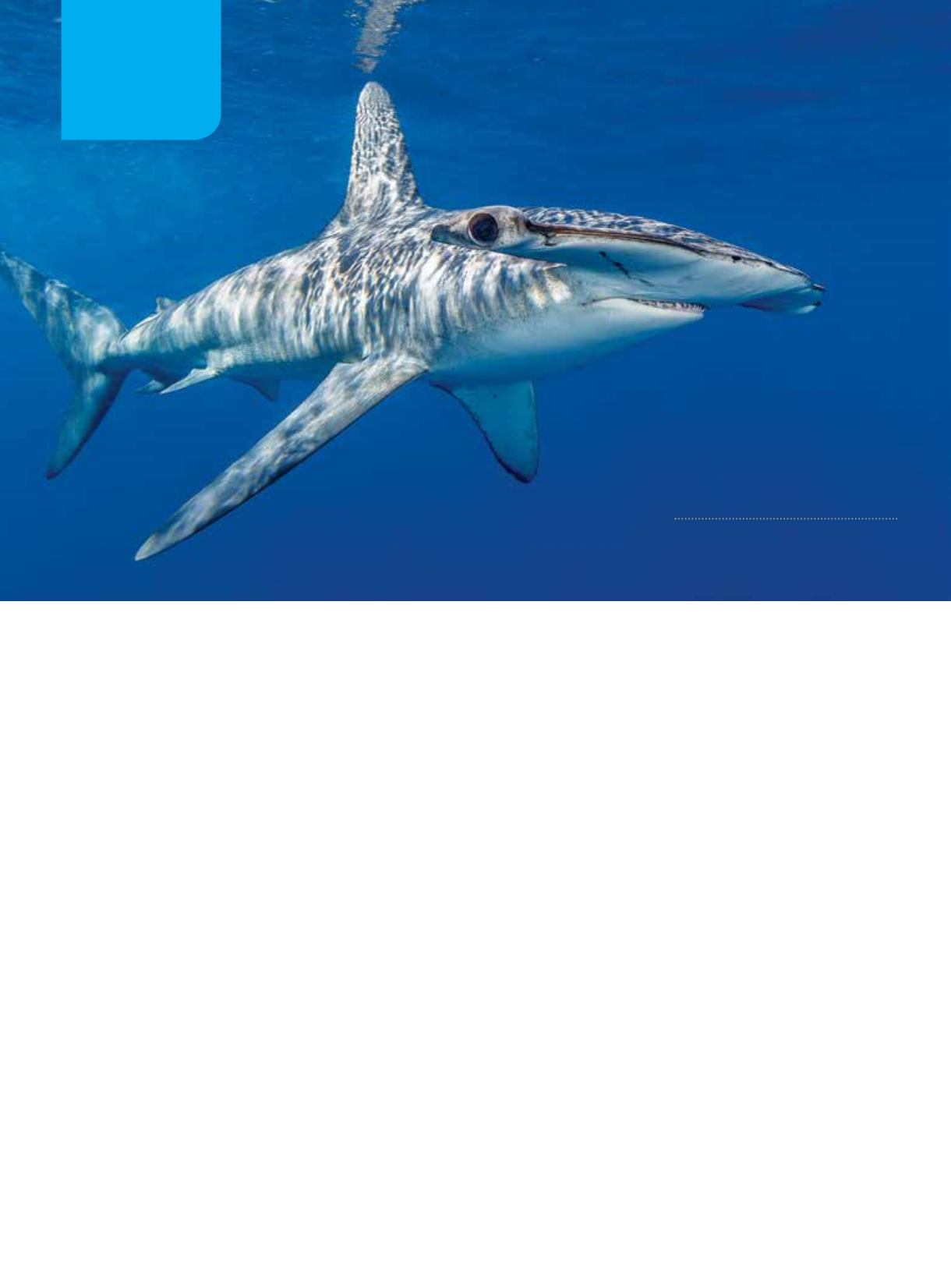

E

very California diver I know has a

recent story about when they first

noticed things were changing at our

local dive sites. Some recall their local

kelp bed looking thin, while others

mention the presence of yellowfin

tuna on every shore dive, the range extension of a

Mexican nudibranch or the appearance of a skinny

baby sea lion on the swim step of their dive boat. For

me it was when a 9-foot-long smooth hammerhead

shark curiously bumped my camera rig. It was August

2014, and it was no secret that the surface waters were

a few degrees warmer than normal.

On that day the swell and wind were formidable,

but we were determined to get offshore. We hoped to

get a good look at the hammerhead sharks — typically

a subtropical species — that had been spotted at the

surface by one or two multiday dive boats over the

past few weeks. We couldn’t believe our luck when

one showed up and interacted closely (at times, very

closely) with us for three hours.

Among divers the rumored cause for the oddities

of the summer of 2014 was El Niño

(the warm phase

of the El Niño Southern Oscillation), an ocean-

atmosphere interaction in the east-central equatorial

Pacific that strongly influences ocean conditions

and weather patterns. However, the U.S. National

Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration (NOAA)

had not confirmed the presence of El Niño

conditions.

Meanwhile, Washington state climatologist Nick Bond

had already come up with an alternate name for the

odd patch of warmer-than-usual ocean off the coast of

the Pacific Northwest: “The Blob.” This phenomenon,

thought to be the result of locally persistent high

pressure that inhibited normal wind-driven oceanic

upwelling and cooling, had spread along the West Coast

and encompassed multiple stretches of ocean from

Alaska to Mexico.

In some places the ocean’s surface was 5°F warmer

than usual. Although the Blob quickly replaced El Niño

as the established cause, 2014 diving and fishing reports

in Southern California confirmed the effects, each more

bizarre than the last. Tuna fishermen came back from a

day offshore east of Catalina Island with images of a whale

shark. The lush, iconic kelp of Catalina and San Clemente

islands dwindled, and in some places this enabled prolific

growth of

Sargassum horneri

, an invasive alga that better

tolerates warmer water. A GoPro video of a manta ray,

106

|

WINTER 2016

WATER

PLANET

A PERFECT STORM OF WARM

Text by Allison Vitsky Sallmon, DVM; photos by Andy and Allison Sallmon

Unusually warm surface waters in

California have made it easier to

interact with uncommon creatures, such

as smooth hammerhead sharks.