALERTDIVER.COM| 93

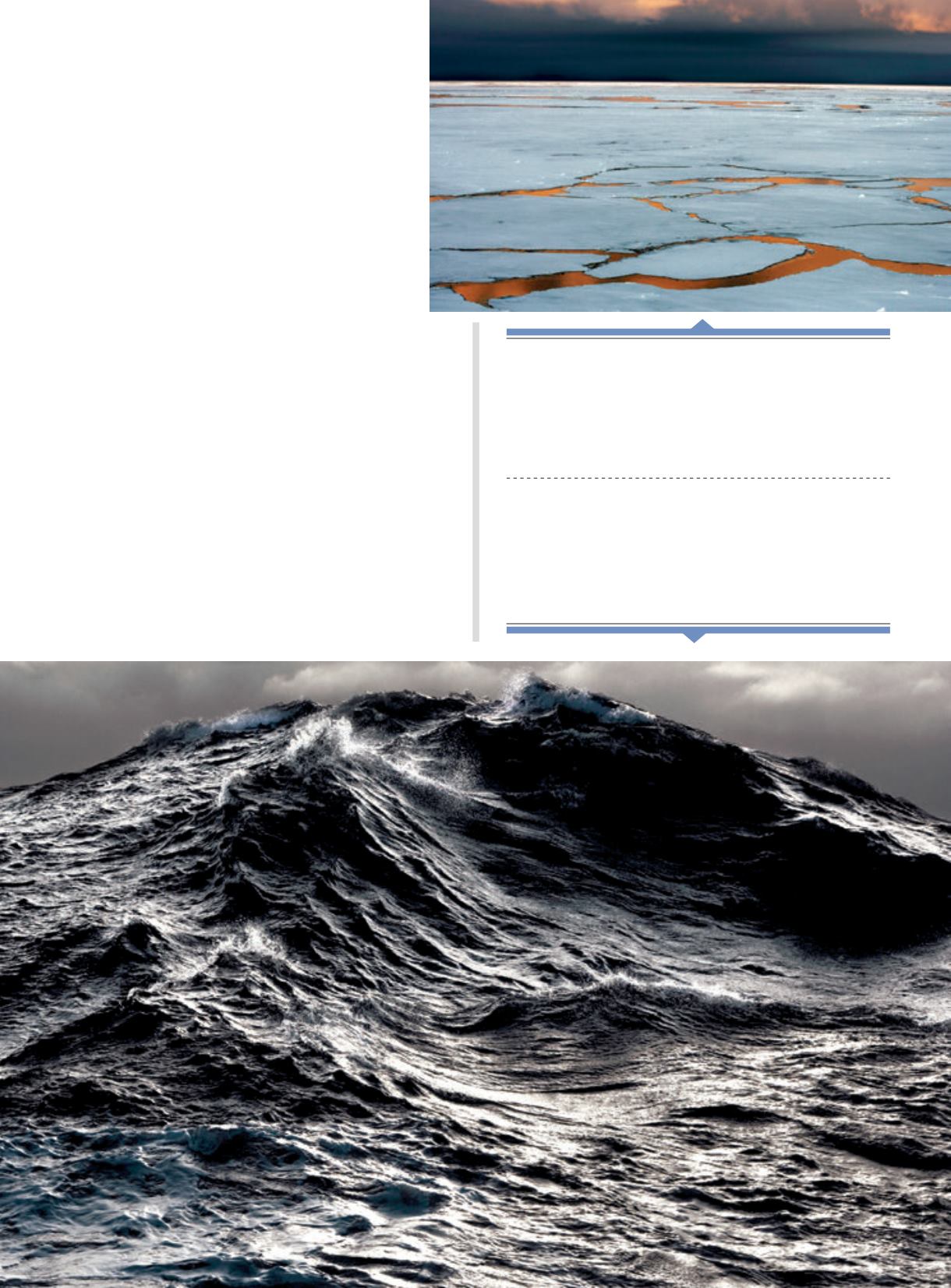

SOUTHERN OCEAN WAVE

In a pocket between towering 30-foot swells, the icebreaker rolled 35 degrees

left then right, sending an angry curtain of salt-white spray 50 feet into the air.

I lasted only 10 minutes photographing on a low deck, strapped to the handrail

with a climbing harness. It was terrifying, yet the raw power of the waves and

spray sent my heart racing as I rode the great green and yellow chariot south

from New Zealand toward the southernmost body of water in the world.