gracefully flapping among sparse kelp stalks, created a

fanatical rush on local dive charters.

By the time NOAA confirmed the arrival of El Niño

conditions in March 2015, it was hard to believe that

things could get any stranger, but they did. Sea bird

and California sea lion populations began experiencing

devastating die-offs. In April 2015, strong west-to-east

surface winds blew masses of violet-blue

Velella velella

,

open-ocean hydrozoans related to jellyfish, onto

beaches in California, Oregon and Washington. And in

June 2015 I watched in amazement as pelagic red tuna

crabs (a squat lobster-like crustacean normally found

near central Baja California) swarmed one of our few

remaining local kelp beds and ultimately littered the

coastline from San Diego to Los Angeles.

The peculiarities didn’t stop there. In July and August

2015, smooth hammerhead sharks were bumping near-

shore kayak fishermen so commonly and assertively that

local beaches were closed on multiple occasions. On

the docks, anglers posed proudly next to bluefin tuna,

caught only 10 miles offshore, and local photographs of

finescale triggerfish and Guadalupe cardinalfish became

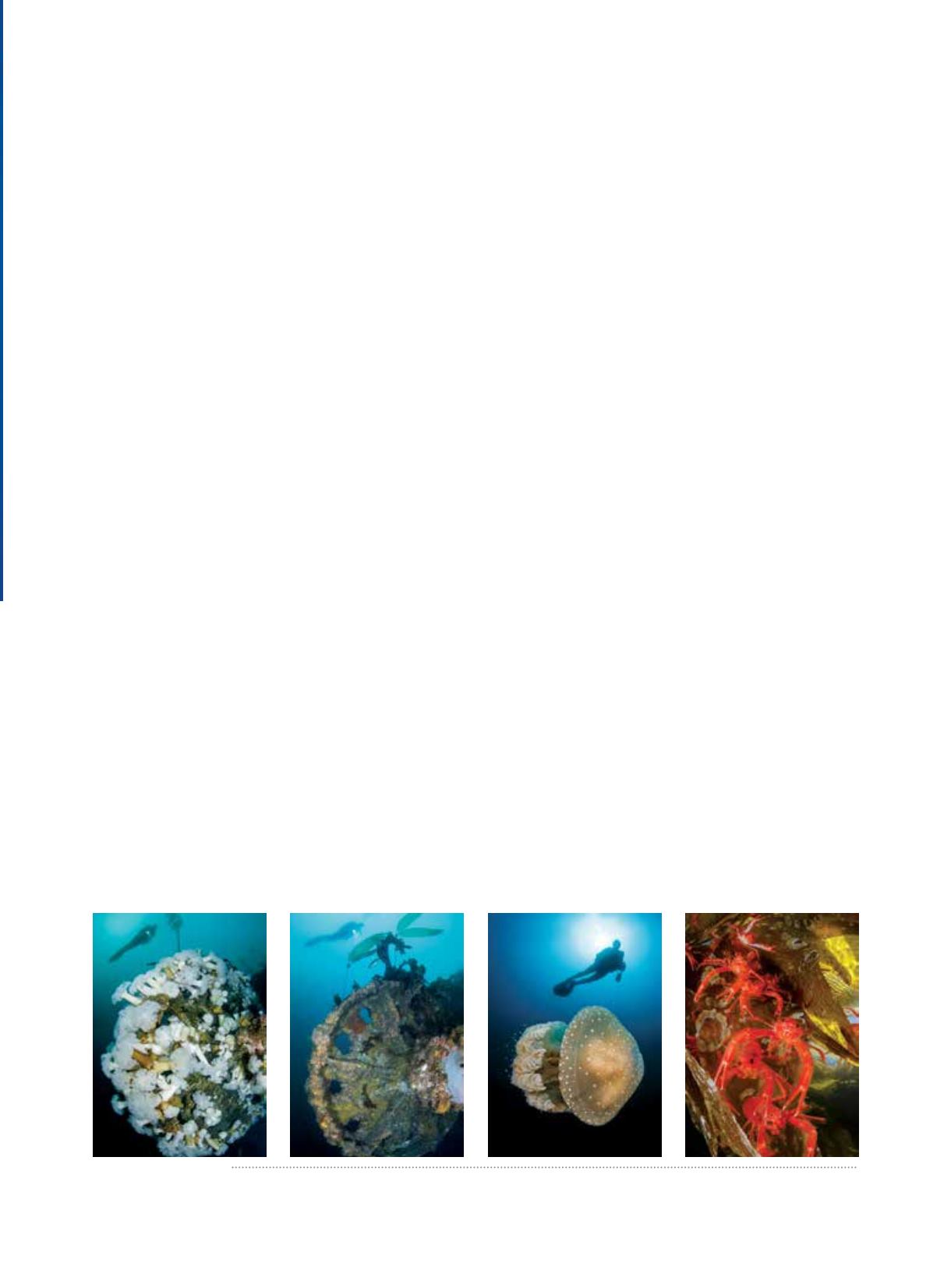

commonplace. In September 2015, I hovered in disbelief

next to the barren propeller of the HMCS

Yukon

, a

San Diego-area artificial reef that had been thickly

encrusted with giant plumose anemones only 12 months

prior. And only a month after that, a cluster of wahoo

passed me at a Catalina Island dive site days before I

photographed a pulsing Australian spotted jellyfish

near the San Diego harbor. The world — at least, the

underwater world I frequented on a regular basis —

seemed to have gone stark raving mad.

Ed Parnell, Ph.D., research oceanographer at the

Scripps Institution of Oceanography, wasn’t terribly

surprised to hear it. “The Blob was an unprecedented

warm-water event that wasn’t related to common

oceanic indices,” he explained. “Last year we had warmer

surface conditions, but at depth things remained cold

and nutrient-rich, so some deeper species were less

affected than you might think. However, the water

became very stratified and more resistant to mixing.

Typically, an El Niño pattern results in advection of

pulses of warm equatorial water northward, so that

upwelled water is warmer than normal and less able

to deliver nutrients to shallower structures. But this

year, with things prestressed by the Blob, the seasonal

thermocline is already deeper than normal, so upwelled

water would likely be even warmer than we’ve seen with

prior El Niños — in fact, this year upwelling might not

deliver much cold, nutrient-rich water at all.”

Parnell’s key concern is further overgrowth of

invasive

Sargassum horneri

. “Two years ago, we were

seeing isolated pockets of it, but now it’s popping up

everywhere,” he said. “If we lose the kelp in an area

completely, sargassum can easily take over because it

will no longer be suppressed by giant kelp shading.”

Previous El Niño

events have delivered mighty topside

changes to the West Coast as well. In the past, the

position of the jet stream has shifted south and east

from the Gulf of Alaska so that storms track closer to

the Southern California shoreline. The strong El Nino in

1982-83 brought crippling storm fronts, complete with

waves that broke over the roofs of popular beachside

restaurants. And in 1997-98, repeated deluges washed

away roads and caused catastrophic mudslides. With

California in the midst of a drought, it feels a little

ungrateful to admit that stories of the past combined

with ever-more-ominous nicknames bestowed upon the

present El Niño

(“Bruce Lee” is my current favorite) are

more than a little frightening.

Parnell, however, says this may be one of the biggest

reasons to remain optimistic. “Strong storms can

revamp the bottom structure, remove urchin barrens

and clear out the understory kelps, providing renewed

areas for giant kelp to grow,” he said. “El Niño may bring

a series of storms, but we need to remember that those

large storms act as a reset button for kelp forests in

Southern California.”

AD

ALERTDIVER.COM|

107

From left:

The propeller of the HCMS

Yukon

wreck in San Diego’s Wreck Alley was thickly covered with giant

plumose anemones in spring 2014. By the summer of 2015, the ocean had become warm enough to wipe

them out, leaving nearly bare metal behind. A diver pauses over an Australian spotted jellyfish near the coast

of San Diego. Pelagic red tuna crabs, a denizen of Baja, Mexico, swarmed a California kelp bed in June 2015.